The press called Maggie and Bill recluses and hermits, not people.

At different times, in different parts of Keweenaw County, Maggie Harrington and Bill Mattila chose lives of solitude. Maggie kept her home in Central Mine as that community faded and her neighbors moved away. Nearly thirty years later, Bill climbed Brockway Mountain to build his dwelling. Outsiders fixed them with curious stares and peppered them with questions about their lives, their choices. Some, Maggie and Bill answered; others, they left as mysteries. Both died in the remote places they had called home just the way they lived–alone but not necessarily unhappy.

There’s much about the lives of these two people–who attracted so much fascination for their unorthodox decisions–that remains unknown. Stories swirled in their wake, built on what the two had decided to share and on the inventions of others. Bill, for one, often told reporters and visitors what they wanted to hear, not necessarily the truth of his life. But what can we say about these two people to give their legends some roots?

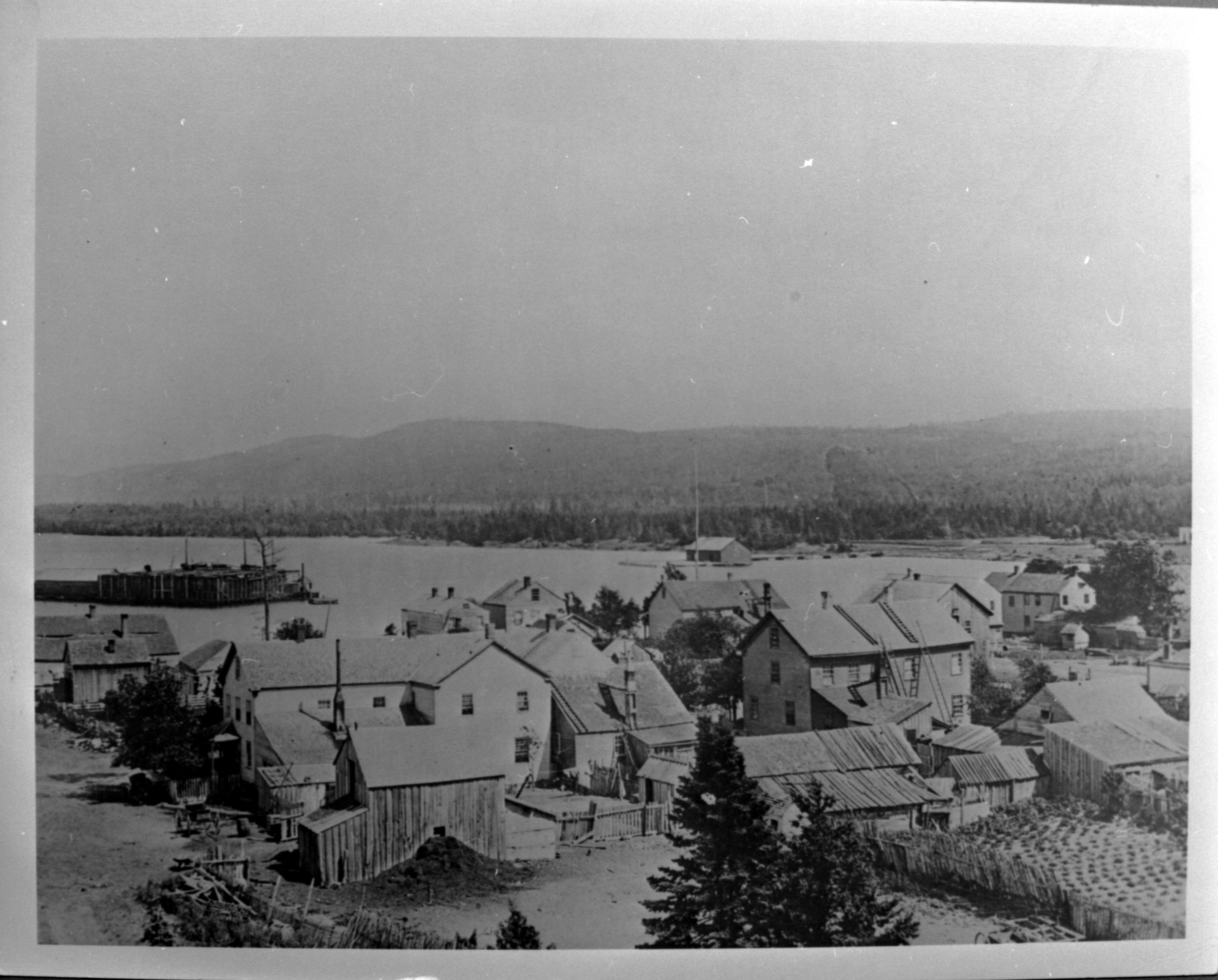

Maggie Harrington was not famous in life and remains so in death, but everyone who clung to life in Central after the mine closed would have known her. Census records tell us that young Margaret Harrington and her mother of the same name, both immigrants from Ireland, had established themselves in Keweenaw County by 1870. At that time, their residence was near the Pennsylvania Mine, an area that today’s visitors would call Delaware. By 1880, they had moved down to the more prosperous Central Mine, settling on the east edge of town. Maggie was sixteen at the time. As at Delaware, she and her mother lived alone; another group of Harringtons resided a few doors down, but Maggie and Margaret formed their own household. Whether the older Margaret Harrington had ever been married or had other children is not clear. Maggie’s obituary alluded to a sister, name not given, who had wed a Mr. Michael Powers. A miner by that name did reside at Central as of 1863, when he was registered for the Civil War draft, and a peddler named Michael Powers died in Eagle Harbor in January 1871, but whether either was connected with the Harringtons remains a mystery.

