Paul Bergstrom and Tom Wallner generously shared their knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive Zoom webinar hosted by Dean Janet Callahan. Here’s the link to watch a recording of his session on YouTube. Get the full scoop, including a listing of all the (60+) sessions at mtu.edu/huskybites.

Doing anything for supper this Monday night at 6? Grab a bite with Dean Janet Callahan and Professor Paul Bergstrom for “Nanoscale Epic Fails!” Joining in will be one of Bergstrom’s former students, Tom Wallner, now an R&D engineer at PsiQuantum.

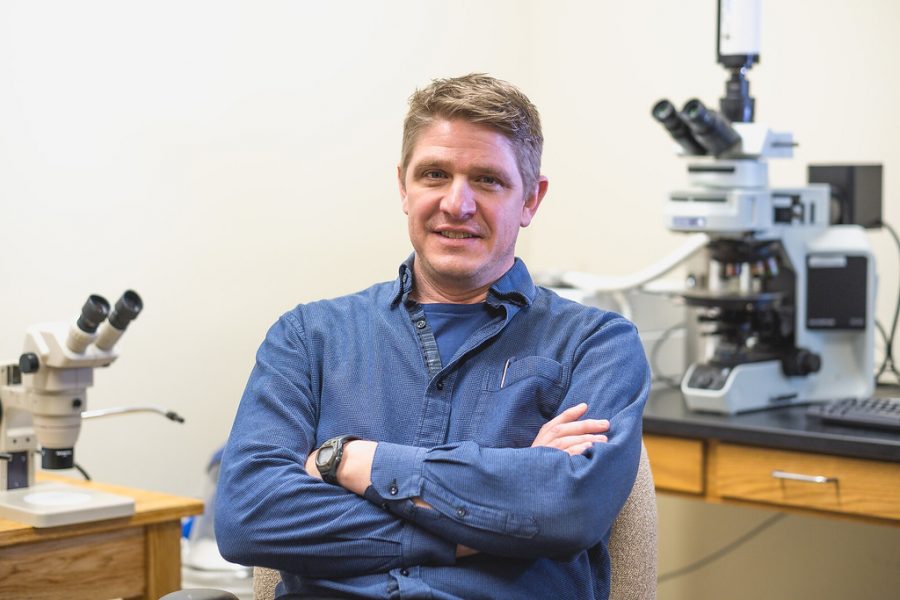

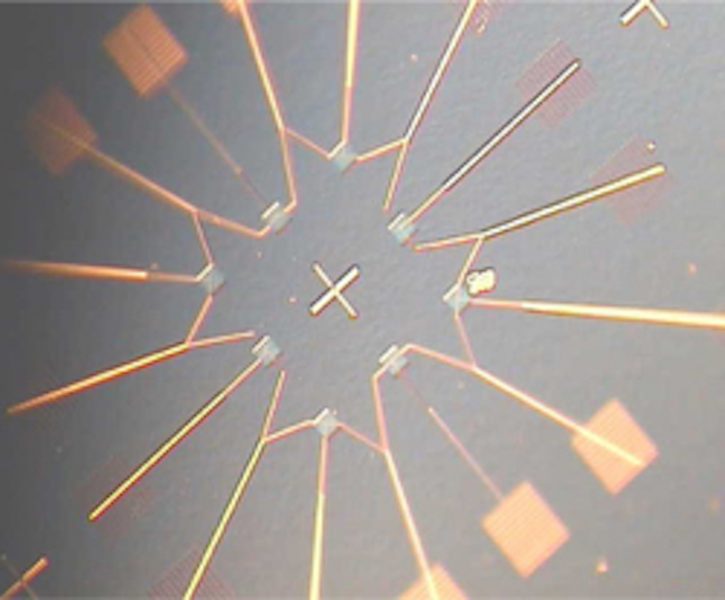

At Michigan Tech, ECE Prof. Bergstrom and his team of student researchers develop nanoelectronic devices. The effort takes them down some (seemingly) impossible pathways.

