To Copper Country locals, “White City” today evokes images of a sandy beach–a rarity in the Keweenaw–with the Huron Mountains’ verdant, distant slopes rising above a glistening Lake Superior. Visitors reach this beach by driving south from Lake Linden toward Jacobsville, following a winding township road that offers glimpses of Torch Lake. A hundred years ago, however, a trip to White City took a different path–and led to an experience that would surprise today’s sunbathers.

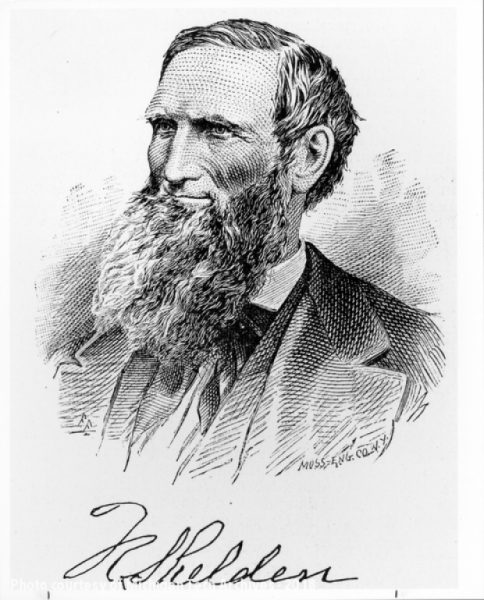

From the first days that settlers began to arrive in the Keweenaw, the advantages of White City’s location were universally acknowledged. In the mid-1800s, no one had yet attached a romantic name to the place. Rather, reflecting its position at the point where Lake Superior narrowed and Portage Lake began, residents called it “Portage Entry” or simply “the Entry.” Enterprising businessmen set up stores to provide waterborne travelers with necessities–at a price–as early as the 1840s. Those journeying into the Portage could acquire the last items needed to complete their trip, while boats just passing by could resupply without venturing into town. Ransom Shelden arrived in 1847 and promptly opened one such business, whose success eventually led him to found the town of Houghton.

In the later years of the 19th century, the Entry began to change. Discovery of sandstone nearby led in 1883 to the establishment of quarries and a town, Jacobsville, to house their workers. The profitable, sizable operation drew attention anew to the Entry and to its recreational possibilities. Meanwhile, hundreds of miles south, the World’s Columbian Exposition sprang up from a Chicago swamp to become a wonderland of electric lights and ivory paint. The people who wandered awestruck through the fairgrounds christened them the White City, a name that quickly became part of the American lexicon.

In 1906-1907, promoters began to seriously investigate the Entry as a place to establish an amusement park and resort. The new venture would not be the first of its kind in the region; Electric Park had set the precedent in 1902. But this place would offer benefits that Electric Park could not: Lake Superior and particularly ample ground for construction. Around this time, the Entry adopted its new, more cosmopolitan name: White City.

Under the management of George Hocking, plans for White City took on a larger scale. To this point, recreational facilities there had been limited: a dance pavilion and a modest dock constituted everything not provided by nature. As local historian Clarence Monette explained in his 1975 book White City: The History of an Early Copper Country Recreational Area, Hocking’s crews began in 1908 by erecting a porch, ideal for strolling or sitting, around the original pavilion, and extended the original dock. Taking advantage of his proximity to the Jacobsville quarries, Hocking ordered that a sandstone sidewalk be laid from the dock up to the pavilion. A hotel arose nearby. Visitors arriving at White City in the early days could not fail to notice that its manager had painted all structures a brilliant white, in keeping with the name.

And arriving, in those days, meant a particularly picturesque voyage. Pleasure seekers journeying to the Entry had long relied upon steamboats that chuffed down through the Portage and deposited them at their destination for about fifty cents per round trip. As White City grew, so did the demand for this transportation. Steamships bearing names like Plow Boy, Uarda, R.B. Hayes, and International glided over the waters, brimming with excited passengers in hats, suits, and lawn dresses. Orchestras provided dance music that whet their appetites for White City’s band or allowed them to continue the party all the way home. Monette noted that moonlight excursions aboard these vessels achieved special popularity.

