A young soldier of the losing side sat astride his horse on the banks of the Rappahannock River in Virginia. His unit had surrendered to the Union Army, and the soldier, his cousin, and another comrade-at-arms once again traveled the familiar, well-worn roads of King George County. Now, as the three waited for the scow that would ferry them across the river, a dilapidated wagon “drawn by two very wretched-looking horses,” as the soldier later said, pulled into view. A stranger jumped down from the wagon and, upon learning that the three were Confederate veterans, explained his predicament. He and his brother had just escaped from a Union prison, and the brother had sustained a serious leg injury. The wounded man now sat uncomfortably in the wagon, whose driver refused to carry them any further. Could the soldiers help?

“I at once said we would help them,” the soldier recalled in his later years. Hearing his agreement but not the rest of the explanation, the injured fugitive clambered out of the wagon “and walking with evident pain, with the aid of a rude crutch, came towards us… as he came forward, he said, ‘I suppose you have been told who I am?’” They had, replied the young soldier, thinking that the man was referring to his brother’s tale of their prison escape. Instead, the wounded newcomer “said sternly, with the utmost coolness, ‘Yes, I am John Wilkes Booth, the slayer of Abraham Lincoln.’”

Major Mortimer Bainbridge Ruggles held firm to his offer of assistance. His chapter in the Lincoln assassination began on that riverbank.

But this story doesn’t start in King George County, Virginia, in April 1865. It begins in Copper Harbor, where Mortimer Ruggles spent his earliest days at a newly-built military outpost called Fort Wilkins, in the company of his parents, Daniel and Richardetta. His mother had a sister, who also resided at the fort for a time. Her name was Fanny Hooe.

After the Treaty of LaPointe, signed in 1842 and ratified in 1843, ceded the copper-rich Ojibwa territories of the western Upper Peninsula to the United States government, that same government felt certain that disputes would erupt between prospecting miners and those who objected to the cession of their aboriginal lands. To keep any conflicts at bay, the powers that be authorized the construction of a fort at the fledgling settlement of Copper Harbor and dispatched two infantry companies to garrison it in 1844. After a northward journey of more than two weeks–blessedly undertaken in May rather than in the heart of winter–the soldiers arrived at the harbor. Among them was Lieutenant Daniel Ruggles, a Massachusetts-born graduate of West Point with a decade of military service under his belt. Unlike many of his enlisted men, Ruggles enjoyed the pleasure of being accompanied by his family. Joining him in this new assignment were his young son, Edward, and his wife, Richardetta, who was far from home in more ways than one.

Richardetta Mason Hooe was born on November 19, 1821, according to her headstone; other sources place the year at 1820. A native of Virginia, her ties to the state ran deep. Through her mother, Elizabeth, “Etta” descended from George Mason, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention known for his strenuous objection to the powers given the federal government and the original document’s failure to outline rights intrinsic to citizens. The Bill of Rights eventually added to the Constitution found its roots in Mason’s own 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights. Mason’s influence on Virginia and on the fledgling nation was profound, and while Etta may not have literally lived in her late ancestor’s shadow, she bore his name and his pride in the state.

In addition to her close ties to a Founding Father, Etta found her life intimately bound up with the military. Her father, Alexander Seymour Hooe, served in the War of 1812; her brother George died in naval service in 1845. By enlisting in the Army, her eldest brother Thornton may have changed the course of Etta’s life. Elizabeth and Alexander Hooe had died by the time Richardetta was fourteen. As the oldest son in the family and a man accustomed to leadership, it would not have been surprising for Thornton to take responsibility for his younger siblings. Although the 1840 census recorded only the name of each head of household, the statistics tallying the other members of Thornton’s home offer some possibilities that Etta may have been among them. Residing with Captain Thornton Hooe, his wife, and their two children at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, that year were two young women who would have been the same ages as Etta and her nearest sister, Frances. If they were, life on a military fort on the American frontier would have been a far cry from their family mansion in Virginia–but a taste of what was to come.

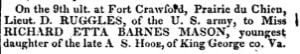

Sources offer no verifiable insight as to whether Etta met and was courted by Daniel Ruggles at Fort Crawford or at home in Virginia. When the two tied the knot, however, they did so at this remote outpost. The September 16, 1841, edition of the Army and Navy Chronicle reported under its marriages column: “On the 9th ult. [last month] at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, Lieut. D. RUGGLES of the U.S. army to Miss RICHARD ETTA BARNES MASON, youngest daughter of the late A.S. Hooe, of King George co. Va.” For better or for worse, young Miss Hooe had yoked her future to that of a career military man. His life and hers–and those of their eventual children–would be forever bound up together and their stories forever linked to the choices made two decades later.

But all that was still to come. The time of service at Fort Wilkins lay on the horizon first. The soldiers had arrived to a wilderness. Lake Superior, which had been their constant companion for the last leg of the journey, lay to one side; a more tranquil inland lake sat on the other. The fort would be built on the strip of land between them. As Mac Frimodig subsequently wrote, “With a fine stand of construction timber just across the lake and a great profusion of foundation rocks at arms’ length in every direction, there remained for the soldiers only the task of rearranging the two commodities to accommodate themselves.” By late July, the officers’ quarters, where the Ruggles family would reside, were ready for plastering and finishing. Thanks to the steady work of carpenters and soldiers, as well as shipment of windows, shingles, and other supplies from Detroit, the entire fort was prepared to meet the first fall of snow. Everyone had to be thankful for that, but Etta, one reasons, was the most grateful of all.