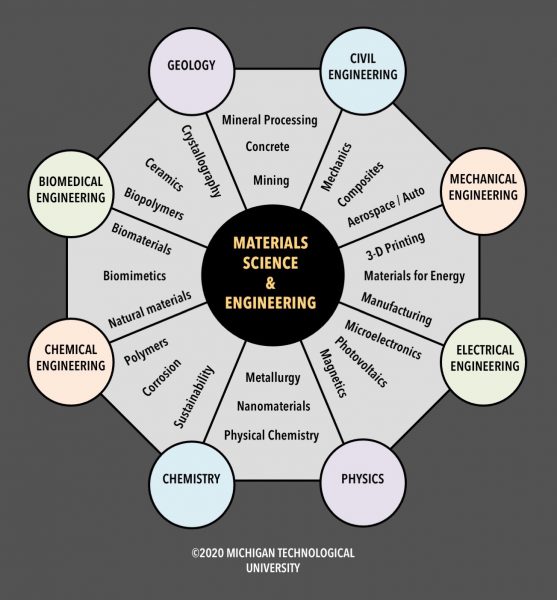

“Nanoscaled materials and devices that leverage quantum—or nearly quantum—scales enable extraordinary behavioral changes that can be very useful in sensing and electronics,” he says.

“Conducting research in this area constantly demonstrates that what we think we know is not always everything we need to know about how atoms and molecules interact. One experimental failure leads to understanding for the next. It’s a life lesson under the microscope.

“With the scientific method, we have an idea. We know where we want to go. We create a path to get there. Depending on our results, we decide whether or not we’re on the right path,” he explains.

