Planes, trains, and automobiles: there was a time when a person bound for the Copper Country could choose any of the three ways to travel. Although many decades have passed since train whistles echoed through Keweenaw towns, cars naturally remain popular, and our Houghton County Memorial Airport continues to serve Copper Country fliers.

Early airports on the Keweenaw Peninsula could be found at a few different locations. Seaplanes, of course, were ideally suited to communities surrounded by water, and many pilots landed their amphibian crafts on the Portage Canal or local lakes. By 1931, the United States Bureau of Air Commerce’s Airway Bulletin advertised two primary airports available in Houghton County. On the Isle Royale sands, a feature near Houghton created by stamp sands dumped from the Isle Royale Copper Company’s mill, pilots could find a field of “irregular shape” and a runway 3,600 feet long. Two years later, an airport opened on the east side of Laurium, providing three landing strips maxing out at 2,000 feet. The grand opening was a cause for much celebration, with Calumet & Hecla’s company band providing music for the occasion and “a thrilling air show by local and visiting pilots” delighting onlookers. At the time, according to the Daily Mining Gazette, “pilots who used the new airport… declared it to be one of the best situated in the Upper Peninsula and said that, when completed, the field will rank among the best in the state.”

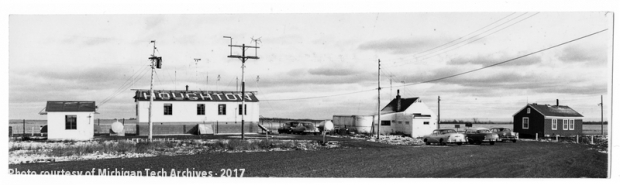

The aviation needs of the Copper Country, however, soon exceeded what these airports could provide. In the mid-1940s, discussions concerning a new airport began in earnest. Proposals were advanced to build near Dodgeville, as well as near Oneco, an area between Calumet and Hancock. Like many large projects, the new airport encountered its share of delays. Once Oneco was settled upon, boosters sold subscriptions to defray the cost of purchasing the 578-acre site. Their drive was highly successful, exceeding fundraising goals, but various disagreements about who would be responsible for the airport and “legal entanglements” postponed the purchase. Finally, according to an October 1946 note in C&H’s company newsletter, the sale went through and work began. Industrious Yoopers living adjacent to the new airport descended, clearing the land in exchange for the firewood they produced from it. Plans for that fall also called for grading an air strip about a mile long, installing a broadcasting station and antenna north of the airport, and constructing a guard house and control station at the site itself. Other additions throughout 1946 and 1947 included installing field lights and a beacon; contractors also crushed and stockpiled rock for eventual paving of the runways.

In September 1948, Houghton County Memorial Airport, named in honor of American pilots killed in battle, finally received its dedication. C&H’s newsletter noted that almost 20,000 people and more than 100 aircraft were on hand for the festivities, which included military ceremonies, a speech by the governor and a representative of the Canadian Air Service (which had collaborated on the project), and an air show deemed “the greatest… ever staged in the Upper Peninsula.” Naval aviators provided examples of how they would land on aircraft carriers, “other groups flew in various formations over the field,” and spectators delighted at the sight of two jet aircraft, perhaps the first in the Keweenaw, performing a flyby.

Over the next two decades, the airport received various improvements, such as a paved runway, a Vortac radio-to-air navigation system, and renovations of its hangars. It also became a site of research on some of the Copper Country’s most relevant topics: snow, ice, and frost. Military and civilian investigators alike tested new snow conveyances and removal equipment at the airport as part of the Snow Ice Permafrost Research Establishment (SIPRE); a version of this group continues to operate near the airport as Michigan Tech’s Keweenaw Research Center, the university’s official snow tracker.

Changing circumstances in the community, however, once again prompted changes at the airport. In the late 1960s, the Copper Country lost its passenger rail service, shifting long-distance travelers to cars and airplanes. Meanwhile, local merchandisers and manufacturers, like Pettibone of Baraga, had come to rely on air shipments of small goods. As they had in the 1940s, boosters again rallied and distributed promotional materials championing a dramatic renovation of the Houghton County Memorial Airport. “Our airport served over 50,000 passengers and 13,000 aircraft in 1968, second only to Marquette in the Upper Peninsula,” one such brochure stated. “Growth in service has exceeded all expectations, yet we have essentially the same runways as when the airport was built 21 years ago.” They cited deep potholes that opened on the strip every spring and a freeze-thaw cycle that defied patching attempts. Additionally, “the main runway often is unusable, and crosswinds on the other runway cause many flights to be cancelled. Until we have a permanent, dependable runway, we are harbor conditions for a tragedy.” The brochure also called for upgrades to the two hangars (“literally… falling apart”), the terminal building (where “waiting passengers are often jammed together shoulder to shoulder”), and the crew house (“a tarpaper shack”).

