There’s a new way to reach out to connect about sustainability at Michigan Tech! You can contact sustainability@mtu.edu to share ideas, ask questions, and get in touch with campus leaders focused on sustainability.

This story was originally shared in Tech Today on May 24th 2021, by Alan Turnquist, Tech Forward Initiative on Sustainability and Resilience. Please see Tech Today for the full story.

The first ever Husky Exchange Program collected over 3,000 items from students moving out of the residence halls this spring!

The Exchange Program successfully diverted over 2,000 pounds of waste from the landfill, and more than 1,000 of these items have already been donated to local food pantries and charities.

Remaining items will be donated or sold to students moving into the residence halls in August. Any funds raised will be used to seed a student “green fund” that will be used to promote future student-led sustainability efforts on campus.

A special thanks to the more than 20 volunteers who made this possible!

Extra thanks to Alan Turnquist for initiating the Exchange Program and to the Tech Forward Initiative on Sustainability & Resilience for its support.

Reposted from Tech Today

When Michigan Tech was first established, the surrounding wilderness was rapidly changing into an industrial center. Copper mining and the timber industry were providing natural resources for use across the nation. Just as this legacy of industrial growth and its structures tie us to our past, the trees on our campus connect our University to the outlying landscape and the wilderness from which it grew.

The trees on our campus provide a sense of place, natural history, and are a reminder of our relationship with the land. Over the past several years the Department of Facilities Management has been working with a Campus Tree Advisory Committee to advance tree-related activities on campus. The Campus Tree Advisory Committee is comprised of faculty, staff, students and community members with an interest in sustainable planning, development, and education pertaining to tree care and the campus landscape.

For the second consecutive year, Michigan Tech was recognized by the Arbor Day Foundation as a Tree Campus Higher Education honoree. “The Tree Campus Higher Education program helps colleges and universities establish and sustain healthy community forests.” You can learn more about the Tree Campus Higher Education program here. Michigan Tech is one of four public universities in Michigan to be recognized for our efforts related to “promoting healthy trees and student involvement.”

The Campus Tree Advisory Committee is currently planning for another year of activities on campus and in our surrounding communities. Student involvement will also be a priority this year with a goal of developing a larger group of interested and active volunteers. Annual events include an Arbor Day observance as well as service-learning projects that require inspired and motivated student volunteers. If you have an interest in becoming a part of the University’s Tree Campus organization please send an email to treecampus-l@mtu.edu and we’ll include you in future correspondence.

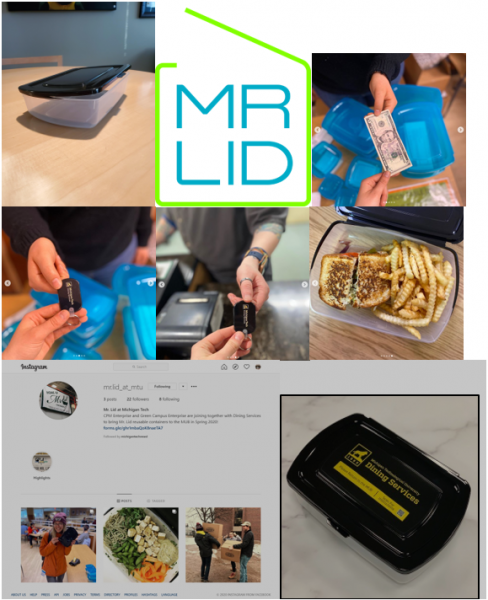

Michigan Tech Dining Services is partnering with Consumers Product Manufacturing to implement a returnable container program. CPM is working with the reusable container brand, Mr. Lid, to reduce campus waste associated with food. Together, we are implementing the use of these containers in the Memorial Union Building to reduce the amount of single-use plastics being thrown away.

This program is currently set to launch March 8, the week after Spring Break.

CPM members will be in the MUB most days during lunch hours to offer a chance to ask questions about the program or to buy in early. Once the program launches in the MUB, you will be able to buy in at the register.

For more questions, please contact CPM Student Karen Helppi, kjhelppi@mtu.edu

How it works:

- Buy into the program with a one-time $5 Program Fee

- Receive one of 50 program key-chains

- At the time of check-out for your food at the North Coast Cafe (MUB), you will hand the cashier the keychain.

- At this time, the cashier applies a 10% discount to your food.

- You receive in return, your food in a reusable container

- Once you are ready to return the container (this can be at any time), you hand the North Coast Cafe cashier the dirty container and receive your keychain in return.

