The shores, clad in perpetual verdure, rising upon the vision and receding in the distance, stir up the mind with their grandeur and mellow it with their beauty, creating an intense harmony that may be felt and enjoyed but cannot be described. There was the wildness of nature as it presents its rugged front as a barrier to the footsteps of all, conquering the art, and there too was the foothold art had made from which to take up her march… And now, when we know the richness, the fertility, the beauty, the hidden and the exposed wealth of the great Western and Northwestern country that is and must ever be tributary to this lake, we are more sanguine than ever of the growth of the new towns of Lake Superior (Bayfield 1858:14).

Since the beginning, the “big lake” and the vessels that ply her have been the primary facilitators of the Copper Country’s economic and cultural development during the nineteenth century. From the earliest voyageur canoes that brought early Keweenaw explorers to its shores to the palatial cruise vessels that offloaded scores of visitors to its docks middle-late in the nineteenth century, the Copper Country relied on the marine highway during its most important years.

Getting to the Keweenaw, however, was never as easy as “well, send a boat”. As the region experienced economic ebbs and flow, so too did the demand for lake boats. The passenger/package freight propeller was one such vernacular craft that embodied the economic and social needs of the Copper Country in the middle nineteenth century. Often reduced to “package steamers”, “wooden steamers”, or “wooden propellers”, these vessels were Keweenaw’s quintessential multiple-purpose supply ship.

The Lake Superior passenger/package freight propeller was largely brought about by the 1855 completion of the Sault Locks that bypassed the rapids on the St. Mary’s River. As was the case with the Erie and Welland Canals, the physical dimensions of the Sault Locks dictated the size of the vessels that would pass through it. To no coincidence, ship builders were quickly contracted to build hulls specifically for the Lake Superior market. As the iron ore industry wouldn’t boom until some decades later, copper was the primary market for entrepreneurial fleet owners. JT Whiting was one owner of note who had begun acquiring vessel interests in anticipation of the Sault Locks’ opening.

By summer of 1855 Whiting controlled all steam-powered vessels on Lake Superior except four (Julia Palmer, Traveler, Sam Ward, and Manhattan). Nine years later, Whiting had interests in two-thirds of maritime commerce on Lake Superior including regular visitors Meteor and Pewabic: the flagships of Whiting’s Pioneer Lake Superior Line. These passenger/package freight propellers were built with an elegant first-class deck on top of the main deck that housed the package freight and steerage passengers.

The first-class accommodations of Pewabic and Meteor emulated the changing American social agenda and the emergence of the middle-class. Membership to this expanding American group was no longer restricted to the self-employed. Salaried employees of growing America in the late 1850s and 1860s began to use recreation, travel, and leisure to distinguish themselves from members of the working class (Aron 1999:93). Vessels like Pewabic and Meteor became an arena for this emerging social group to experiment with newly founded middle class behaviors like flirting, dancing, drinking, and jazz.

The staterooms were in two rows that ran bow to stern on each side of the vessels. They faced outboard to the lake and inboard to the central saloon that served as the dining room and dancing hall. These vessels made few stops on their way to the Great White North, and, besides swimming ashore, guests had no option but to partake in the daily dances, late-night parties, and social mingling.

Just twelve inches of white pine separated the first-class experience from steerage. In the enclosed main deck miners, labor contractors, and others traveling on the cheap were sprawled between the boxes, barrels, and bags of package freight that was also Houghton-bound. Fare was calculated by the mile, with no meals included, and most times steerage passengers were confined to the dark main deck. One can imagine the muffled conversations in different languages among the boats’ creaks and moans. Life downstairs was a staggeringly different experience than life upstairs.

It is without question that the iconic passenger/package freight propeller had tremendous impact on the survival and development of the Copper Country during the middle-late nineteenth century. Before the railroad, they were the sole means of bringing copper to market while returning with provisions, tourists, and fresh labor. Over the past few years I have focused on studying the years 1855-1880 through the proverbial porthole of these important craft.

The University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections at the J. Robert Van Pelt and John and Ruanne Opie Library at Michigan Technological University possess some incredible primary sources that have, and will continue to round out this study. During my recent visit I focused on three collections: the Roy Drier Collection, Keweenaw Historical Society Collection, and Earl Gagnon Photograph Collection. Ship invoices, smelter receipts, contemporary photographs, local store daybooks, and secondary recollections of Copper Country’s maritime heritage were among my favorite, and most revealing sources.

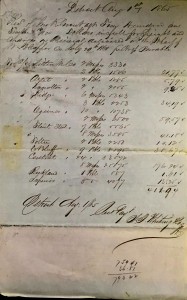

In one of the Keweenaw Historical Society Collection’s folders, I came across a receipt written by JT Whiting that acknowledges payment of $412 dollars from JR Grout for freight charges on float and barrel copper from Central, Rockland, and Superior mines as well as seven barrels of flint steel delivered by Pewabic to Detroit on August 1st, 1865. This document is significant for several reasons. First, it’s evident that in this case, and others from similar documents in the collection, that ship masters primarily dealt with agents from the smelters for both smelted material and mass copper transactions. This business model has implications that vessels could load most, if not all their downbound cargo at the smelter docks. Second, the receipt includes specific weight, freight charge, and container type for each cargo entry. This information sheds light on specific weight carried downbound, and possible main deck organization. Generally speaking: what did the main deck look like on a typical downbound trip from Houghton to Detroit. Third, this routine receipt was the last ever signed by JT Whiting for Pewabic.

Pewabic left Detroit the very next day for its seventh trip of the season, and on its return trip downbound collided with Meteor off Alpena, Michigan killing dozens and sending a valuable copper cargo to its final resting place, 165 feet beneath the surface. Even though this receipt is exactly that, a receipt, it’s value to my research in studying the maritime landscape of Copper Country is unmatched. Coupled with the hundreds of other primary sources I am still processing, my trip to the Archives was an incredible success. The data will be used in future papers, presentations at archaeology conferences, and to educate the public primarily through the Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center in Alpena which has a considerable collection of Pewabic artifacts and exhibits. It is an absolute pleasure to partner with Lindsay Hiltunen and the rest of the Archives staff to discover, explore, and reveal Copper Country’s maritime identity through primary source research. Feel free to contact me at phil.hartmeyer@noaa.gov with any questions or comments.

——————————————————————————————————

This is a guest blog post from visiting scholar Philip Hartmeyer, a maritime archaeologist with the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Alpena, Michigan. His research trip was made possible by the Michigan Tech Archives Travel Grant Program, which is generously funded by the Friends of the Michigan Tech Library.

Sources Cited

Aron, Cindy S. 1999, Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Bayfield City 1858, Bayfield, Lake Superior: Early History, Situation, Harbor, Ocean Commerce, Mineral & Agricultural Resources, Rail Roads, Stage Roads, Lumber, Fisheries, Climate of Lake Superior, Pre-Emption Lands, Invitation to Settlers: An Account Of A Pleasure Tour to Lake Superior. Philadelphia, PA.