This is a guest post from Dante Paglia, who is a fourth year computer science undergraduate at Michigan Tech. He can be reached at dfpaglia@mtu.edu

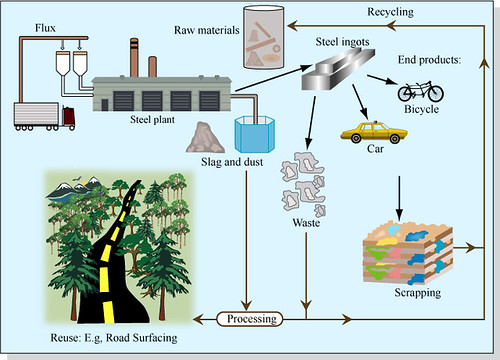

Life cycle assessment, also known as life cycle analysis, is used to assess environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product’s life. The stages include the collection of the raw materials, processing those materials, manufacturing the product, distribution via various transportation techniques, use of the product as well as the repair, disposal and recycling during the products end of life. This kind of assessment is used by companies and product designers to better understand their products impacts, discover where the product can be improved, and work toward implementing those improvements. Below is a visual of the stages of a products life that are looked at during a life cycle analysis.

There are four main phases of a life cycle analysis. The first phase is the goal and scope. This sets the outline of the study and depicts the format of the results as well as who will receive the results of the assessment. The second stage is the life cycle inventory. In this stage the inventory flow of inputs for a product are recorded. Examples of inventory flows include, water, energy, raw materials and waste releases to either land, air or water. In this step, all of the inputs and outputs that are used or created during the products life are recorded. The third stage of a life cycle assessment is the actual impact assessment. The data gathered in the previous step is sorted and assigned impact categories to help weigh the impact the product has on the environment. Lastly, interpretation is done. The information from the results of the analysis must be checked and evaluated. In other words, the results of phases two and three are summarized in the interpretation phase. The completed assessment is then reviewed to understand the impacts of the product and to see where improvements can be made to lessen the overall impact on the environment.

Life cycle analyses are a widely popular tool to increase a company’s sustainability. This is because the analysis usually includes information that fits into all three pillars of sustainability. While the overall goal of the assessment is to review environmental impacts, social and economic impacts are considered as well. You can learn more about the three pillars of sustainability by clicking here.

There are many variants of a life cycle assessment where different stages of a products life are analyzed. The three most common kinds are cradle to gate, cradle to grave, and cradle to cradle. Cradle to gate only looks at a product when it is in the hands of the producer, once it leaves the factory its impacts are no longer considered. Cradle to grave takes it a step further and follows a product from the very beginning all the way until it is disposed of. Lastly, cradle to cradle takes things even further and instead of disposal of the product, it is recycled and reused in the process again. Often a cradle to cradle design leads to the least amount of environmental impact. One example of cradle to cradle is discarded asphalt pavement being reused to create new pavement. Below is a graphic showing another example of cradle to cradle design with steel production. This shows how everything, including the waste bi-products of steel production can be used for something useful or simply recycled back into the steel making process.

Photo from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/mitopencourseware/3247853726

An example of the use of life cycle analysis is the U.S. Department of Energy produced report that shows the energy and environmental benefits of LED lights over incandescent and fluorescent lights. LED lights proved to be more energy efficient and less harmful to the environment to produce as well as transport than both other kinds. This led to a rise in popularity of LED lights hence providing an overall benefit of large energy savings and significantly less environmental harm. The full study can be found by following this link.

Additionally, life cycle assessment is something that many solar panel producing companies are required to do and have planned out prior to receiving funding from the government. Since solar panels include hazardous materials like cadmium and cadmium compounds, it is not only important to make sure that the raw resources are being retrieved in a safe manner but the end of life of the products needs to be taken into account. If a solar panel is to be disposed of for any reason, whether it be because it broke during production or it is no longer being used or is being replaced, companies need to make sure that their product with these hazardous chemicals is properly disposed of. This means it cannot be tossed into landfills but needs to be recycled in a manner where the harmful compounds are disposed of properly or reused for new solar panels. This article on solar panel recycling explains some of the options there are for safe disposal of unwanted or old panels. A life cycle assessment helps find issues in these stages and brings them to the attention of the product’s producers allowing them to change their ways.

Life cycle assessment is an important concept to be aware of because every company should be doing some variant of a life cycle analysis for their products. Not every company needs to do cradle to cradle analysis, but they should assess their production in some way. By doing so they can discover issues in their production cycle as well as make improvements to make their product better in terms of energy and environmental harm. With this, their product and company as a whole will become more sustainable and attractive to the large number of investors and customers who are paying closer and closer attention to companies sustainability policies. Most importantly in modern day, the end of life portion of production needs to be analyzed and understood so companies can mitigate the environmental impact their product does. The more recycling options that can be found for products the better to reduce the amounts ending up in landfills causing more harm with their pollution than good they provided overall. Without these kinds of analysis, companies would be able to do whatever is the most cost effective in production, which almost never coincides with sustainability and being environmentally friendly.