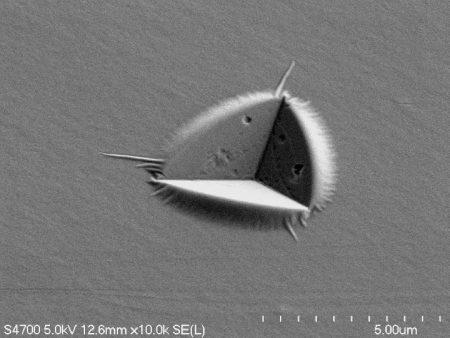

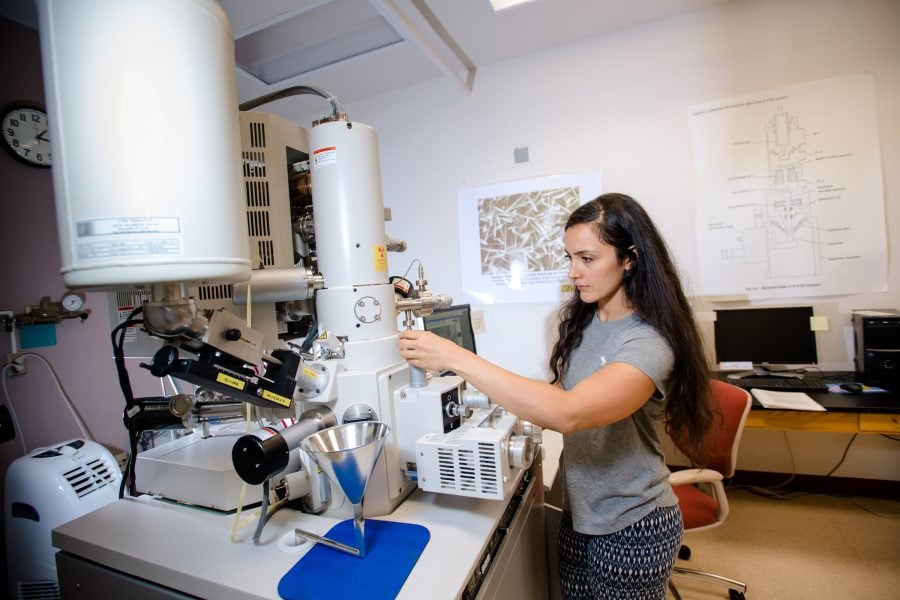

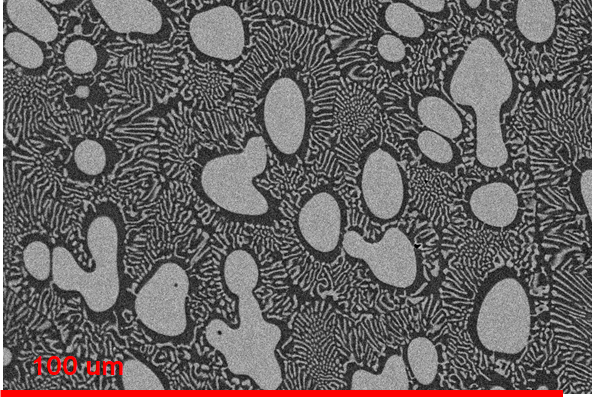

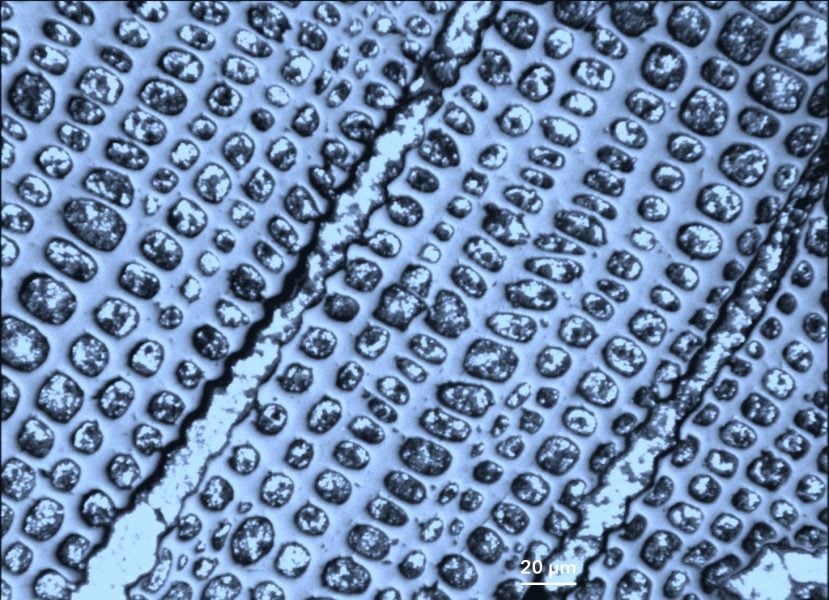

Working in the nanoscale, it’s all about the size of things, he says. Bergstrom and his team use focused ion beam (FIB) systems to fabricate electrical devices at the nanoscale, using elemental gallium. He’ll explain the process in detail during his session on Husky Bites.

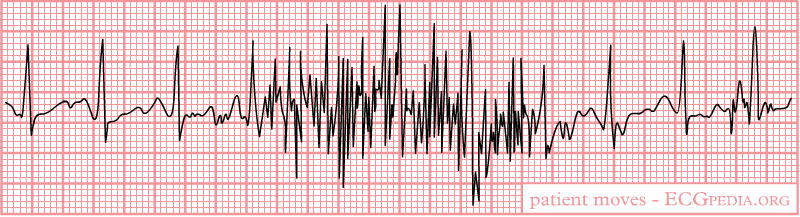

“We can see down to the 10s of hundreds of atoms and molecules, and see quantum mechanical effects that take place,” he says. “Many nanodevices exhibit quantum mechanical electronic behavior at subzero temperatures. There are lots of blind alleys we need to map out in order to understand where to go next with our research.”

“Experimental failure is not final. There can be success through failure, even epic failure.”