White City’s successful first summer, buoyed by the fine location and charming transportation, segued into another. With revenues on the way up, the management turned to a Houghton architect, Paul MacNeil, to expand and improve White City’s facilities. A restaurant lodged in the pavilion gained a dedicated dining room in the remodeled hotel, where it could continue to serve its specialty: Mrs. Hocking’s “planked whitefish dinners with ice cream and cake for dessert.” In 1909, the newly-incorporated White City Company handed primary responsibility for the property from George Hocking to W.H. Labb. Labb, whom Monette described as “a great promoter,” encouraged journalists and gawkers to visit White City and look over his developing scheme for the property. He began an aggressive brush-clearing campaign and planned to demolish a series of fishing cabins on the shoreline, which would be replaced with rental cottages. Bathhouses blossomed along the 1,500 feet of White City shoreline, and a new, even larger dock emerged for steamships. A saloon adjacent to the restaurant and hotel provided more exotic drinks to adult guests. Those looking to indulge another vice could step to the rear of the saloon for casino games and rooster fights conducted by an out-of-town operator.

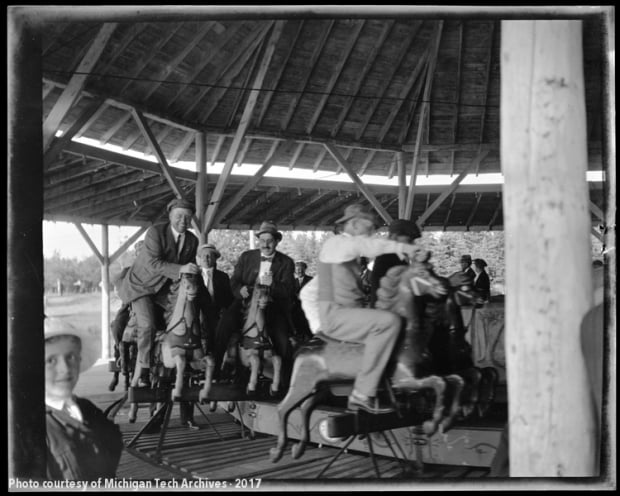

Positioning Coney Island as his ideal, Labb schemed up a vision for White City that surpassed anything ever seen at the Entry. He put in a wooden merry-go-round, complete with a stable of carved horses, beneath a canopy. Adults and children alike delighted in riding their ponies around the carousel, powered first by a steam engine and then a gas one. In an even more ambitious effort to bring Coney Island to the Copper Country, White City’s promoter built a roller coaster–the only one ever installed in the Keweenaw. According to Monette, the track began “from a large building that consisted of a wooden floor and large poles that held up the domed roof,” similar to the carousel building. After boarding, passengers had a rollicking ride over a half-mile figure eight track, the predominant style of roller coaster in the early 20th century, before being deposited back at the station. An oversize electrical plant supplied power for this thrill ride, as well as hundreds of lights throughout White City. Unfortunately, Monette noted, “this item of amusement must have caused a few problems, as it did not remain in the park very long.” The roller coaster’s launching station was repurposed as a lounge, and archival images of its former use are difficult to come by.

White City continued to flourish in popularity and profitability into the mid-1910s. Despite a few setbacks–the loss of certain steamers, the removal of the roller coaster–the management succeeded in expunging their debts, catering to large groups, providing a variety of tasty meals, and offering an outing with varied appeal, including the additions of new amenities. Rental cottages booked quickly and remained full through each summer season. The park stayed busy through the strike and into the first years of World War I. Then, as now, who could resist a fun trip to a beautiful spot on the Lake Superior shoreline?

The difficulties began in earnest, Monette said, with Prohibition. Michigan jumped on the train earlier than most states through a state constitutional amendment that voters approved in November 1916, several years before nationwide adoption. This kibosh on selling or manufacturing alcohol meant that the money-making White City saloon was officially shuttered. In 1917, the United States entered World War I, and doughboys began sailing overseas. Patriotic fever gripped the country. Woodrow Wilson’s administration called on Americans to purchase Liberty Bonds and to have “meatless and wheatless” days. The cumulative effect, Monette said, was for “numerous people [to believe] that it was not patriotic to take vacations, outings, or have other enjoyments when hundreds of young men had left town and gone into the service.” Money and time went to war efforts rather than leisure, and social groups that would normally patronize White City en masse began to cancel their trips. Its operators reduced their offerings to the dance pavilion and campground, trying to reduce expenses. Under these circumstances, a difficult summer season or even two might have been survivable. When 1919 also proved sluggish, however, White City’s managers turned out the lights for the last time.

In September of that year, White City sold its last steamboat, the A. Wehrle, which departed for Duluth. Workmen dismantled the merry-go-round, then the dance pavilion. The summer cottages and the powerhouse that had energized White City’s roller coaster remained for many years, supporting groups that would come to camp. Today, little remains but the name, joining its compatriot at Electric Park.

I can just picture the pretty ladies and dapper gentlemen strolling arm and arm enjoying the matchless

U P summer! I Wow what a picture this writer has painted………….Thank You