For some students pursuing technological careers, the world of art might feel foreign and intimidating. In her Art and Flora course, Visual and Performing Arts Professor Anne Beffel encourages students to be as comfortable experimenting in the studio as they are in the lab.

“Setting the stage for students to know their own sense of aesthetic is one of the most important things I can do so that when they leave this class they are making work that is relevant to them and how they view the world rather than following a prescribed path,” said Beffel.

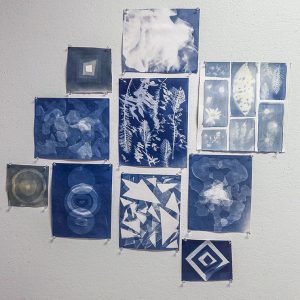

Students in her most recent class experimented with sun prints and natural inks—two techniques not commonly combined in the art world. They were first introduced to sun prints, also referred to as cyanotypes for their bright-blue appearance. Sun printing involves painting an emulsion on a material such as paper. Artists then place an object with some degree of opacity on the material to block the sunlight. Everything on the material that’s exposed to the sun turns blue due to a chemical reaction. The longer the exposure, the darker the blue. The artist stops the reaction by removing the material from sunlight and rinsing off the reactive chemicals.

“I’m most concerned about students finding out about who they are.”

While students were working with cyanotyping, Beffel also introduced them to methods for creating their own natural inks. The class gathered elderberries near the Walker Arts and Humanities building, wood charcoal from fire pits along the campus beach at Prince’s Point, and even bricks from their driveways.

The activity was eye-opening.

“I think something that happened for all of us in this process was that we started looking at the material world differently,” said Beffel.

Sound design student Evan Meyer, ’26, found a new perspective right outside his home. “I was walking down my driveway and I saw the brick out of the corner of my eye and thought, ‘That is a cool color. I wonder if I can get that into an ink’,” he said.

Students tried many different methods to create inks, grinding materials between a glass plate and muller to create a fine dust that would float in water or whatever liquid medium each student selected to make the ink stick to paper. Meyer mulled charcoal for about two hours to get a very dark black ink. Beffel said it’s one of the most difficult colors to produce. Other students boiled various fruits and plant matter for their inks, or extracted pigments with alcohol.

“The boiling process breaks down some of the pigments in different fruits,” said computer science student Marissa Burgess ’26, “so, I experimented with boiling blueberries and blackberries, and then I put some in isopropyl alcohol which extracts the pigments without breaking them down.”

The techniques are not new. Natural inks have been used for centuries by artists and textile artisans. Cyanotypes have been used by naturalists to record plant varieties since the 1800s and are the reason plans are called “blueprints” in the construction and design fields. What is unique about Beffel’s class is how they chose to combine the two techniques. Collectively and of their own spontaneous creativity, the class began adding natural inks to their sun prints.

“I feel like it kind of just went together because we were in that experimentation phase,” said electrical engineering student Harley Russell ’26, “It was like a group concept and then we each went our own directions with it.”

Several students in Anne Beffel’s class dove into combining natural ink with cyanotypes,

including Olivia Thompson ’27 and Harley Russell ’26.

Select any photo to view the full gallery.

“Oftentimes in these classes I teach, the techniques are very direct and immediate but you can go very deep with subtle changes and experiment. It brings you in relationship with the material and the more you spend time with it the more it mirrors who you are as a person,” said Beffel.

Each student had their own way of approaching the process. Some were spontaneous while others were methodical, even looking at samples of their inks under the Hitachi TM4000 Plus Scanning Electron Microscope available at Michigan Tech’s Applied Chemical and Morphological Analysis Laboratory to get a new perspective on the materials they worked with.

Mechanical engineering student Olivia Thompson, ’27, let her cyanotype paper sit in a tub of natural dye for different amounts of time to get color variations on the formerly white space of her sun print. Kayleigh Mattson, ’28, who is still exploring options for her major, incorporated shapes and patterns she found intriguing from one of her math classes.

Thompson and other students also experimented with changing their ink colors by using baking soda to adjust the pH. They also discovered several alcohol inks that changed color as they dried. For example, orange rose hips would dry yellow and purple inks dried green, changing the coloration and composition of art pieces.

For some students, the greatest discovery was that not every technique helped with what their art was trying to express.

Mallory Grant ’27 learned that she preferred to keep the processes separate. “At the end of it all I really liked the vibrant blue of the cyanotype without the ink,” said the computer engineering student. “Everyone has their own preference.”

“It is preference,” Beffel said. “But it is a preference informed by experience.”

Whatever methods students chose, bravery and curiosity were clear in their art as they explored and experimented. Unexpected or even unwanted outcomes were a learning experience.

“I couldn’t think of a better student population to work with because they are out in the world, thinking and doing, and they bring that into these art classes with a really open sense of what is possible and what we can call art,” said Beffel.

About the College of Sciences and Arts

The College of Sciences and Arts is a global center of academic excellence in the sciences, humanities, and arts for a technological world. Our teacher-scholar model is a foundation for experiential learning, innovative research and scholarship, and civic leadership. The College offers 33 bachelor’s degrees in biological sciences, chemistry, humanities, kinesiology and Integrative physiology, mathematical sciences, physics, psychology and human factors, social sciences, and visual and performing arts. We are home to Michigan Tech’s pre-health professions and ROTC programs. The College offers 24 graduate degrees and certificates. We conduct approximately $12 million in externally funded research in health and wellness, sustainability and resiliency, and the human-technology frontier.

Follow the College on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, X and the CSA blog. Questions? Contact us at csa@mtu.edu.