Bergstrom and his team had a goal: make a single electron transistor (SET) operable at room temperature. And they did: Theirs was the first operating SET of any kind accomplished with focused ion beam technology, the second demonstration of room temperature SET behavior in the US, and sixth in the world.

Room-temperature SETs could someday open up whole new aspects of the electronics industry, says Bergstrom. “Moving to nanoscaled electronic devices such as SETs that rely on quantum behavior will allow us to eliminate leakage current. The SET may also allow technology its continued migration toward high levels of integration—from hundreds of millions of transistors to hundreds of billions of transistors ultimately—so that cost per device will continue to drop at its historic rate, or even faster.”

Bergstrom’s effort goes beyond the SET. “We hope to find ways to create devices ultimately that will not transfer current when they do logic. That is the ‘Holy Grail’ for nanoelectronics. And we are taking that challenge seriously.”

He also takes it in stride. “In research, past failures define the starting place. Current failures define impossible pathways. We know our starting point and our end point. We just don’t know the path in between.” And that’s okay, even good, he says.

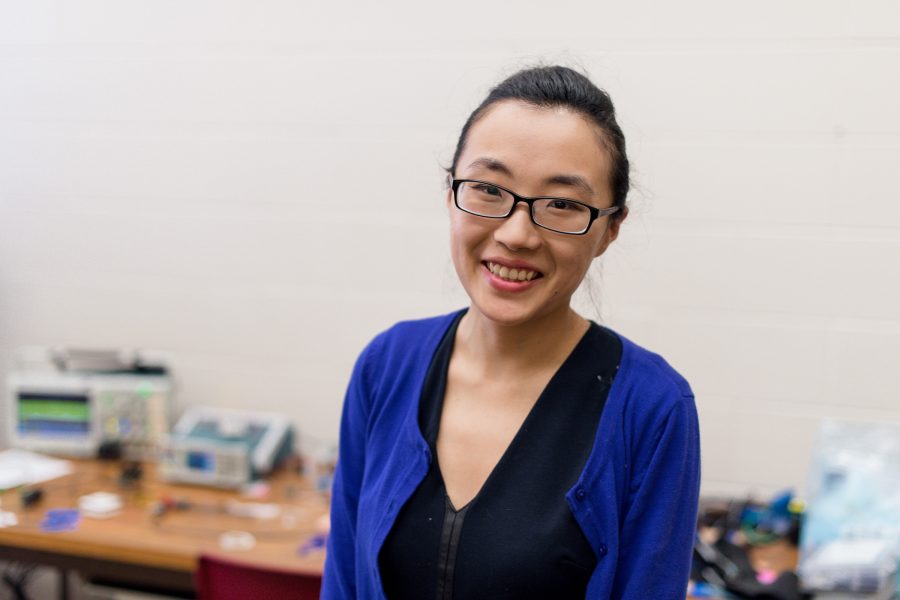

Michigan Tech alum Tom Wallner graduated from Michigan Tech with a BS in 2002 and an MS in ‘04, both in electrical engineering. “From my undergrad work and throughout my career I’ve built things,” he says. “I’ve always been especially interested in building small things.” That fascination has led Wallner to some amazing places and workplaces. He also found the love of his life at Michigan Tech, Jin Zheng-Wallner.

After graduation, Wallner spent time at Sandia National Labs, and then joined IBM doing microelectronics R&D, including time spent in South Korea for IBM, working with Samsung. After nearly a decade Wallner moved to GLOBALFOUNDRIES, “a company formed out of a bunch of fabs.” (AKA chip fabricators). Then one day Wallner’s career path took a fortuitous turn. “Some old IBM buddies knocked on my door, some very good friends. They said, ‘Hey Tom, do you want to try this photonics stuff?”

“It turns out testing photonics devices is a wide open field,” he says. “Not many people have a background and skill set in that area. I thought to myself, well, I know a little about photonics, I’ll just go figure it out.” Wallner went to work at SUNY Polytechnic Institute as an integrated photonic test engineer.

