A job in the mines of the Copper Country could mean much to a man. It might have placed him working alongside his brother or his father; it might have been his first time employed as an adult. It might have offered him a toehold in a nation he hoped to claim as his own; it might have been merely a way to earn money and return to life in the old country as quickly as possible. Yet while working in the mines offered economic opportunity, it also carried a substantial cost. At the height of the industry, a man died every week while on the job, leaving a hole in the family that he was trying to support and better.

Genealogists often come to the Michigan Tech Archives in hopes of learning more about relatives who met tragedy in our local industry. In some cases, these men perished; in other instances, they were gravely injured and carried the scars of the accident for the remainder of their lives. If you have an ancestor whom you believe to have died in the mines, how can you go about verifying your hypothesis and learning more about his death?

Let’s consider an example from my own research. Samuel Henry Broad was born in Cornwall in 1856. By 1880, he worked as a miner at Central; in 1881, he married a fellow immigrant, Elizabeth Ann Hosking. From the 1894 state census, I saw that they remained in Keweenaw County for at least another decade. The 1900 census recorded Elizabeth Broad as a widow in Hancock, residing with her five children and her own father. What had caused Samuel’s death?

Since I knew from the 1880 census and from his marriage record that Samuel had spent at least part of his life working as a miner–and because it was obvious that he died young–I considered the possibility that he had died at work. To investigate this, I started to connect the dots with documents.

Looking for a death record. From the records I already had, I knew that Samuel’s death must have occurred sometime between 1894 and June 1900, when the census for that year was conducted. Although Michigan required deaths to be reported from 1867 on, consistency in documentation did not emerge until the introduction of death certificates in 1897. That meant that finding Samuel’s official death record could prove difficult, if not impossible, to locate.

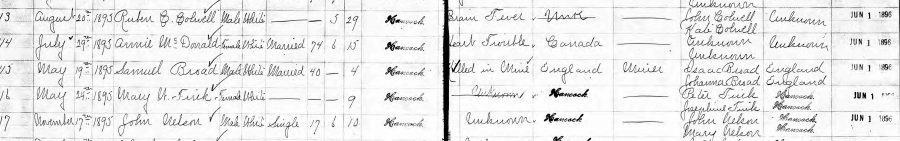

In this case, I was fortunate. I found a scanned ledger of Houghton County deaths on Ancestry that stated that Samuel had lost his life on May 19, 1895; his cause of death was “killed in mine.” My suspicions were correct.

If you’re looking for someone who passed away after the introduction of death certificates in 1897 through 1952, you can also search for them for free on Michiganology, an online portal to the Archives of Michigan.

If you can’t locate a death record. What if I hadn’t been able to retrieve Samuel’s death record? Other resources could help to fill in the gap. FamilySearch has a large number of probate files from Copper Country counties, especially Ontonagon and Keweenaw, that can provide an individual’s date of death. Although more common for individuals who had property to bequeath, these documents can help to supplement gaps in death records. In the absence of a probate file, try checking cemeteries or narrowing the possible years of death through other records. A man who appeared in the 1900 census and whose wife remarried in 1904 may well have died in the intervening years.

Finding the details of the accident. Some researchers may be satisfied just to know that their ancestor died in a mine accident. If that’s you, once you’ve verified the death through some means, you are all set! In my case, I wanted to go deeper. What had happened in the mine to kill Samuel? In which mine had he met his demise?

How you go about ascertaining the details of an accident will depend on the particular circumstances of your ancestor’s life.

If you know where your ancestor lived or what company he worked for already, try to find an employment record. Calumet & Hecla faithfully documented the deaths of its workers, and the employment card of an individual killed there will usually include a brief summary of the accident. C&H maintained an interest, as well, in laborers who had left its employ and occasionally would note on the appropriate men’s records if their deaths had occurred at rival companies. If you suspect that your ancestor worked at C&H at any point in his career, his record would be well worth locating, if possible. The Michigan Tech Archives can help with that.

Keep in mind, however, that collections of employment records are not always complete. In Samuel’s case, I saw that he died in Hancock, which made me suspect that he worked at the Quincy Mine. Unfortunately, employment cards from Quincy are largely nonexistent before 1900, and I didn’t have any luck finding Samuel among them. Records from other mines near Hancock–such as the Pewabic or Franklin–also have not come down to us.

If you have the date of death (exact or approximate), check the newspapers for an obituary or a news report of the accident. With a few gaps, newspapers held by the Michigan Tech Archives cover the period from 1868 to the present. A man’s death in the mines may have been documented in the local news, especially if his demise transpired in a particularly violent way. Although newspapers often presented the news with a bias toward the company, the details of where an accident occurred and what occurred are often accurate.

While the archives are currently closed to the public, newspaper articles can be retrieved by staff upon our return to the office. Through the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America project, some local titles can be browsed from home, including the Copper Country Evening News from 1896 to 1898 and the Calumet News from 1907 to 1914.

To my surprise, I found the report of Samuel’s death in the Quincy Mine in a place other than what I expected. The Copper Country Evening News picked up the story of his demise in its March 21, 1896 issue, explaining that the unfortunate man had died just two days earlier.

