Writers and other storytellers have envisioned murders for profit, murders committed in a fit of passion, murders resulting from some deep-seated flaw of character. Then there are those murders so strange that even twisted minds could not have imagined them. This is one of those crimes.

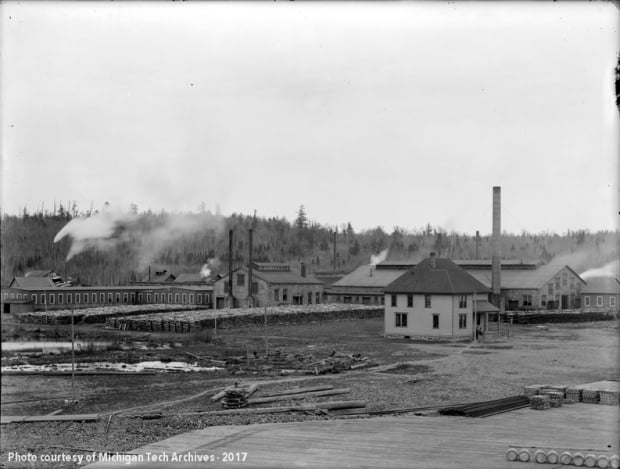

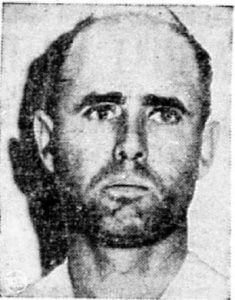

Imagine the Copper Country in 1938. The mining industry was no longer thriving and vibrant in the way it had been at the turn of the century. Plummeting copper prices after World War I led companies to suspend operations at some of their shafts and curtail their workforce, a problem exacerbated by the Great Depression. As many would-be workers left to find jobs elsewhere, the population of Houghton County declined from a little over 71,000 people in 1920 to 47,631 in 1940. In this environment, envision now a man named Wilfred Pichette. Born in Dollar Bay in 1899, he spent almost all of his life in Michigan. As a younger man, Pichette had followed in the footsteps of thousands of his Houghton County peers and sought employment at Calumet & Hecla, where he was assigned to the stamp mill of its Isle Royale Copper Company branch. In 1924, Pichette married seventeen-year-old Laura Bourassa (or Brassaw), also a Dollar Bay native and the second major part of the story. The two set up housekeeping in their hometown, remaining close to Laura’s parents, and soon had a son, whom they also named Wilfred. While the copper industry remained capricious, life in the Pichette house must have seemed normal and promising for a time.

It wasn’t long, however, until the Pichette family began a downward spiral, the product of chance, tragedy, and, in part, their own choices. Calamity claimed little Wilfred, Jr., first. In February 1930, he was hit by a car and rushed to St. Joseph Hospital in Hancock, where he soon succumbed to his injuries. As the Depression brought a deeper downturn in the copper market, Calumet & Hecla laid off numerous employees, including Wilfred, Sr. Although he later found a Works Progress Administration (WPA) job, the period of unemployment no doubt shook the Pichettes. In 1931, they had another child, a daughter named Norma Betty; blessedly, she remained healthy and safe. Sadly, their second daughter, Winifred, died in 1935 at the University of Michigan Hospital. Complications from meningitis took her life just five months after her birth.

Whether these challenges pushed Wilfred and Laura Pichette to the brink or whether unstable personalities and a troubled marriage already existed cannot be said with certainty. But the descent into tragedy only accelerated when, in April 1938, Laura left Dollar Bay. She and a man who had rented a room from her, Russell Cassidy, traveled to Newberry together. There, they found a home and began living “as husband and wife,” in the euphemistic words of subsequent court documents.

In his wife’s absence, Wilfred proved to be entirely unprepared to take care of the Dollar Bay house and his little daughter. At the urging of his exasperated mother-in-law, he sought a housekeeper, eventually hiring a young woman from Hancock named Marian Doyle to move into the Pichette home. Wilfred knew what Laura and Russell were doing in Newberry and may have decided that turnabout was fair play. In short order, housekeeper and employer began their own affair, and Marian soon informed Wilfred that she was pregnant.

An out-of-wedlock pregnancy in the 1930s would have been difficult enough for all involved, but what began as a crisis in the Pichette household rapidly unraveled into catastrophe and crime that went far beyond those four walls. In October, Laura Pichette abruptly returned to Dollar Bay from Newberry. Her relationship with Russell Cassidy had come to a sudden end. The atmosphere in the house immediately grew awkward, ominous, foreboding as the estranged Pichettes contended with each other and with the presence of the housekeeper. Laura came home on a Wednesday. By Saturday, Marian Doyle was dead.