Recently Wallner joined PsiQuantum, a startup based in Silicon Valley. “Our mission is to build the world’s first useful quantum computer. We’re taking a photonic path to that, which is different than most quantum computing,” he says.

As a student at Michigan Tech, Wallner worked on a team that developed an unmanned vehicle. “It looked like a bumblebee—300 pounds of unmanned robotics, with cameras on it. We navigated it on a course we set up out on the Michigan Tech golf course.”

Wallner was a management advisor in Douglas Houghton Hall (DHH) and president of Michigan Tech’s IEEE chapter for 4 years. “I was in charge of the building. If a hallway light went out, or a door got jammed, OR the one time there was a water line break and a whole floor flooded–that was my responsibility,” he recalls.

“Tom not only renovated the IEEE student lab—he even secured industry sponsorship to cover the costs,” says Bergstrom. “The Kimberly Clarke plaque still hangs outside the door of Room 809 in the EERC.”

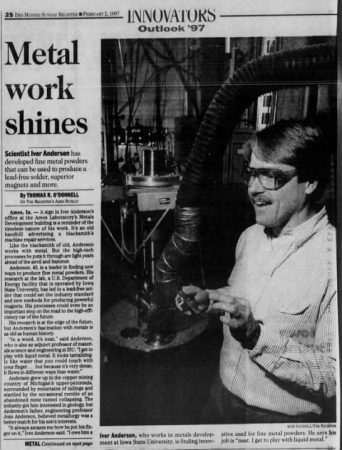

“Tom also started building the MFF for me, and he developed the tool set for our room temperature SET research,” notes Bergstrom. Today the Microfabrication Shared Facility (MFF) at Michigan Tech provides resources for micro- and nano-scaled research and development of solid state electronics, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), lab-on-a-chip, and microsystems materials and devices, serving researchers across campus and across the country.

Prof. Bergstrom, when did you first get into engineering?

I knew I wanted to be, specifically, an electrical engineer by the time I was 16. I am the son of an analytical chemist who trained chemical technicians for industry. When donated tools would come into his teaching laboratory, I would come in and either fix them or disassemble them and recycle the components that could be processed. A passion for high-end audio also led me to analog amplifier design and speaker assembly. My desire to learn about the coupled electromechanical physics and engineering in audio as a young teenager sparked my interest in electronics and microelectromechanical systems—and launched my career at the micro- and nanoscale.

Hometown, Hobbies, Family?

I grew up in the suburbs of the Twin Cities of Minnesota with family roots in northwestern Wisconsin. After formative years in Minnesota came graduate school in Michigan, semiconductor research with Motorola, Inc. in Arizona, and the last 20 years in the Keweenaw as faculty. I have too many hobbies and acquired skills outside of my profession, but they mostly revolve around musical enjoyment and performance, or enjoying and utilizing the northern forest and timber, or both. My wife calls me an “ent” (one of those mythical tree creatures who move and talk in the Lord of the Rings).

Tom, how did you find engineering?

I started getting interested way back in grade school when I learned that you can make electromagnets with a lantern battery, a nail, and some wire. Later, in high school, my part time job was at a family owned electronics shop. I loved working with customers to help solve their problems. This was back in the day of mobile phones being “bag phones” and then I saw the transition to smaller phones. I remember being blown away by the Motorola Startac flip phone. When I graduated high school, I wanted to take the next step and learn more about how such cool devices work and how they are made.

Hobbies and Interests?

I was born and raised in Ashland, Wisconsin. My parents still live in the house I grew up in. I enjoy playing trombone, hunting, fishing, woodworking, and language learning. I met my wife, Jin, at Michigan Tech. She earned her PhD in electrical engineering at Michigan Tech, advised by Dr. Bergstrom. Our two sons, now aged 10 and 12, know all the technical jargon and acronyms. They talk about “SOP” (Standard Operating Procedure) while doing the dishes, and BKM (Best Known Method) while putting them away!