Linday Hiltunen shares her knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive Zoom webinar this Monday, January 24 at 6 pm ET. Learn something new in just 30 minutes (or so), with time after for Q&A! Get the full scoop and register at mtu.edu/huskybites.

What are you doing for supper this Monday night 1/24 at 6 ET? Grab a bite with Dean Janet Callahan and Lindsay Hiltunen, Michigan Tech’s University Archivist.

During Husky Bites Hiltunen will share the history of Winter Carnival, one of Michigan Tech’s most beloved traditions across the decades, through rich images of fun and festivities via the Michigan Tech Archives–from queens to cookouts, snow statues to snowballs, skating reviews to dog sled races, and more. Michigan Tech’s legendary Winter Carnival will take place this year for the 100th time February 9–12, 2022.

Joining in will be mechanical engineering alumna Cynthia Hodges, who serves as a Wikipedian in Residence (WiR) for Michigan Tech. To celebrate the 100th anniversary, Hodges is organizing a Winter Carnival Wikipedia Edit-a-thon, and alumni and students are welcome to help. (Find out how at the end of this blog).

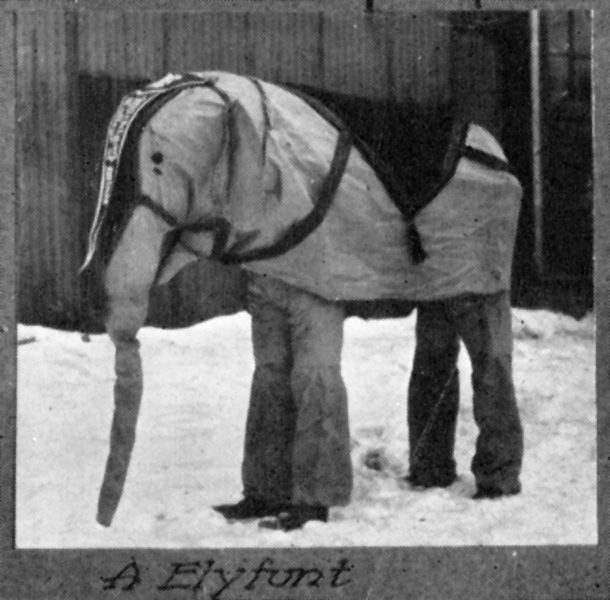

Ice Carnival Elyfunt, circa 1924. Source: Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections

It all began back in 1922, when a student organization presented a one-night Ice Carnival. The show consisted of circus-style acts, with students dressed up in animal costumes, bands playing, and speed and figure-skating contests. Twelve years later, in 1934, students in Michigan Tech’s Blue Key National Honor Society began organizing the event, changing the name from “Ice Carnival” to “Winter Carnival”. Students and local school children built their first snow statues that year, and the tradition grew. So did the statues, becoming bigger and more elaborate with each passing year.

Hiltunen is a Michigan Tech alumna and current PhD student with two master’s degrees in library science and United States history. She’s a trustee to the Historical Society of Michigan’s Board of Directors, chair of the Society of American Archivists Oral History Section, and vice president-president elect of the Michigan Archival Association (she’ll become MAA president in June 2022).

Lindsay, how did you first get involved in library science? What sparked your interest?

I’ve had an interest in libraries and history since a young age. My grandfather was a history professor at Michigan Tech and the first lay president at what is now Finlandia University. The sunroom at my grandparents’ house on Summit Street was my favorite place; one wall of windows and three walls of history books from floor to ceiling. Anytime I was there to visit I would steal away to the sunroom and read and dream for hours. It wasn’t until I attended Michigan Tech as an undergrad and obtained student employment in the archives (then on the 3rd floor of the library) that I knew what an archivist did. I credit my grandpa for the spark and former university archivist, Erik Nordberg for showing me the path to library school.

My library career fully began at the District of Columbia Public Library as a library technician. I became an archivist at Michigan Tech in 2014, and University Archivist in May 2016. As a side note, I’m proud to say I’m now the steward of my grandpa Dave’s impressive book collection.