No one outside the house knew what had happened until Mary Marcotte, Laura’s mother, walked to the nearby Pichette house on Sunday, October 23. Mary would later testify that Laura, Wilfred, and their little girl all met her at the door. Laura blurted, “We killed Marian Doyle.” Terrified into excitement, little Norma Betty repeated Laura’s words, her child’s voice telling a story that none ever should. Mary screamed and ran for home, with Wilfred hot on her heels. He urged his mother-in-law to go to the second floor of his house and see the evidence for herself. When she resisted, he retreated. Soon, someone telephoned the sheriff’s office with news of the murder. Dollar Bay’s idyllic autumn morning had been shattered.

Deputies Ernest “Ike” Klingbeil and Matt Verbanac arrived on the scene shortly after noon and knocked at the back door. Wilfred Pichette answered it and, after frankly and intensely confessing to the killing, marched the two deputies up the stairs to Marian’s bedroom. The scene was gruesome to behold. “The body was cold,” Klingbeil said at the trial. “Her eyes were black and blue. There was blood spread all over her face, hands.” Klingbeil and Verbanac also noted blood on the bed and on the wall. By this time, Wilfred Pichette had fallen silent. He would make no further statements to the deputies as long as they stayed at the house.

After they had taken in Marian’s grisly remains and the bloodshed in the bedroom, Klingbeil and Verbanac investigated the remainder of the house. Verbanac testified that they found drops of blood leading down the stairs and all the way into the kitchen. Splattered on the wall, chair, cellar door, and floor in the otherwise clean kitchen was even more blood, and the deputies discovered matching stains on a heavy flat iron. A stove poker showed signs of having been hastily washed. With Marian’s body, Wilfred’s frank admission at the door, and the apparent murder weapons at hand, Klingbeil and Verbanac knew immediately what had to be done. They bundled the Pichettes into their squad car and headed for the county jail in Houghton.

On the journey to the jail, husband and wife denied any knowledge of Marian’s death and proclaimed their innocence. Everything had been just fine in the Dollar Bay house the night before. With Norma Betty tucked in bed, the adults had sat up listening to the radio and “having a good time” before retiring. When Wilfred and Laura rose the next morning, they found Marian’s battered, bloody corpse, just the way the deputies had seen it. Someone else must have killed her while they slept and fled the house.

The policemen kept driving.

Prosecuting Attorney Frank Condon, one of his assistants, and a stenographer were called to the jail shortly thereafter; County Coroner Dr. Addison Aldrich was dispatched to examine the body. Under the keen questioning of the deputies and lawyers, the Pichettes’ claims of ignorance eroded. Wilfred began by saying again that he knew nothing. Eventually, as the lawyers pressed him, he conceded that he owned the stove poker and flat iron that had been used to beat Marian to death. The prosecutors pounced. How many times had Wilfred struck Marian with the flat iron? Several times, he admitted grimly. The stenographer’s pen scratched across the page.

Laura Pichette was easier to crack. She stated outright and with little coaxing that she and her husband had killed Marian Doyle together. Wilfred had taken up the flat iron and begun the brutal beating; later, Laura seized the stove poker and joined him, striking the housekeeper ten times. She insisted that she had done so only at his request. The fact remained, however, that both Wilfred and Laura had admitted that they “did strike, beat, bruise, wound and ill-treat the said Marian Doyle in and about the head, neck, and body,” leading to her death.

The police and the prosecutors now had two confessed murderers in their custody, murderers who would soon be brought before the court to plead their case. Marian Doyle’s body lay under examination by the coroner, who had the thankless task of determining which of her numerous injuries had been the fatal one. The local newspaper would not be long in picking up on the story, especially when Wilfred and Laura’s stated reasons for killing Marian Doyle were made public.

She was a witch, they said. She had been “full of devils,” and her death had cleansed the house of “evil spirits.”

The death of Marian Doyle–what the papers called the Witch Murder, the Spirit Slaying–became a circus that drew crowds to wait in the street outside the courthouse and shone a spotlight on quiet Dollar Bay. The story grew only more sensational as witnesses came to the court and as the accused appeared before the judge to make their statements. What happened next seemed to have been taken straight from a soap opera or crime drama, but it was all entirely true.

Next week’s sequel to this Flashback Friday will address the trial and aftermath of the crime. Sensationalism, tragedy, and mystery lie ahead. Be sure to come back and learn how the story ends.

Thank you for posting this. I am related to the Pinchettes and I remember my mother telling me about this.

Very interesting……

My dad Roger Backman was working at the Dollar Bay gas station then. He was only 19. He said Wilfred came there and said he just killed the devil. Dad probably thought he was just a little bit off and dismissed it. The rest is history.

Only the shadow knows what evil lurks in the minds of men (and women) haaa haaa haaa!

A majorly interesting story about something so unthinkable! Thank You to the writer for bringing history to life….so to speak

What an intriguing story and well told. I would not have expected that of such a bucolic area of the Copper Country. I can’t wait to hear “the rest of the story”.