- The returned Mr.Lid is washed and sanitized by the MUB’s commercial dishwashers to be reused.

- Repeat steps 3-5 for the rest of your collegiate career!

Michigan Tech is hiring a university Director of Sustainability and Resilience! The detailed job posting is available here. This is a very important position for Michigan Tech, and a very important step in the right direction for the University. I hope you’ll share this job announcement with anyone who may be interested, and I hope Michigan Tech finds and hires an innovative, passionate, and forward thinking professional to meet the unmet needs on campus in coordinating and providing long term, strategic vision for sustainability and resilience. Tomorrow needs Michigan Tech because tomorrow requires sustainability and resilience thinking, and here’s hoping this new position means Michigan Tech is ready to be proactive about planning for and participating in a more sustainable and resilient future!

This material was provided by Dan Liebau, an MTU facilities site engineer, and was originally published in Tech Today on December 14th 2020.

Anchored by the Sustainability and Resilience Tech Forward initiative, Michigan Tech continues to develop its sustainable practices on campus. Campus recycling efforts can be measured by our waste diversion rate. The waste diversion rate is the ratio of recycled material to the total weight of campus’ solid waste stream. Currently, the University has a solid waste diversion rate goal of 18%.

The monthly diversion rate for November was 18.93%. Since the beginning of the fiscal year, (July 2020) our overall solid waste diversion rate is 12.49%. By comparison, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) reported a statewide estimated recycling rate of 18.1% in 2018 – up from 15% in 2015.The intent of sharing campus waste diversion rate information is to educate our community on campus recycling initiatives and increase participation in our current recycling programs.

There’s still work to be done, and this is where you as a community member can help. Making a conscious choice to recycle not only improves the University’s waste diversion rate, it also reduces costs associated with solid waste management on campus. Participation also assists in further developing our current recycling programs and better aligning Michigan Tech with EGLE’s goals of achieving a statewide recycling rate of 45%.

Additional information and updates related to campus sustainability initiatives can be found at mtu.edu/sustainability.

“Sustainability” is most conventionally defined as the ability to meet the needs of current generations without jeopardizing the ability of future generations to also meet their own needs. This definition was popularized in the Brundtland Report. It assumed that balance could be achieved by considering long term impacts across three dimensions: social, economic, and ecological. More recent definitions of “strong sustainability” embed these three dimensions within one another, as concentric circles rather than a Venn diagram, recognizing that economic systems should operate to support social wellbeing and that both social life and economies ultimately depend on ecological systems.

One immediate question we can ask about the conventional definition of sustainability is: are we meeting the needs of current generations? Globally, the answer is clearly no; we live in a world rife with poverty, unnecessary malnutrition and starvation, and death from preventable disease. Narrowing our gaze to the United States, the answer is also clearly no; events throughout the summer of 2020 highlighted the continued violence, including systemic and structural violence committed by the very institutions intended to uphold law and order and justice, towards people who are Black (and Indigenous and People of Color, hereafter abbreviated BIPOC) in America. People who have historically been marginalized and oppressed by centuries of settler colonialism, genocide, slavery, and segregation in America continue to have unmet physical, economic, and social needs including safety, wellbeing, and inclusion.

There is another way to think about this word and concept “sustainability” – we can ask ourselves, is this system as it exists sustainable, meaning can it continue to exist in the long term (like seven generations)? The systems of violence and oppression based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, and ability are not sustainable. They are quite literally tearing our country apart, as we become an increasingly polarized, increasingly violent, and increasingly unsafe nation, for BIPOC and everyone else who cares about the rights to safety from physical harm and justice through institutional process shared by every human on earth.

Finally, we can also ask, is Michigan Tech as an institution sustainable? Is its ability to respond in meaningful ways to current events, to make itself relevant to its students and the social world, supporting its ability to sustain itself as an institution of higher education? The answer is definitely and absolutely no.

Michigan Tech has failed to provide any kind of institutional response denouncing white supremacy (even when it is right here on campus) and continues to fail to provide support for BIPOC students who are categorically less safe than their white student counterparts. Every BIPOC student I work with has experienced hate in this community, sometimes at the hands of the police. Every time this is brought to the attention of Michigan Tech administrators, they respond as if they’re shocked by some isolated incident of hate rather than treating reality as it is: we live in a society that is systematically racist and oppressive to BIPOC, and it is the obligation of an institution of higher education to acknowledge empirical realities and educate their students about them.