Hometown and family?

I grew up in Tamarack City and graduated from Dollar Bay High School. My mom was an avid artist and my dad is the former director of a local social services coordinating agency. I have two brothers and one sister; all but one of us are Huskies. (The one who didn’t go to Michigan Tech has two husky dogs as pets, so that counts for something.)

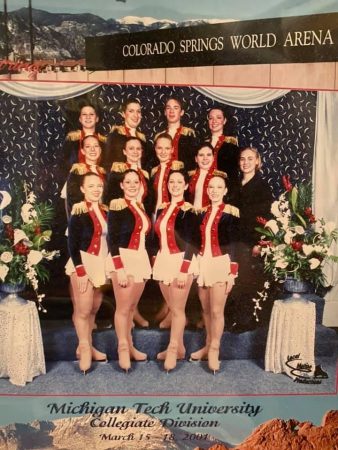

We grew up playing every sport under the sun. Those sports we didn’t play, we were spectators of, took books and stats, or ran the clock. In the SDC ice rink and Dee stadium I was a competitive figure skater (ice dancing and synchronized skating) and coach. Off-ice practice was just as good because we got to watch the MTU hockey players practice, then attend games with dad and grandpa.

I’m also proud to note that my husband of 17 years, Tom, is a Michigan Tech alum (EE 2005.) He now works as a Primary Patent Examiner for the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

My vinyl collection has been a passion since I was a teenager. I have over 5,000 LPs and I’m on the lookout for new records all the time. I love to read for my PhD program and also for fun, so nine times out of ten there is a book within an arm’s reach. Painting and drawing bring me a lot of peace. And I have three pets: A blue point Siamese cat, Little Nero, and two Weimaraners, Otto and Frankenstein. Our home on Keweenaw Bay also has many resident critters, including Swift the fox who runs by nightly, a few bald eagles that troll the shoreline, and many chickadees, finches, jays, and cardinals at our garden feeders. I consider them all friends!

Cynthia, how did you first get involved in engineering? What sparked your interest?

I received a scholarship to attend Women In Engineering at Michigan Tech in the summer of 1981 when I was a junior in high school, through Michigan Tech’s Summer Youth Program. At that time, it was one of the few programs of its kind to encourage women to study engineering.

After graduating with my BS and MS in Mechanical Engineering, I began a 32-year career at Ford Motor Company, working as a product test engineer in their durability engineering laboratory. I spent much of my career at Ford involved in chassis engineering, designing fuel and steering systems, suspension, tires, wheels, and brakes for many Ford cars and trucks.

Family and hometown?

My hometown is Warren, Michigan. My husband, Andrew Hodges, earned a BS in Civil Engineering at Michigan Tech in 1989. My son, Edward, is also an alum–he earned his BS in Forestry in 2019. My daughter, Jane, is a graphic designer. We tried to convince her to go to Michigan Tech as well, but there is no Bachelor of Fine Arts program. She went to Eastern Michigan University.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I love to cook, sew, read and sing, and enjoy the outdoors in the Keweenaw—especially skiing, mountain biking, and hiking.

How did you and Lindsay become friends?

That is interesting! We started out as facebook friends, because we have a lot of friends in common. I only met her in real life recently, but have admired her work for a long time. I really like history and enjoy visiting the Michigan Tech archives to research old recipes for my food blog, motherskitchen.blogspot.com.

A few years ago Lindsay did an excellent presentation about the history of women at Michigan Tech for the Presidential Council of Alumnae. I am happy to count her as a friend, and excited to work on projects with her, too.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of Winter Carnival, we will be improving Michigan Tech Winter Carnival information on Wikipedia. Alumni and students are welcome to help. If you are interested, please contact me at chodges@mtu.edu.

Read more

History—and Awards—Run in the Family

Michigan Tech Archivists Preserve the Past for the Future

Ford Motor Company Donates Support for Women in Engineering Scholarships