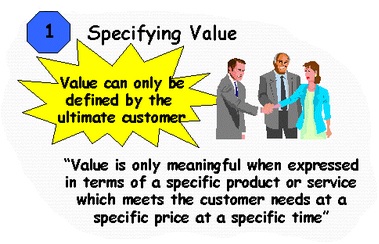

At the heart of Lean is a focus on the customer and a spirit of continuous improvement. In this post, I want to discuss the concept of customer value.

Many people think they have a firm grasp on the concept of value, but in reality understanding how value is created, applied, measured, and translated is a difficult task. This is because each and every person has their own perception of what constitutes value and this belief of what value is changes over time. Though it may prove difficult, identifying what creates value for the customer is the very first principle of Lean; it’s a task that must be completed before beginning any process improvement efforts.

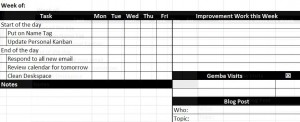

Upon the completion of this task, not only will you know what your customers value, you’ll also have a basis for defining your day-to-day activities. Having that level of definition will help answer 3 important questions:

- What should I be doing?

- How should I be doing it?

- Why should I be doing it?

Everything we do on a daily basis, no matter how small, should create some kind of value for our specific customers. Defining said value forms the foundation upon which you build Lean processes to deliver that value and satisfy your customer. For an activity to be value added, you must meet all three precise criteria:

- The customer must be willing to pay for the activity.

- The activity must transform the product or service in some way.

- The activity must be done correctly the first time.

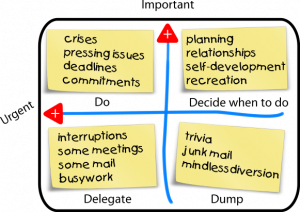

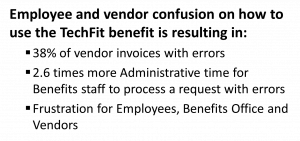

If an activity does not meet all three value-added criteria, then it’s deemed officially to be non-value-added. In Lean, non-value-added activities are further broken down into two types of muda (or waste):

- Type-1 waste includes actions that are non-value-added, but are required for some other reason. These are typically support activities that allow those critical value-added activities to take place. These forms of waste usually cannot be eliminated immediately.

- Type-2 wastes are those activities that are non-value-added and are unnecessary. These activities are the first targets for elimination.

Many activities may seem as though they’re necessary or value-added, but on closer examination, viewing them through the eyes of the customer, they’re not. For example, if you are completing paperwork to pass on to another department, or creating reports for your supervisor, the first order of business should always be to define what information is of value to the person receiving the documents you’re creating. You may find that a portion of the information you’re collecting or reporting is of no value to your “customer,” and therefore collecting and documenting that information only serves to create waste in the process.

Identifying customer value and seeking out and eliminating waste takes effort — it’s a journey that begins with challenging the status quo. If you’re ready to accept this challenge and begin your journey, call the Office of Continuous Improvement at 906-487-3180 or email us at involvement@mtu.edu. We will work with you and give you the tools you need to get you headed in the right direction.