View of Copper Harbor from Brockway Mountain, May 2015. Photograph by the author.

Almost everyone who has visited the Keweenaw Peninsula has heard the name Brockway. Brockway Mountain, just west of Copper Harbor, offers a stunning panorama of Lake Superior, a smattering of nearby lakes, and the thickly-forested rolling hills among which Michigan’s northernmost town is nestled. In addition to its scenic roadway–a project that put local men to work during the Great Depression–the mountain enjoys another notable tie to history, having been named after early settler Daniel Brockway. After a sojourn in L’Anse as a government-employed blacksmith and mechanic, Brockway had come to the Copper Harbor area in the mid-1840s. There, and in later years at the Cliff Mine, Brockway was a prominent merchant, hotelier, and mine agent.

Yet Daniel Brockway’s laudable success in the Copper Country is only one part of the story. From the Brockway family tree sprouted a number of remarkable people, both in terms of careers and of character. Although Women’s History Month is just behind us, it is well worth keeping our eyes on women’s history; let us take a moment to “remember the ladies,” as Abigail Adams once said. While a single blog post could never do justice to their stories, we are privileged to be able to share a glimpse of what we see of the Brockway women through our collections at the Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections.

Lucena Harris Brockway, the matriarch, left the greatest archival trail. Diaries she kept meticulously for some thirty years now reside in the Michigan Tech Archives, recording her life in her own words and shedding light on the interesting experiences of others in her family. What we see from Lucena’s writing are women who confronted the challenges of ordinary days, the heartbreaking difficulty of tragedies, and the world at large with courage, humor, strength, and flair. We’ll start with Lucena herself, then look down her familial line to see her spirit carried on.

Lucena Harris Brockway in middle age. From MS-019: Brockway Photograph Collection.

Lucena, born in New York in 1816, moved to southwest Michigan in her youth and there married Daniel Brockway in 1836. She became the mother of four daughters and two sons, one of whom died in infancy and whose birthday was remembered with mournful devotion in her diaries. With her husband, Lucena made the aforementioned transition to the various locales of the Upper Peninsula and there dedicated herself to carving out a new life from the rugged locale. Though her husband’s growing financial assets meant that Lucena was insulated from some of life’s difficulties, living in a frontier community nevertheless required her to confront thorny dilemmas with tenacious resolution. At times, those problems bordered on the absurd. In August 1880, for example, Lucena awoke to an empty house and headed to her kitchen in hopes of having “a quiet day, the first in a long time.” When she glanced out the window, however, she found that her dreams of relaxation had quite literally gone up in smoke. The wooden fence near the Brockway home had spontaneously combusted and was now engulfed in flames. “So I fought fire for sometime [sic],” Lucena wrote, recalling the event later in the day, “then ate my breakfast and the fire had broken out again.” Eventually, her persistence in firefighting paid off, and the blaze came under control. Little time remained for resting by this point, however. There were chickens to be fed and beans to be picked for dinner. Life went on.

Life also had its lighthearted moments for Lucena. Removed as we are from the past, and accustomed to seeing the staid faces that early photography–with the long exposure times required to capture an image–produced, it is only too tempting to think of the 1800s as a stuffy, humorless age. Lucena Brockway was quite the opposite. In the cash account pages of her 1880 diary, she jotted a few puns that must have especially tickled her funny bone. “Why are hot rolls like caterpillars?” one read. “Because they make the butter fly.” Other jokes poked fun in a way that seems very modern. “Why is a lawyer like a restless sleeper?” Lucena asked. “He lies first on one side and then on the other.” There’s a certain humor not only in the joke but in realizing that attorneys have been the subject of light-hearted derision for centuries.

Charlotte Brockway, Lucena’s oldest daughter, left fewer clues to her life, but what can be pieced together from the archival record indicates that she was a woman fashioned in her mother’s mold. By the time she was five, she had moved with her parents from New York to the western Lower Peninsula, north to L’Anse, and from L’Anse to Copper Harbor. The realization that the last relocation included Charlotte’s two younger sisters–a toddler and an infant–speaks once again to her mother’s fortitude. At the tender age of fifteen, according to one source, Charlotte was bright and mature enough to teach the Copper Harbor school. In October 1863, the twenty-two-year-old married Oliver Atkins Farwell, the superintendent of the Phoenix Mine. Mr. Farwell, as Lucena always called him in her diaries, was in his early fifties. Despite the considerable difference in their ages, the marriage seems to have been affectionate, if not passionate: eleven children were born to Charlotte and her husband, including a set of twins.

Charlotte Brockway Farwell in her later years. From MS-019: Brockway Photograph Collection.

June 1881, as revealed in Lucena’s diaries, demonstrated the determination of the Brockway women to carry on in the face of great tragedy, and Charlotte was at the very heart of it. First, Sarah (“Sallie” or “Sally”) Brockway Scott lost her husband to illness; he was only 43. “Poor Scott breathed his last a quarter to three o’clock this morning,” wrote Lucena sadly on June 7. “…He knew he was going and bade us all good by [sic]. It was hard to see him go[;] he wanted to live longer if it had been so he could.” Sallie, who had already seen a daughter die in infancy, was now the widowed mother of a young son. Yet Charlotte would face an even more turbulent month. On June 18, Lucena noted that Oliver Farwell, who had begun feeling ill around the same time as Sally’s husband, was not improving. Three days later, the same note: “Mr. Farwell was worse and probably dying.” On June 22, Lucena said, “I stayed all day at Mr. Farwell’s with Charlotte. Mr. Oliver A. Farwell died 20 minutes past 3 o’clock P.M.” And, on June 25: “In the afternoon…Charlotte Farwell had a daughter born the day after her husband was buried.”

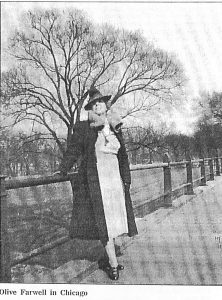

A photograph of Olive Farwell published in the Daily Mining Gazette in January 1997. From the Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections Farwell biographical file.

This daughter, named Olive Lucena in honor of her father and grandmother, would experience a life of great length and variety, testifying to the fortitude and courage of the Brockway women. She might not have achieved the fame of her brother, a notable librarian and botanist, but Olive carved her own niche. Her mother moved the family many times in Olive’s childhood, attempting to give her children the best life possible. From Keweenaw County, they headed south to Ypsilanti for educational reasons, then west to New Mexico in pursuit of a healthful climate. After a brief return to Lake Linden with her mother to spend time with Lucena and Daniel in their last days, Olive departed for Chicago to study interior design. Unsurprisingly, she made a success of it and established a studio in Spokane with another artist. Later, her obituary recalled, she returned to Chicago, first to work for a chain of department stores and then to establish her own prosperous candy kitchen. When World War II broke out, Olive again left Lake Linden–where she had moved in 1935–to become a Rosie the Riveter on a Lockheed production line in Burbank.

Lucena and Charlotte each lived to be 82. Olive surpassed them both, suffering a fatal stroke in the Brockway house in Lake Linden at the age of 98. Though these Brockway lives can hardly be compressed with any justice into an essay of such brevity, Lucena’s wide range of diaries–together with two other Brockway collections and articles clipped from the Daily Mining Gazette on Olive’s long life–show their shared character, spunk, and persistence. If you’d like to investigate the Brockway women further, or if you’re interested in discovering some remarkable women from your own family tree, please do not hesitate to contact the Michigan Tech Archives at copper@mtu.edu or (906) 487-2505.

And Anna Medora Brockway Gray, Lucena’s youngest daughter, who struck out on her own as a physician in 1883? Well, that’s another story for another day.