In September 1896, the older Margaret Harrington died at Central Mine. The town itself was fading, too. People whom Maggie would have known since childhood moved away, seeking work in the mines of Calumet, Hancock, or points farther west. A few people who had always called Central home remained, and Maggie was determined not to leave. With her mother gone, she spent much of her time alone with her thoughts. Daily, she walked the forested paths of Keweenaw County, journeying down the steep hill that led to Eagle Harbor or cutting across the woods to Eagle River. The weather did not deter a woman who had known so many Copper Country winters. When it snowed, she wrapped herself more tightly in her coat and scarf and tucked her feet firmly into her boots. Anyone who would live by herself in a town as quiet as Central had to have courage.

And yes, people peered at Maggie, asked questions about her, whispered stories about her behind their hands. When they saw her walking along the road, motorists pulled over and offered her a ride. Sometimes, no doubt, it was out of courtesy; sometimes, it had to be curiosity. The Daily Mining Gazette said that she always immediately refused unless she knew the person; when she did accept, she seemed reluctant to agree and even more reluctant to carry on a conversation. She chose to keep her own company and to go her own way. When she died, these decisions became the cornerstone of her obituary.

One of Maggie’s long walks became her last walk in 1926. Others who normally saw her journeying about the woods or tromping past their windows noticed that the familiar figure hadn’t appeared for some days. A man who had stayed on at Central as a caretaker for the mine buildings organized a search party that eventually found Maggie’s body in a snowbank. She had apparently taken her normal long walk down to Eagle Harbor and detoured through Phoenix on her way home. For reasons unknown, as she approached Central, she changed her mind and began to walk back toward Phoenix. She passed away along the route. Later, her neighbors bore her down the state highway she had so often traversed and laid her to rest in a Catholic service.

