Thanks to singer Gordon Lightfoot and his smash hit single “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” it’s a rare Michigander indeed who doesn’t know that Lake Superior “never gives up her dead when the gales of November come early.” The Fitz is the most recent lost freighter and undoubtedly the most famous, but it is far from the only large ship to be wrecked on the vast, powerful lake. As the Copper Country braces for the arrival of this year’s gales of November, let us take a look back at just a few of the other vessels that Superior has claimed.

The most adventurous of Great Lakes divers will recognize the name Kamloops. The steamship, a package freighter, was bound from Hamilton, Ontario, to the Thunder Bay region in late 1927. Among the cargo was special machinery imported for a Canadian papermaking company and a substantial amount of food, including rolls of Lifesavers candies. When the Kamloops entered Lake Superior from the Soo Locks on December 3, it paused to wait out a wintry squall. Unfortunately, this wise decision to avoid one storm placed the Kamloops directly in the path of another as it neared Isle Royale three days later. It seems that the ship either capsized under the burden of waves and ice or, blinded by the falling snow, sailed unknowingly onto the reefs surrounding the island. Searchers did not locate any sign of the Kamloops nor its crew of 22 men and women until the following spring, when the bodies of nine people were discovered on the nearby shore. They had donned lifebelts and fought their way to land in a lifeboat, only to perish while waiting for rescue. Fifty years after the sinking, in the late summer of 1977, divers finally found the hull of the Kamloops itself, lying on its side in two hundred feet of water just off Isle Royale.

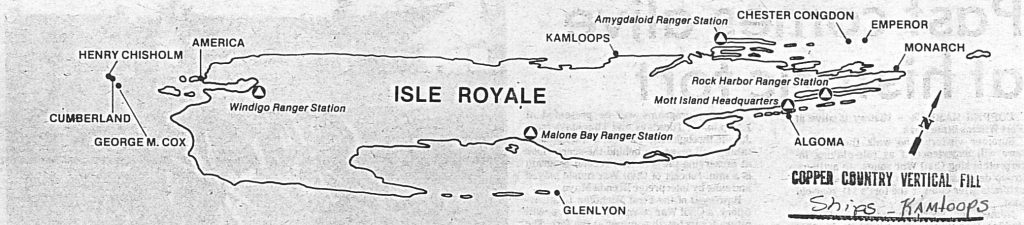

Map from a Daily Mining Gazette article showing the locations of notable shipwrecks near Isle Royale. The site of the Kamloops is noted in the north central part of the map.

Isle Royale was the site of another notable wreck a little over forty years before the Kamloops went down. The Algoma, launched in 1883, was a steamship operated by the Canadian Pacific Railway and described by one observer a century later as “modern and capable even by today’s standards.” The steamer had electric lights throughout, a remarkable feature in the 1880s, and its hull was equipped with watertight compartments advertised as a sure way to prevent sinking. If this sounds faintly like a certain 1912 shipwreck in the Atlantic Ocean, it should. What felled the Algoma was not an iceberg, however, but a natural feature on Lake Superior. On November 5, 1885, the ship departed Owen Sound, Ontario, in Lake Huron, en route to the north shore of Superior. Driving winds and freezing rain from one of the lake’s famous storms pummeled the Algoma as it neared Isle Royale. Miscalculating his ship’s proximity to the island due to low visibility and limited navigational aids, Captain John Moore unwittingly ordered the vessel be sailed over craggy rocks that obliterated its rudder and sent it into a vicious roll, scattering lifeboats uselessly into the lake. Vicious waves continued to break off pieces of the Algoma, which remained hung up on the rocks that had doomed it, throughout the night. Eventually, the eleven survivors managed to launch the last remaining lifeboat and a number of crude rafts, which carried them to relative safety on Isle Royale’s Rock Harbor. At least thirty-seven other souls aboard the ship were lost.

The SS Algoma was no stranger to rough seas on Lake Superior. The year before it sank, the ship was photographed arriving at its destination with a heavy coat of ice, courtesy of waves breaking over its railings.

The close of World War I brought one of the most unusual and mysterious Superior sinkings. In late 1916, the thick of the war, the French navy had ordered a large number of minesweeping vessels to clear their ports of explosives left by the Germans. The ships were to be built near Thunder Bay, Ontario, and sailed across the sea under French command after a formal commissioning. Two of these minesweepers, the Cerisoles and the Inkerman, were completed in September and October 1918, respectively. When sister ship Sevastopol was launched in late November–after the war had ended–the three began their journey toward France. The course their commanders plotted would take them past, yes, Isle Royale, around the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula, down along the south shore of the lake, and finally downbound through the other lakes. Unfortunately, the weather, always capricious on Lake Superior, had soured by the time the minesweepers passed Isle Royale and headed for the Keweenaw. According to an article written by amateur historian Richard Rupley, winds reached gale force, wet snow fell in sheets, and “waves mounted into dark mountains of crushing water,” forcing all hands into a battle with the elements. No one has ever determined precisely what happened that dark November night, but when the Sevastopol drew up along the leeward side of the Keweenaw, it did so alone.

Some delay in reporting the disappearance of the Cerisoles and Inkerman undoubtedly added to the mystery, but the lack of obvious debris or victims in the water made the investigation even more challenging. Weeks of searching uncovered only a few possible pieces of flotsam and sketchy reports of potential sightings or distress calls. Even investigations several decades after the sinking, conducted with the best of modern technology, could not locate the final resting place of the minesweepers nor of the seventy-eight men on board. Just in time for the centennial of the loss, however, a team of researchers is preparing to try again. Perhaps this time will be the charm.

The Navarin, a sister minesweeping ship to the Inkerman and Cerisoles. Both lost vessels would have been essentially identical in appearance to this one.

Will the gales of November come early this year, especially around Isle Royale? Some would say that we had our first taste in October, but the forecast for the time being seems to call for smoother sailing. Let us hope that this shipping season on the Great Lakes passes uneventfully, bringing everyone on the waters safely home.

I worked on Isle Royale as Capt. of the Tug J.E. Colombe for 7 years plus I have been diving the shipwrecks since 1960. I was the first to locate many of the wrecks and dive on them. All the Artifacts that I salvage from these wrecks I donated back to the NPS including the helm from the Algoma which is on display at Rock Harbor Lodge.

Capt. Metz! I certainly enjoyed reading all of your books! Good stuff! Real true stories of life on

the lakes!

I remember well that stormy night. The wind in Hancock were like I have never seen! As a native of out wonderful Upper Peninsula I have seen much in my 60 plus years. The storm where the people were swept off of the black rocks near Marquette was its equal I think. Thank you for all the wonderful writing and I anticipate more to come BRAVO!! Good job