April 11, 1869 was a Sunday. Many residents of Hancock woke up and went about their regular routines in the early dawn hours: cooking breakfast, dressing for church, wishing for a little more sleep. Who could have suspected that normal life was about to take a long hiatus?

Others in the flourishing little village hadn’t gone to bed yet. They had spent the time from Saturday night into Sunday morning dancing at a saloon just a stone’s throw from St. Anne’s Catholic Church, on the north side of Hancock. As the rambunctious party broke up that morning, it seems that someone knocked over the stove whose glowing warmth had kept the dancers cozy through the long night. The burning fuel spread across the floor of the bar. “Without attempting to extinguish the flames which at once sprung up,” wrote the Portage Lake Mining Gazette in an article republished by the New York Times, “the party decamped and left the building to its fate.”

The loss of the saloon would have been tragedy enough for its proprietors. Unfortunately, a minor catastrophe quickly escalated into a major disaster. As with most newborn mining settlements, Hancock’s buildings had primarily been constructed from wood. Worse yet, the wind was blowing from the northwest, swiftly fanning the fire east and south into the heart of town. “In less than half an hour,” wrote the Gazette, “there were half a dozen buildings in flames” on the saloon’s side of the street, “and soon those on the other side caught from the intense heat, and burst out with unexampled fierceness.” In modern firefighting parlance, Hancock had flashed over, a particularly vivid and appropriate term for the rapid spread.

Hancock had prepared to fight a fire, but its people had not anticipated a blaze on this scale. The town had a modest water reserve (Portage Lake was frozen) and an even humbler municipal firefighting apparatus, underwhelming even by the technology of the time. Within half an hour, the water had run out without abating the flames that had already engulfed at least thirty-five structures. The fire continued to spread, forcing inhabitants to flee as it consumed building after building. “The air was hot, suffocating, and thick with blinding smoke–now settling down like a pall over the whole town,” explained the Gazette in an attempt to recreate the horror of the scene. When the winds did lift the smoke a bit, the frightened refugees glimpsed “broad sheets of flame from fifty to five hundred feet in length, and reaching, at times, almost the clouds.” No one whose home or business stood in the way of the blaze entertained any hope that the buildings would be saved. Instead, they banded together to try to rescue the contents. Store owners “tumbled their stocks pell-mell into the streets, and hundreds of willing hands conveyed them speedily, if not very tenderly, beyond the apparent danger.” As the fire’s path became even more ambitious, even the safe places where these goods had been taken had to be evacuated.

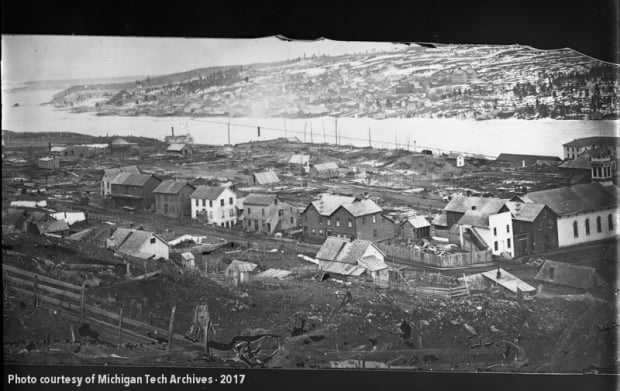

About six hours after they had broken out, the hungry flames found no fuel left for them to consume, and the roar of the blaze slowly died down to quiet smoldering. “Nearly all that remained of the once thrifty village of Hancock was an immense heap of embers, covered with a stifling cloud of smoke,” said the Gazette. Some modest buildings formed “a small fringe” along the northwest part of town, where the fire had started; two churches (St. Anne’s and the Methodist congregation) and two public halls that still stood among the ashes must have seemed towering by comparison. Among the estimated twelve acres scorched were some 130 houses and “every store in the town.” Rebuilding would be a massive process.

One cannot help but see parallels between the Hancock fire of 1869 and the flash flood of 2018 in the community’s responses to each. “The people seem to have accepted the situation, and have gone to work with a will,” the Gazette explained in 1869. Their words might as well have been written in 2018. Within a matter of days, Hancock residents and their neighbors had erected the beginnings of more than two dozen temporary structures where the burned ones had stood. Photographs taken of Tezcuco Street later in the year showed a maze of new buildings and framework lining each side of the road; piles of lumber in the middle of the route stood ready to finish the work. Although those who had lost homes and businesses no doubt suffered and continued to struggle, they also fixed their eyes on the path ahead and let their persistence carry them through. Neighbor helped neighbor; friend reached out to friend. Slowly, the normalcy that had existed in the early morning of April 11, 1869 returned.

Today, Hancock bears little resemblance to either the town that existed before the great fire nor the town that rose, phoenix-like, from the ashes in its immediate wake. Survivors of Hancock in its pre-1869 infancy remain, however. Along Hancock Street (the southbound portion of US-41 in town) sit the O’Neill-Dennis Funeral Home and a residence bearing a “CELTIC HOUSE” plaque. As the parsonage of the Congregational Church in Hancock and the residence of Dr. W.W. Perry, respectively, both endured the fire and testify to the endurance of the city. The municipal government also makes available the New York Times reprint of the chronicle of the blaze. These, along with archival materials and books available at the Michigan Tech Archives, tell the story of a town that won’t go down without a fight.

Want to know more about the fire of 1869? John S. Haeussler’s 2014 book “Images of America: Hancock” provides the most complete collection of photographs showing the before and after, as well as detailed captions that helped to inform this blog post.

It is amazing that such a devastating fire could be forgotten through the ages! While maybe not as large as the Chicago fire it was just as harmful to the lives of Hancock residents as the Chicago fire was to residents of the “windy” Thank You MTU archives for making sure this event is remembered. Kiitos!!