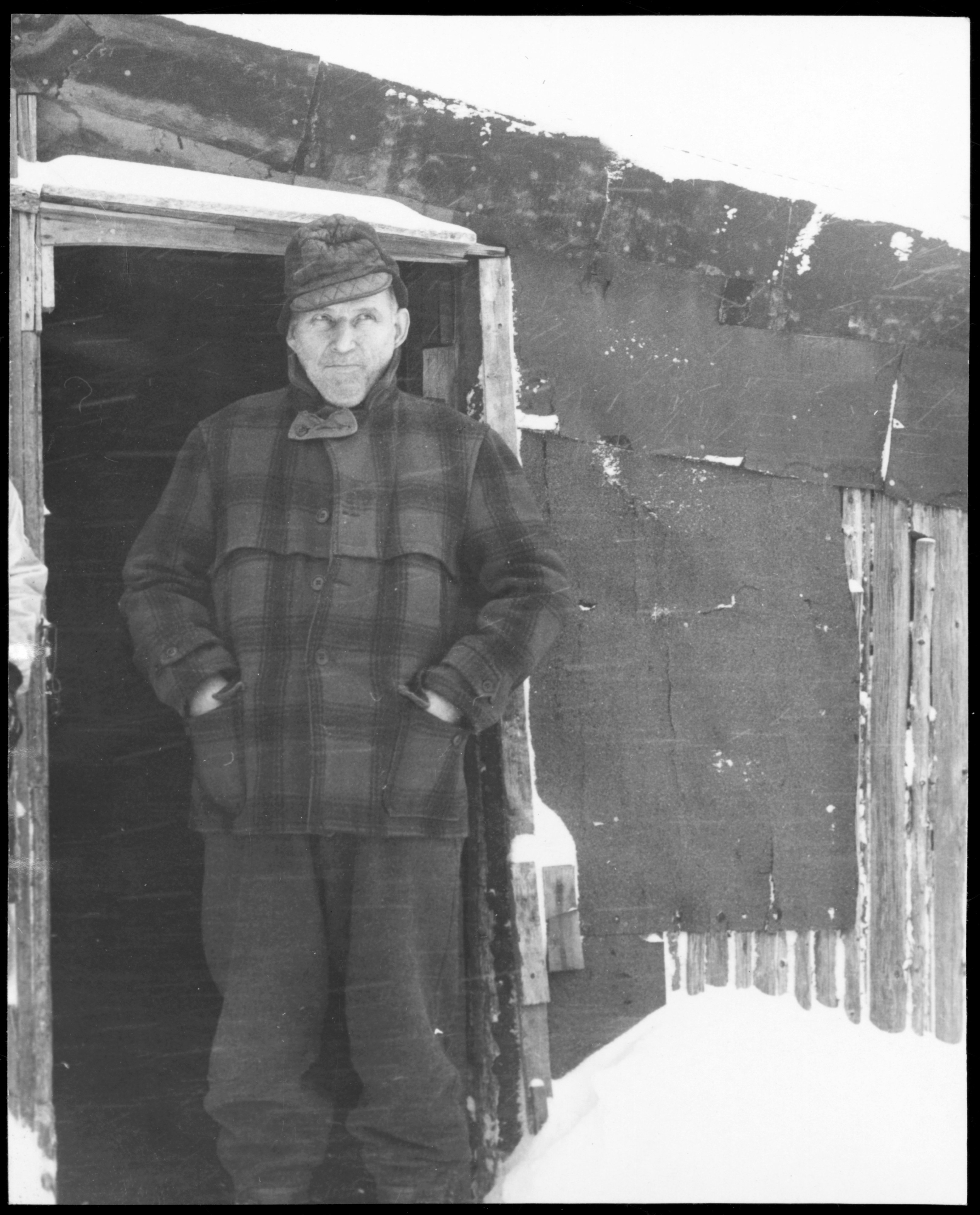

Maggie Harrington preceded Bill Mattila in a life of solitude in Keweenaw County, but his story overshadowed hers ever after. Unlike Maggie, Bill was willing to talk to outsiders about his retirement to Brockway Mountain–especially if they brought a package of beer to loosen his tongue. Those who came to visit often expected, wrote one journalist, “gnarled, knobby-handled walking sticks” and animal-skin robes. They thought they would greet Bill in a cave and marvel at the scraggly length of his beard. But Bill Mattila, like Maggie, was just a person who made his own untraditional choices, albeit in a spectacularly beautiful place.

