They crossed the ocean, and with them, they brought years of mining experience, spirited hymns, and pasties.

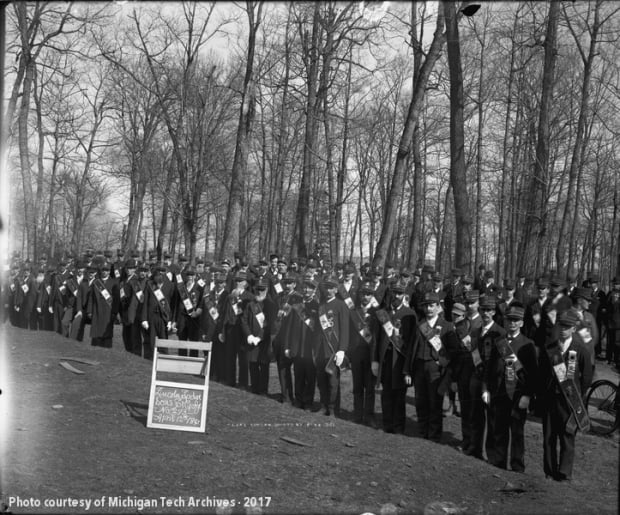

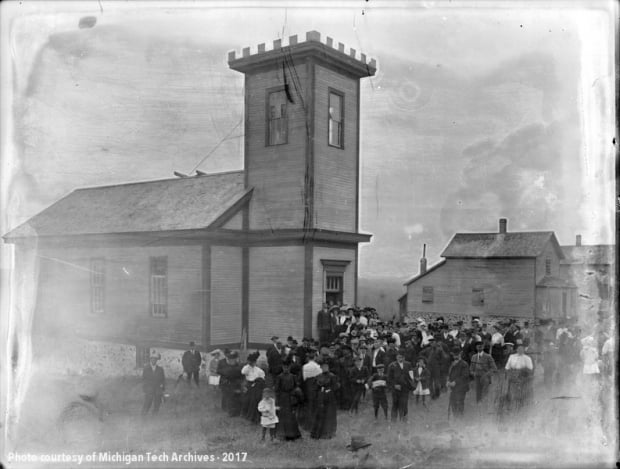

Countless Copper Country residents and descendants of former residents trace their heritage to one of the innumerable Cousin Jacks and Cousin Jennies–allegedly so named because the miners always spoke of myriad relatives by these names–who came to the region beginning in the mid-1800s. Copper and tin mining in the United Kingdom dated back to prehistoric times, and production soared to new heights following the Renaissance. By the time the 19th century dawned, generations of Cornish children had grown up in families whose subsistence depended on the mines. They watched their fathers take up lunch tins and walk down to jobs swinging hammers or holding drills underground, to occupations as carpenters or blacksmiths supporting mining operations. When they grew enough to be helpful, often at very young ages, boys and girls alike joined their family members in mining work. As men deftly removed rock from the ground, women skillfully processed it. No wonder, then, that when the newborn mines of Michigan sought capable workers, they looked to Cornwall. An exodus from that region began in earnest in the 1860s and continued for decades thereafter: every ten years from 1861 to 1901, according to the BBC, some 20 percent of men in Cornwall sailed away to seek opportunities elsewhere. Many of them chose the Copper Country as their next home, inviting other relatives to join them in the difficult but rewarding task of carving out life in a strange land. In its mines, in its communities, and in its kitchens, the new arrivals would leave a lasting impression.

Materials at the Michigan Tech Archives–including newspapers on microfilm, employment cards from major mines, naturalization records for certain counties, and other documents–can help to fill in the details of what happened to Cornish ancestors after they arrived in Michigan. What if you’re looking to go further back, however, and learn about your forebears’ lives before they crossed the Atlantic? A few resources can assist you in making significant strides forward in researching family members from Cornwall.

United Kingdom Census Records

Like the United States, the government of the United Kingdom compiled data about the sovereign’s subjects on a regular basis. Census taking in England began in 1801 and continued every ten years through 1931; the schedule for enumeration shifted somewhat in the face of World War II. For the first four censuses, data collected consisted primarily of the number of inhabitants in a given parish or place, their breakdown by gender, the number of dwellings, the types of industries or occupations the residents were engaged in, and other general demographic information.

Fortunately for genealogists, in 1841, the decennial census expanded to incorporate more personal details, such as the name of each resident, his age (rounded down to the nearest multiple of five if he were older than 15), the occupations of those working, and whether each inhabitant was residing in his native county. The 1851 census added more details, like marital status, specific places of birth, and relationships among household members. Subsequent censuses varied in the questions posed and may have expanded information about the size of a dwelling, length of a marriage, self-employment, etc.

