The following post was researched and authored by Emily Riippa, Assistant Archivist.

For most Americans of today, the word “tuberculosis” carries little weight. It might mean a needle prick to the forearm before being approved for a hospital volunteer position or a warning offered to vacationers bound for China, Brazil, or Kenya, three of the countries where the disease maintains a foothold. Those living in the United States now might forget a time in this country when tuberculosis (TB) was a dreaded scourge called the “white death.”

In those days, the Copper Country was at the epicenter of Michigan’s tuberculosis problem. By 1930, the death rate among those suffering from the disease was higher in Houghton and Keweenaw counties than anywhere else in the state and nearly double the statewide average: 117 deaths per 100,000 people in these two counties, according to data collected by contemporary public health officials, compared to 60 deaths per 100,000 statewide. Dr. James Acocks, a physician who spent most of his career treating TB patients in the Upper Peninsula, recalled that public health officials advanced many potential explanations for the apparent epidemic in mining country but never definitively determined its cause.

Even if the origin of the plague remained a mystery, the need for tuberculosis care in the Keweenaw was plainly apparent. In 1910, Houghton County voters approved a bond measure to construct a sanatorium on a plot of civic land near Houghton Canal Road, not far from the county’s residential facility for the indigent. In keeping with the prevailing treatment philosophies of the time, which called for ample fresh air and natural light, the wood-frame building of the Houghton County Sanatorium featured a large screen porch to which patients were escorted on days when the weather was nice. The sanatorium was intended to house just twelve people at first, but the large local TB population quickly overwhelmed this small capacity, even with assistance from outpatient clinics. In 1915, the sanatorium was enlarged to house thirty-six patients; a second expansion two decades later added another twenty-nine beds–removing the much-heralded screen porch–and a 1940 WPA grant allowed for various other upgrades to the facility, now called the Copper Country Sanatorium. Just a few years after the WPA improvements, however, a state inspection found the tuberculosis hospital to be “an obvious fire trap” and unfit for continued use. Construction began soon after on a modern brick building in Hancock, not far from what was then St. Joseph’s Hospital; the new facility would open in 1950.

These twilight years of tuberculosis treatment at the Houghton Canal Road building, however, yielded a truly rare gem, one recently donated to the Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections. In 1950–the last year the original sanatorium operated–a resident patient apparently smuggled a camera into the hospital and captured snapshots of experiences there. Thirty-three of those photographs are now part of MS-963: Brenda Papke Photograph Collection, a newly-processed collection just made available for research. The images are a look behind the scenes, so to speak: a unique and sometimes furtive glimpse into the lives of people whose fight against a devastating, deadly illness had taken them away from home and family.

Although no information about the individual who took the sanatorium pictures has come down to us, it seems likely that the photographer was a woman. Many of the images depict women lounging in what appears to be a female ward of the sanatorium. Seemingly relaxed and content, for one photograph the ladies propped their legs on the bedside tables, rolled up their pajamas or bathrobes, and flashed views of their ankles and thighs that vaguely remind the viewer of 1940s pinups. For another picture, two women hopped into bed beside an open window and threw their arms around each other, beaming out at the camera in a manner that seems almost carefree. One of the women had decorated the area above her bed with a calendar, an image of a puppy and a kitten, an advertisement with a child’s picture, and two wishbones–presumably for good luck in the face of tuberculosis. In several other images, a large contingent of female patients assembled for a group shot, all dressed in their best bathrobes or house dresses and with hair neatly curled. Tall women, short women, women whose wrinkled faces testified to many years already lived, women whose youthful appearance bespoke a hope that their whole lives still lay ahead of them–vastly different women all, part of a sisterhood forged by the scourge of tuberculosis.

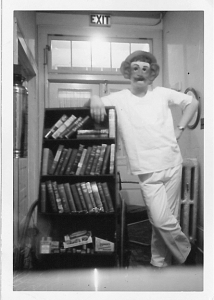

While many of the pictures show female camaraderie in the sanatorium wards, other images show the mingling and mixing that took place across the hospital. The photographer captured two men hard at work at some sort of machine, perhaps a kitchen tool or a shop instrument. Another young man was apparently a favorite model, repeatedly striking dramatic poses inside and outside the building while wearing his monogrammed pajamas. The women who had been pictured relaxing in bed crowded onto a bench with their male counterparts, squinting against the light of the sun as the photographer captured a group shot. In other cases, sanatorium staff got in on the action: the collection includes two pictures of nurses, both candid and posed. Then there were moments of pure absurdity, with one individual donning an outrageous mask and pushing a bookshelf in a wheelchair through the hallway. Despite the serious threat of tuberculosis hanging over their heads, fellowship and fun obviously persisted among the sanatorium’s residents.

The Brenda Papke Photograph Collection is a trove of visual treasures, of which the photographs presented in this piece are only a part. The thirty-three sanatorium pictures truly take the researcher into the heart of the hospital, helping one to glimpse what life was like for those who found themselves on the front lines of the fight against tuberculosis. Interested in investigating the collection for yourself or finding out more about the treatment of TB in the Copper Country? Feel free to stop by the Michigan Tech Archives during our normal business hours, give us a call at (906) 487-2505, or e-mail us at copper@mtu.edu.

Fascinating! Great insight into what these patients experienced with a disease that was frightening and isolating. An interesting look at a difficult time–well researched and superbly written.

Thank you for reading our blog! We are very happy to have Emily as a colleague. She has made great contributions of research and writing to improve our blog content. Thanks again for being in touch and have a great day!