William F. Mattila was born near Baltic, Michigan, to Finnish immigrants John and Hilda (Karppinen) Mattila on July 18. The year of his birth ranges from 1914 to 1916, depending on the source consulted. In a stark contrast with the Harringtons, the Mattila family was a large one: the 1930 census said that young William had nine brothers and sisters, from oldest brother Oscar down to baby brother Sam. In subsequent interviews, the number of children grew to fourteen or more. Like so many other Finns south of Houghton, John Mattila had chosen to pursue work at the Copper Range Company and spent at least a decade in their employ. Hilda died of dysentery and kidney failure in 1930, when William was just a teenager, and not long after another son had been lost to the same illness.

It seems that life became more challenging from then on: John lost his job at Copper Range during the Great Depression and took a WPA job. As adolescent William grew into adult Bill, he became a lumberjack, working the woods around Adams Township for a lumber company. And, with war on the horizon, Bill joined many young men in registering for the draft. At twenty-five, according to his draft card, he stood 5 feet, 8 inches tall. Long days in the woods had tanned his skin. He had hazel eyes and brown hair; he was wiry but strong at 155 pounds. He had attended school through the eighth grade. Six months later, Bill Mattila was an enlisted man, joining up in March 1941. In June 1942, the military discharged him.

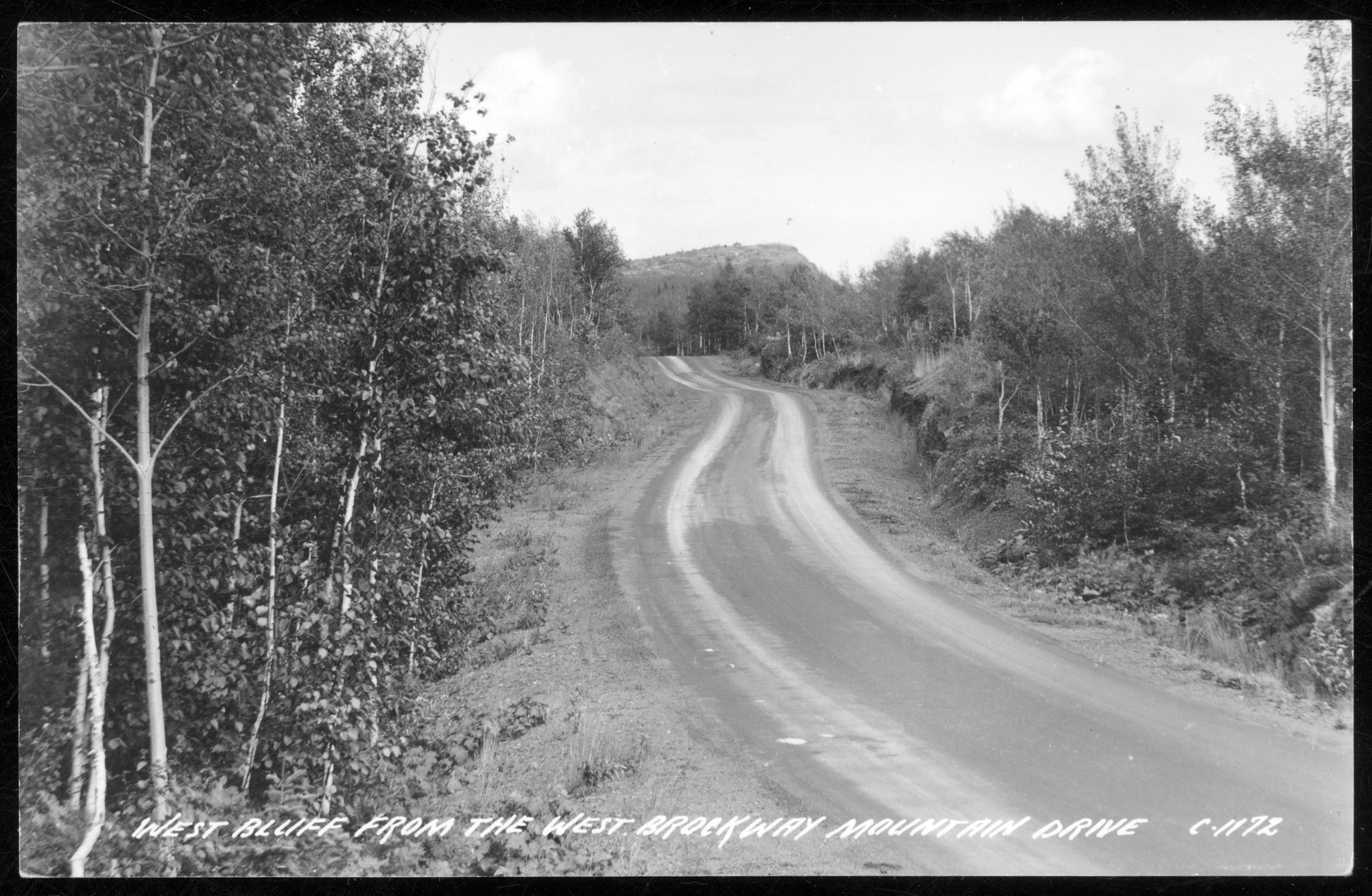

Bill later said that he worked in Detroit for a time before giving it up. He wanted “to live off the land as his grandfather had done in Finland years ago,” explained Mac Frimodig, who wrote a long tribute to Mattila in his book Keweenaw Character. His quest for simple, rugged living took him back across the Straits of Mackinac and nearly to the edge of the Keweenaw Peninsula, where he bought forty acres of land atop Brockway Mountain from the Department of Natural Resources. The simple cabin he constructed on a bare ridge of the property became his lifelong home–and a magnet for others.

