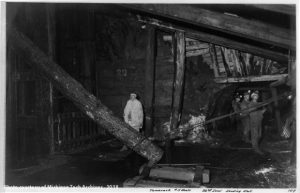

Tamarack No. 2 shaft buildings pictured in 1892.

An employee walking to work at the Tamarack mine in early October 1901 would have seen the same landscape he saw every day: smokestacks coughing fumes into the air, mighty logs waiting to be hewed into shaft timbers, tall industrial structures silhouetted against the autumn sky. Everything would have seemed normal to him, the prelude to another regular day. Yet the Tamarack was not an ordinary place, and joining the employee at work that day were several men about to do something especially unusual, something that would raise eyebrows for years to come.

The Calumet & Hecla Mining Company (C&H) had already proven the richness of the Calumet conglomerate lode when the Tamarack Mining Company was organized in 1882. Hamstringed by C&H’s property holdings, other mining investors desperately spent years seeking some way to tap into the lode and the profits. Time after time, they fell short. Then, finally, one had an epiphany. John Daniell was the superintendent of the competing Osceola Mine and a crafty mining engineer, and the plan he devised was entirely in keeping with his line of thinking. Daniell knew that copper lodes did not follow strictly vertical paths.

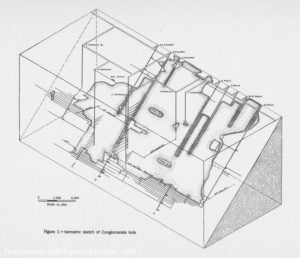

Rather, they ran under the earth’s surface at angles. C&H might own the land with the easiest–and most economical–access to the Calumet conglomerate lode, but their holdings couldn’t possibly cover the whole deposit, especially thousands of feet underground. With the cooperation of some notable investors, particularly Joseph W. Clark and A.S. Bigelow, Daniell and the Tamarack Mining Company drove five deep shafts at the very western reach of C&H property. Eventually, they hit copper–and paydirt. The Tamarack lands proved to be remarkably profitable, and the mine flourished.

Daniell’s strategy of plunging deep into the earth was also precisely what allowed the Tamarack to become a massive laboratory. In October 1901, scientists and engineers from the company and from a certain local mining school gathered to study magnetic attraction, gravitational forces, and the behavior of pendulums underground. The Tamarack mine shafts afforded them an unprecedented opportunity. How often, after all, did an experimenter have the chance to work with a plumb line over 4,200 feet long? Since the employees of the mine had already done the dirty, backbreaking work of excavating nearly a mile into the earth, the shafts could serve a dual purpose.

To keep the description succinct, in short the experimenters expected that two plumb lines suspended in a mine shaft would be nearer to each other at the bottom of the line than at the surface. The earth is convex (curved on the exterior), so the plumb lines would be drawn together as they descended toward the core, allowing a precise calculation of the angle the planet’s convexity caused convergence. If that line confused you, don’t worry; that’s as technical as today’s Flashback Friday gets. If that line left you wanting a better and more scientific explanation, head over to a post that Donald Simanek, an emeritus professor at Lock Haven University in Pennsylvania, wrote to analyze the physics and mathematics in greater depth.

Carefully, the engineers present at the Tamarack that October day selected and tested what the Daily Mining Gazette at the time described as “No. 24 piano wire” for their experiment. Once the wire met with everyone’s approval, “it was necessary, of course, that each wire have something attached to it to carry it down. It was not thought best, however, that common weights be used, as it was feared they would in some manner get caught in the timbering [of the mine] and ruin the whole experiment.”

Instead, the men fashioned two “balloons… each ten feet long and built entirely of wood… they were two and one-half feet in diameter at the centre, tapering to a point at either end.” Balloons and piano wire descended together into the No. 2 shaft. When they reached the designated stopping point at the 29th level, the balloons were replaced with “50-pound cast iron bobs… then immersed in engine oil in order to kill all the vibration possible.” Now, data could be collected.

The wires had, thanks to the changes in weight as the bobs were replaced and the buoyancy of the engine oil, underground various fluctuations in length. The scientists found these normal, natural, and anticipated. Measuring the distance between the two bobs in the shaft proved more interesting. They hadn’t converged at all. On the contrary, the bobs of the two plumb lines sat 0.07 feet farther from each other than the tops of the lines to which they were attached.

What could have caused the strange result? No doubt, experimenters felt excited by this point. To the layperson, 0.07 feet of divergence might seem insignificant; to an engineer expecting the opposite outcome, it was an interesting problem. Later observers would propose a variety of potential solutions: variations in the density of the crust, buoyancy of the oil, geometric quirks, gravitational effects, or mere misinterpretation. Professor Simanek laid out all of them in turn in the aforementioned Lock Haven article, and those wanting to dig into the nitty gritty may enjoy his piece. Suffice to say, however, it took more than casual spitballing over a few cups of coffee to narrow down the cause.

More interesting, perhaps, to the casual Flashback Friday reader is the way in which the Tamarack mine found itself catapulted into conspiracy theories and weird science. After all, mused some, couldn’t the failure of the plumb bobs to converge mean that there was nothing attracting them in the first place? Perhaps the earth was actually hollow. Maybe, instead of being convex, it was actually concave, curving inward beneath the surface. Surely the Tamarack experiment had shown that more was afoot than met the eye.

Of course, in Houghton County in the peak of the mining boom, there was always more going on underground than met the eye. Imagine the thousands of men roaming the shafts day in and day out, carrying tools and lights and conversing in dozens of languages, meeting those just trying to haul rock and those trying to calculate the convexity of the earth. Perhaps the crossroads of the world were not above it at all but instead a mile below its surface.

A remarkable story! As a native of the Copper Country I had never heard of this. It is an interesting piece of history that surely cannot be repeated only, analyzed.The writer has done an amazing job of laying this complex story out so that in can be understood.Hooray for MTU Archives. Thank You Flashback Friday for the truly fascinating story!!! Bravo!!

Excellent article! I always enjoy knowing “the rest of the story” and this one does not disappoint. Well told and fascinating. I look forward to more of your “Flashback Friday” stories.

Excellent article! I always enjoy knowing “the rest of the story” and this one does not disappoint. Well told and fascinating. I look forward to more of your “Flashback Friday” stories.