“A community without a modern airport will be bypassed by industry, just as communities were bypassed 100 years ago if they were not near a railroad… surveys show that 57% of [manufacturers] will not locate where there is no modern airport. Business growth and aviation are linked hand-in-hand.”

But it was not only industry that would benefit from a new airport. “Air service is vital for medical emergencies when sick people need quick care outside the area or special medicines flown in.” Senior citizens increasingly preferred flying to long trips by bus or car, said the brochure, and tourists and those visiting family savored the convenient speed of air travel. First class mail also came to the Copper Country exclusively by plane. In short, concluded the brochure in capital letters, “THE AIRPORT IS FOR EVERYBODY!”

To improve and lengthen runways and taxiways–which required further land purchases–and expand terminal facilities, an investment of $3.8 million was estimated. State and federal agencies agreed by 1969 to put up some $3.2 million of the price tag, leaving $600,000 to be raised locally. The Houghton County board proposed to residents a five-year millage to collect the funds, bringing it up for a vote on May 5, 1969. Perhaps won over by the persuasion of circulating brochures, the voters said yes. Earlier that day, C&H’s new parent company had announced that the mine would never reopen. The old Copper Country economy went out on the same day that the new airport came in.

Dignitaries marked the ceremonial start of construction in November 1971. By this time, the proposed airport had also grown to include an airpark, a commercial center that would house several businesses. Companies at work on the development included Yalmer Mattila Contracting, Ken Roberts Construction Company, and Michigan Bell Telephone. Just under a year later, on October 28, 1972, a grand opening and ribbon cutting was held at the new facility. At 9:30am, a North Central Airlines DC-9 landed, a red letter event. While jets had flown by at the 1948 opening, Houghton County runways had never been capable of landing jet aircraft. The arrival of the 99-seat North Central DC-9 marked the first time one of these planes ever alighted in Houghton County. It would repeat the feat throughout the day, offering rides to excited visitors. A ceremony in the new passenger terminal featured speeches by state and national government officials, a review of project highlights from the construction supervisor, a cornerstone dedication, and, naturally, a ribbon cutting event. After high school students served an informal lunch in the new hangar, the thousands of visitors were free to mill about the new facilities or queue for jet rides.

The expanded airport ushered in a new era of service that has continued to this day. Of course, the trip has not been without some turbulence. By 1982, the northwest-southeast runway showed severe degradation along its 6,500 feet–ten years before it was expected to fail. The airport also encountered budget struggles that threatened its shutdown, and public squabbles marked its leadership at times throughout that decade. Flights, for the most part, have been without incident, though on one notable, very Yooper occasion in 2000, an outbound plane hit two deer on takeoff. No passengers were hurt in spite of substantial damage to the aircraft.

North Central Airlines originally provided prop, then jet service to the airport and even ferried snowballs along its airways to Texas as a Winter Carnival tradition. Many nostalgically remembered the company’s logo, Herman the Duck, for years after the company had merged into a new Republic Airways. In the wake of the North Central merger, commercial flights from Houghton County have been provided by affiliates of various major airlines, usually under subsidies provided by the Essential Air Service (EAS) program. In 2009, Mesaba Airlines, a regional affiliate of Northwest-turned-Delta Air Lines, announced that it would terminate service. SkyWest Airlines picked up the contract that year and began to provide service on 50-seat regional jets, using the United Airlines banner and ferrying passengers to Chicago O’Hare. In early 2022, however, SkyWest filed notice of its intent to abandon the route. While EAS regulations prohibit discontinuation until a replacement carrier can be found, it seems that commercial flights to Houghton County are once again up in the air. Yet the airport will faithfully remain, allowing intrepid fliers to enjoy one of the most beautiful views aloft: the Keweenaw’s deep green ridges edged by the glistening blue expanse of Lake Superior.

A topical story for sure with the airline pulling out………..so sad they are going. The well written story was very interesting. Keitos