The story of “the Hermit of Brockway Mountain” became one of the most widely circulated in the Copper Country. Tourists watched in fascination as Bill came down the mountain each month to pick up his mail and spend his modest military pension on cat food, batteries for his radio, and the few other necessities he couldn’t catch or grow. Curiosity-seekers who came to gawk sometimes found a terse reception unless they presented Bill with a pack of Stroh’s. For them, and for the occasional journalist, he launched into a colorful description of his life–featuring both honest depictions of an unconventional man and a little exaggeration that gave them some juicy copy to write. Bill’s devotion to his long line of dogs, whom he named Bark, and his cats, whom he dubbed Meow, remained constant, as did his passion for skiing the ridges and valleys of Brockway. His reliance on his radio for entertainment and his own two hands for crafting skis, furniture, and other tools also never changed. Almost without fail, he expressed deep satisfaction with the life he had chosen and the sound of the “four winds,” not human voices, that threaded through the walls of his cabin at night. He cherished the vista and the fresh air, the sky that opened above him and his rudimentary telescope at night. Brockway Mountain was not his place of seclusion; it was a retreat that unlocked the door to a world he loved.

Bill Mattila, like Maggie Harrington, died as he lived. He went down to Copper Harbor for a final resupply and returned to his cabin. The day that the townspeople anticipated seeing him again came and went, and those who went in search of him found that he had passed away in the home he built. With the date of his passing unknown, the official record designated it as January 1, 1985, about thirty-one years after Bill’s first summit of the mountain. His story remains deeply woven into the fabric of Keweenaw County, and the imprint he left on Brockway Mountain will always remain.

A heartwarming story of the best kind. A man and a woman who lived their lives as they pleased and died doing the things they loved. Never did they interfere with the lives of others. We are lucky to have this story to tell.