An event at a recent University Senate meeting makes this lack of sustainability perfectly clear (start at 1:45). When a student read a thoughtful, heart wrenching open letter about how hurtful and damaging it is that the University continues to remain silent about these issues, the most senior administrator in the room asked for, of all things, a minute of silence! With a student imploring them to stop being silent, University administration literally responded with more silence.

BIPOC students at Michigan Tech know that this is an emotionally and physically unsafe place to learn. It will be impossible for Tech to increase the diversity of students on campus without addressing this reality as a systemic, structural issue. Michigan Tech is making itself irrelevant, and therefore unsustainable, in the world of higher education.

As you’ll hear if you listen to the end of the University Senate meeting, there are faculty on campus who care deeply about seeing structural changes that will better support BIPOC students. As a member of the Department of Social Sciences, I’ve been collaborating with a group of faculty and students since summer 2020 to develop a shared statement and list of commitments to action we can take at a Department level to address systematic oppression and systems of violence that harm BIPOC students, faculty, and staff at Michigan Tech. The University administration has told my Department that, although no written policy exists, we are not allowed to post that statement on the Department’s website, lest it be confused for an official university statement (which only the Board of Trustees is allowed to make). So, let me be unequivocally clear that this writing represents my perspective as a social scientist, a scientific expert in understanding social life. It is my professional opinion, but mine alone and not representative of anyone at Michigan Tech, that Black Lives Matter, that BIPOC students are not being supported in the ways they deserve, and that our University’s non-response is one indication that this University is not sustainable.

There is a newly formed Michigan Tech chapter of the Climate Reality Campus Corps, a national movement of University campuses associated with the Climate Reality Project. The student leaders of the Michigan Tech chapter recently hosted a 24 Hours of Reality event explaining the science, impacts, and solutions of the climate crisis while also highlighting how Michigan Tech fits into the bigger picture. The video of that presentation is now available for anyone to watch here. The Michigan Tech Climate Reality Campus Corps is asking Michigan Tech to start planning for a transition to 100% renewable energy for campus electricity. Michigan Tech can demonstrate its leadership in sustainability and resilience through this commitment, and student leaders on campus are ready to have conversations about making this campaign a reality!

Are you interested in how Michigan Tech gets, uses and saves energy? If so, stop by the Sustainability Stewards meeting on Wednesday, October 21st at 8pm to see information from the Energy Pie-Chart, the 50% commitment to wind, alternative energy on campus, and easy ways you can reduce your energy footprint today.

Guest speakers include: Larry Hermanson from Facilities Management, Jay Meldrum from the Keweenaw Research Center, Rose Turner from the Sustainability Demonstration House, and Kendra Lachcik from the Campus Corps.

You can join the meeting via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/9499596761

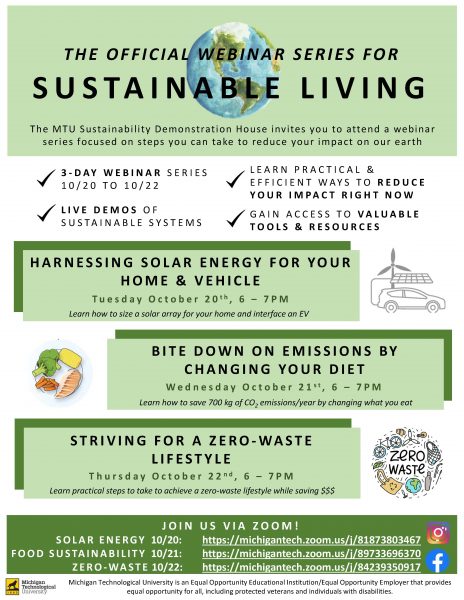

Since the MTU Sustainability Demonstration House (SDH) is limited in opening the house and its activities to the public this semester, SDH is bringing the house and all of its sustainable systems to virtual viewers!

You are invited to join MTU SDH for a series of webinars centered around various aspects of sustainable living:

Tuesday, October 20th: Harnessing Solar Energy for Your Home & Vehicle Learn how to size a solar array for your home!

Join via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/81873803467

Wednesday, October 21st: Bite Down on Emissions by Changing Your Diet Learn how to save 700 kg of CO2 emissions per year by changing what you eat!

Join via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/89733696370

Thursday, October 22nd: Striving for a Zero-Waste Lifestyle Learn practical steps to take to achieve a zero-waste lifestyle while saving $$$!

Join via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/84239350917

You won’t want to miss out on these talks!

- View live demos of the MTU SDH sustainable systems

- Gain access to valuable tools & resources

- Learn practical and efficient ways to reduce your impact right now

Please email sdh@mtu.edu with any questions or concerns. We hope to see you there!