Many future Cornish immigrants to the Copper Country will have been captured in at least one of the census records, and these documents can be tremendous assets in establishing family relationships and potential home parishes for further investigation. Likewise, in observing when an individual appears to vanish from British censuses, the astute researcher can sometimes narrow down when that person emigrated.

The valuable UK census, however, is also the expensive UK census. Access to its contents without charge requires a visit to either the National Archives in Britain or a LDS Family History Center, neither of which is particularly feasible under current conditions. Subscription services, including Ancestry and FindMyPast, can offer remote access for a membership fee. If you anticipate spending a great deal of time researching in England, FindMyPast also provides a number of digitized British newspapers available for keyword searches.

UK General Records Office (GRO)

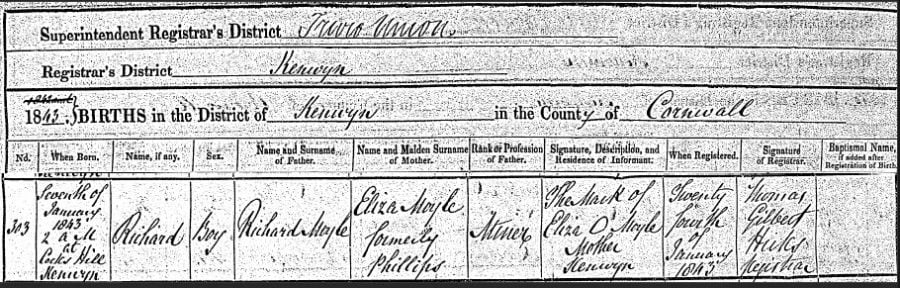

The census constitutes just one portion of the government-produced records available for Cornish genealogy. In 1837, England established a system to register births, marriages, divorces, and deaths civilly–that is, not strictly within ecclesial records. Civil registration gained traction somewhat slowly, especially in the case of births; some parents failed to appear before the appropriate governmental authority to report a child’s birth, instead preferring the traditional practice of presenting the newborn for baptism. Laws imposing a fee for late registration of births took effect in 1874, boosting compliance. If your ancestors were born before 1874, it is still extremely worthwhile to check the civil records!

As with modern American birth records, the typical civil registration of an English birth gave the child’s name, gender, date and place of birth, and parents’ names, including the mother’s maiden name. It noted which parent had provided the information to the registrar, as well as the date of registration and which official took down the data. Death records likewise captured the essential information about the deceased–name, age, gender, occupation–along with his place of death, cause of death, and particulars of the person making the registration with the government.

By creating an account with the UK General Records Office (GRO), genealogists can peruse indices of birth and death registrations; these, along with similar resources for marriage records, can also be found at FreeBMD, an open transcription project. The information available through the indices includes only the essentials–the mother’s maiden surname only, for example, rather than the full names of both parents–but researchers interested can place orders through the GRO for scans of the original documents in exchange for a modest service fee.

Cornwall OPC Database

For those specifically researching in Cornwall, the Cornwall OPC Database represents arguably the most powerful resource available–and it is entirely free.

Before the introduction of the civil registration system, the Church of England constituted the primary means of capturing the major events of life, including births (via baptism records), marriages, and deaths (via burial records). The state church continued to be an important producer of these records after 1837, as well; it was joined by an increasing number of Methodist and other “non-conformist” Christian faiths as revivals pulled Cornish laborers away from the established denomination. Through the dedicated efforts of parish volunteers, the Cornwall OPC Database presents transcribed, searchable versions of ecclesial records stretching from the 1500s into the early 20th century. Beyond vital records, the website also incorporates some special indices, such as the names of certain institution inmates, agreements between supervisors and apprentices, and a selection of paternity suits.

Although chronological coverage fluctuates by parish, the database truly unlocks decades, if not centuries, of family histories throughout the county of Cornwall. In general, it is reasonable to expect some sort of parish records from the 1800s (when most Cornish emigrants to the United States departed) to be available. Copper Country genealogists can then thoughtfully work backward from their known immigrant ancestors to their mysterious predecessors.

Keep in mind that, when searching this or other British databases, the spelling of both given names and surnames can vary dramatically over the years. Avail yourself of the “Include similar surnames” feature on the Cornwall OPC Database to check for records that may have been filed under a variation of the family name. Also remember the important of broadening your search: if you’re looking for “Rosemergy,” try searching with just “Rosem” to capture potential misspellings; if you seek “Johanna,” try just “Jo” in the event that someone spelled her name as “Joanna” instead.

And there you have it: a few resources, both free and paid, that can help make your genealogical journey across the pond easier. Do you have any tips or websites of your own to recommend? Please feel free to leave a comment here or on our social media! If the Michigan Tech Archives can at all be of service, please do not hesitate to e-mail us at copper@mtu.edu.

Holy WAH and Holy WAH again interesting