Justice Finn impaneled a jury yesterday morning and held an inquest into the death of Samuel H. Broad, killed in the Quincy Thursday afternoon. The jury was composed of Joseph Malberbe, Henry O’Leary, D. Lanctot, John Doyle, James Sullivan, and Joseph Wareham. William Gross, a partner of the deceased, told the story of the accident. They were working in a stope at the 38th level, north of No.6 shaft. A blast had been fired, and the two started to climb up about 10 feet to the face of the stope, one on each side. A piece of hanging fell, burying Broad and some of the flying pieces struck Gross. The latter got the fallen rock off his companion as quickly as possible, but the unfortunate man died a few moments after. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with these facts. Mr. Broad’s family consists of five young children, and they are left in not too comfortable circumstances.

This added detail and color to my understanding of Samuel’s passing, and it corrected the death record I had found previously.

If you know that your ancestor died in Houghton County, but you aren’t sure when. The Mine Inspector for the county prepared annual reports summarizing men who were killed or seriously injured on the job that year. Although these documents may have also been produced by other counties, the Michigan Tech Archives has not received any such publications for places outside of Houghton County. For those seeking information about accidents at the heart of the Copper Country, these bound volumes are easy to skim for information–though the information itself may be brutally difficult to digest.

May we help you to search for ancestors affected by mining accidents? Although staff have not yet returned to the Michigan Tech Archives, we would be happy to consult with you on your search options and to add your request to our queue. Feel free to e-mail copper@mtu.edu to move forward in your search.

Very good research. Do you know what happened to Samuel Broad’s descendants? How did his widow and five children survive without Workers Compensation and Social Security survivor and orphan benefits?

Thank you for your kind comment and your question! Given their straitened circumstances and perhaps the memories of Samuel Henry’s death, most of the Broads chose to leave the Copper Country in search of a new life elsewhere. By 1907, at least one of the children (Clara, born in 1882) was living in Butte, MT, where she married near the end of that year. When the 1910 census was taken, Samuel Henry’s widow Elizabeth and several of the Broad children resided in Spokane, WA. Sons Samuel John (born in 1884) and Alfred (born in 1892) had found work as house carpenters. Charles Henry (born in 1888) had joined the army and was stationed near Seattle. Only Richard (born in 1890) remained in Michigan, where the census recorded him as a railroad worker. He apparently saved enough money to put himself through an engineering program at the University of Michigan; he later relocated to Virginia as part of his new career.

The Broads who had headed west eventually settled in California to live out the remainder of their lives. They appear to have pulled out of poverty and achieved a modest middle class existence.

Samuel Broad is somehow related to my Rowe family. Henry Rowe’s third wife was Joanna who had a daughter named Emily. Isaac and Samuel are redlated to her but I dont know if it is brother or daughter. She died c 1906 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Eagle River next to Henry and this first wife and youngest son. The plot has a big rectangular stone with “Rowe” on it on the lake side and has an iron picket fence surrouinding it.

Yes, Samuel Henry Broad is Jane Broad Rowe’s baby brother! Several members of the Broad family settled in Central, including Jane (who, as you mentioned, later married Henry Rowe), Johanna (married to John Glasson), and Eliza (married to Richard Peters). They certainly did their part to contribute to the Cornish atmosphere of the town!

I wrote some chapters on deaths in the mines for the book, Cradle to Grave. These chapters provide a good overview of the incidence of fatal accidents, and the social reaction to fatal accidents. Jack Martin, a sociologist, and I put together death data on every victim we could identify, (about 1,900) which included name, age, ethnicity, company, type of accident, sources of information on the victim’s accident, among other things. I added all this data onto worksheets that you can now find in the Larry Lankton collection at the Tech Archives. The data are entered by year. It is a very handy source.

A very handy source indeed and one often overlooked! Thank you for your comment.

I know when. Gottlieb Wappler (the record reads as: Godlope Wapple) died January 29, 1867 at the Petherick Mine (however I have also seen the year as 1868 – depending on how you read the record). He was my great-great grandfather and he and his spouse and 6 children all lived in Copper Falls (now extinct/disappeared). I still don’t know where he was buried. His grandson, Franklin Warbler, had a rock fall on him at the C & H on April 19, 1912 – went into a coma and died April 30, 1912 and is buried in Lakeview Cemetery in Calumet. I think the payout on his death was $500 and his parents, siblings, their spouses and children all moved en masse to Detroit by the end of the summer of 1912.

Finding the burial locations for those early mining casualties and others who passed away in the first few decades of migration to the Copper Country can be quite a challenge! It’s always frustrating to our staff when we are trying to help patrons and run into dead ends (no pun intended) in the resources.

I found this very interesting. My grandfather is John Vivian who was Superintendent of the copper smelter and lived at the top of East Street. He had five children Elizabeth (who taught in Marquette), John (who moved to Ames IA), James (who resided in the Houghton area practically all his life and still has children living in the area), my mother Alice who went to Michigan State and spent most of her life working at MSU) and their sister Jean (who spent most of her life in Marysville OH)

Enough said.

It’s always fun to hear about other families connected with the Copper Country! Thank you for reading the blog and for sharing.