Already the mother of a one-year-old, she was pregnant again, and the baby was due in December. Many women seek the advice and company of their own mothers during pregnancy, but the late Elizabeth Mason Hooe could offer no comfort to her daughter. Perhaps to spare her sister some loneliness, Frances “Fannie” Hooe traveled north to Copper Harbor. Etta and Fannie saw the new fort buildings rise around them, saw the military community plant a vegetable garden on the east end of the unnamed inland lake. Sadly, the seed potatoes tended over the warm, dry summer yielded fewer to harvest than were planted. The two sisters probably walked along the shore of the lake and maybe down to Lake Superior, taking little Edward with them. Fannie, it seems, captured the imagination of the youthful soldiers who were far from their own sweethearts. An exhibit at Fort Wilkins Historic State Park today quotes a letter from George Saunders who expressed his appreciation for Fannie by sending “some agates… for Miss Hooe.” Of course, the greater honor came when the units christened the lake adjacent to Fort Wilkins after their charming visitor. Nearly two centuries after she left Copper Harbor and went home, the lake still bears Fannie’s name, albeit with the spelling Fanny Hooe.

Those who have not seen the Keweenaw Peninsula in the winter do not know the great hush that falls over the region with the first snow. It is as if the world itself holds its breath in awe and anticipation of what is to come; every sound is muted, every echo swallowed up by the silence. Into this quiet place came Mortimer Bainbridge Ruggles on December 11, 1844. His birth was a bright spot in an otherwise bleak winter. The previous month, provisions shipped to Copper Harbor had disappointed the garrison: only a fraction of the potatoes and pork were edible, if one used a liberal definition of “edible.” The hay supply for the oxen proved inadequate. Faced with the possibility that the draft animals might starve, Daniel Ruggles ordered eight of the draft animals butchered; at least in death, they could provide one last service to the population of Fort Wilkins. Meanwhile, the people–now plus one infant–waited anxiously through the hush of winter, anticipating a second growing season at a more promising garden site and liberation from the cold.

Political developments thousands of miles south changed the plans of the Ruggles family considerably. War with Mexico loomed, and the Keweenaw mining boom had proven far more tranquil than the government had feared. Military superiors dispatched the two companies at Fort Wilkins southward in 1845, sending replacements to garrison the fort. Daniel Ruggles headed to Texas and then to Mexico itself; he saw action in several battles that earned him a promotion first to Captain, then a brevet (honorary promotion) to Lieutenant Colonel the following year. He and Etta would spend the next decade making a round of the growing United States, including another stay in Texas, where their eldest had been born, and a sojourn in Utah. Mortimer stayed with his aunt for at least part of this time: the 1850 census records him in the Virginia household of Mortimer and Elizabeth (Hooe) Bainbridge, where he found a friend in his slightly younger cousin, Absalom. Finally, with Daniel’s health flagging, the Ruggles family settled down for a recuperative leave of absence near Etta’s Virginia home.

Then the Civil War came.

By virtue of his commission and his Massachusetts birth, Daniel’s loyalties belonged to the Union Army. Something else, however, prevailed in his mind and heart. One imagines the intense conversations that must have taken place between husband and wife in those turbulent days. Whether it was Etta’s deep Virginia roots, her family’s history as slaveholders, his own convictions about the war, or some other matter entirely that led him to the decision, Daniel made an irrevocable choice on May 7, 1861. He resigned from the United States Army and received an appointment in the Provisional Army of Virginia shortly thereafter. In August, he became a brigadier general and held that rank until the end of the war, seeing action at Shiloh and at various sites along the Mississippi River.

Daniel’s devotion to the Confederacy–and probably Etta’s as well–found a home in the hearts of their sons Edward and Mortimer, and so Mortimer Ruggles came to be on the banks of the Rappahannock with John Wilkes Booth that fateful night in April 1865. He, his cousin Absalom Bainbridge, and Willie Jett crossed the river–crossed the Rubicon, really–with Booth and his associate, David Herold, and traveled with them to the town of Port Royal. Together, they searched for a place to shelter the assassin and his conspirator, holding to the story that Booth was a wounded soldier. After they secured a room for Booth for the night, the others split up among friends’ homes and hotels. Mortimer and Absalom reunited Herold and Booth the next morning and headed on their way, only to run into Union troops at the river. Willie Jett was captured soon after. Some sources record that Mortimer Ruggles and his cousin rode back to try to warn Booth and Herold; when he wrote of the incident in an 1890 magazine, Ruggles made no mention of it, instead saying that he and Bainbridge fled homeward when they heard the news of Jett’s capture and, soon after, Booth’s death in a barn standoff. Ten days later, Mortimer said, “I was arrested at night by a squad of United States cavalry,” along with Absalom, and “taken to Washington and placed in the Old Capitol Prison.” Later, he was imprisoned on Johnson’s Island but released a few days later upon agreeing to take an oath of allegiance to the United States.

So the native of Copper Harbor returned to regular life, leaving his days as soldier and accessory behind him. In 1877, he married Mary Holmes in New York City, where he lived out the remainder of his days. Back in Virginia, Fort Wilkins veteran Daniel Ruggles worked as a real estate agent; Etta kept house, as she had in the Keweenaw, and stayed close to her family. Her sister, Fannie Hooe White, died in 1882. Daniel passed away in 1897 and Mortimer in 1902. Upon Etta’s death in 1904, she was buried alongside her husband in a Confederate cemetery in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Whatever choices the family made in the Civil War, they will always be a part of the Copper Harbor story.

Interested in reading more about Mortimer Ruggles’s aiding and abetting of John Wilkes Booth? Blog posts from Boothie Barn and Mysteries and Conundrums were some of the many sources that informed this post. The Internet Archive also makes available the firsthand account Ruggles published in the Century Illustrated magazine in 1890.

Holy Wah what a story!!! The names are familiar the story is not. These blog posts are something to look forward to with great anticipation. There is not an uninteresting one in the bunch. Keep Em coming writers.