Some ghost towns refuse to give up the ghost. Central Mine is one of them. Winona is another.

In September 1974, the Daily Mining Gazette wrote that “the motorist moving between Houghton and Ontonagon seldom turns to the right to see what is left of the community.” This has not changed in forty-five years: most passing down M-26 have appointments to keep or recreational plans that do not include visiting this modest hamlet, whose population, at the last semi-official update, was nineteen people. Yet Winona has received its share of attention in recent years, far more than most copper mining towns that have depopulated since the decline of copper mining. In December 2019, its tiny school landed in the pages of the Detroit Free Press as part of that publication’s Tales from the Rural North series. A few years earlier, Michigan filmmaker Michael Loukinen spotlighted Winona in one of his documentaries. The film even enjoyed a premiere at the Copper Country’s most elegant venue, the Calumet Theatre.

What can be said about this place?

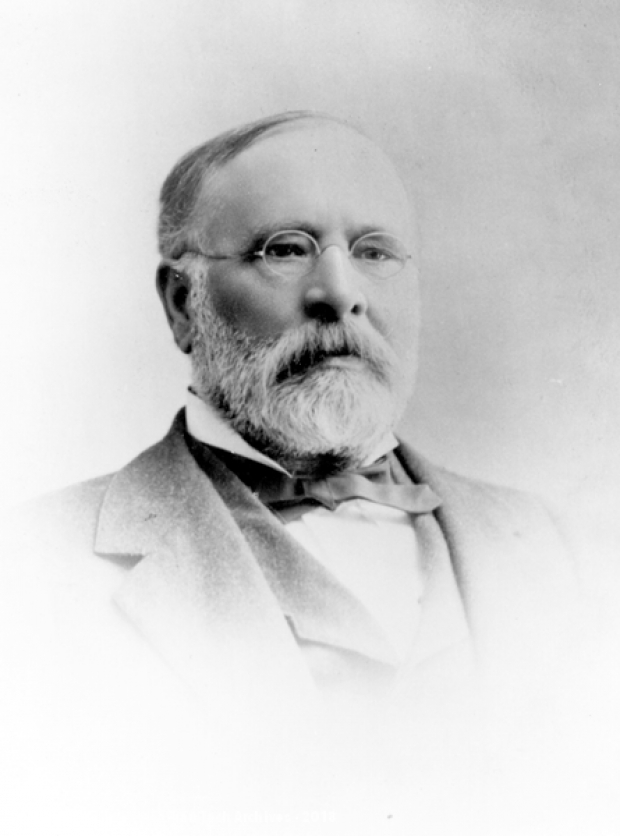

Winona had its roots in the prehistoric copper mining of the local native peoples. Evidence of their pit workings attracted the attention of prospectors and investors as the Keweenaw Peninsula began to industrialize, and the Winona Mining Company was organized in April 1864. Later that year, proprietor Jay A. Hubbell wrote in a prospectus that they had already made significant strides toward making the new mine a going concern, including “the opening of promising cupriferous [copper-bearing] deposits, the erection of several dwellings and other buildings, and the acquisition of a further general knowledge of the value of the whole territory.” A vein of amygdaloid trap rock most captured their attention, and they noted the presence of ancient pits along the way. From that vein, the prospectus noted, workers had already detected ample copper and even some “fine specimens of native silver.” Hubbell argued that the Winona had already proven its worth: “of the value of these indications the most skeptical must be satisfied… the value of its mineral deposits having been fully and satisfactorily proven.” Those interested in purchasing stock were most welcome to do so, and they could have “a full confidence in its immediate and prospective value as an investment.”

The mine went nowhere.

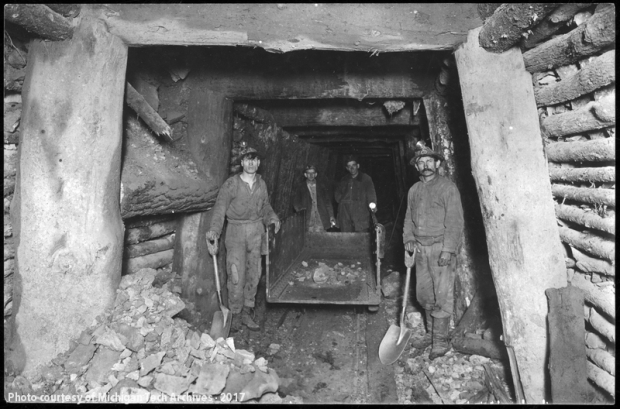

At least, it went nowhere at first. Those 1860s efforts petered out as rapidly as they had begun, being worked only sporadically over the following decades. Mining along the range south of Houghton, however, experienced something of a renaissance in the 1890s. Winona would share in this good fortune. In 1898, the mine reorganized under a new name, Winona Copper Company, and began diamond drilling explorations at the western end of the property. These investigations over the first few years provided reason for cautious optimism, and the company built a new store, meat market, and icehouse. By March 1902, although the directors thought it premature to construct a stamp mill at Winona, they discussed seriously the possibility of leasing unused stamps from the Atlantic mill and ultimately did so in December. Miners and other laborers began to descend on Winona to stope out various levels of the promising shafts, and the company authorized the construction of two duplexes for families in 1903.

As the decade wore on, the management–connected as they were to the successful Copper Range Company–decided to step up their efforts at Winona and attempt regular production. In 1906, they constructed a track to link up with the Copper Range Railroad track a little to the east. “A new modern steel shaft and rock house” was built at the No. 3 shaft; the annual report described it glowingly as “at least equal to any in the Lake Superior region so far as convenience and economy of operation are concerned.” Most notably, the Winona Copper Company acquired land from its neighbor, the King Philip Copper Company, which had been formed around the same time as the first Winona; the new property arrangement allowed “each Company… [to] mine out more economically its ground” between the No. 1 at King Philip and the new No. 4 that Winona sank that year.

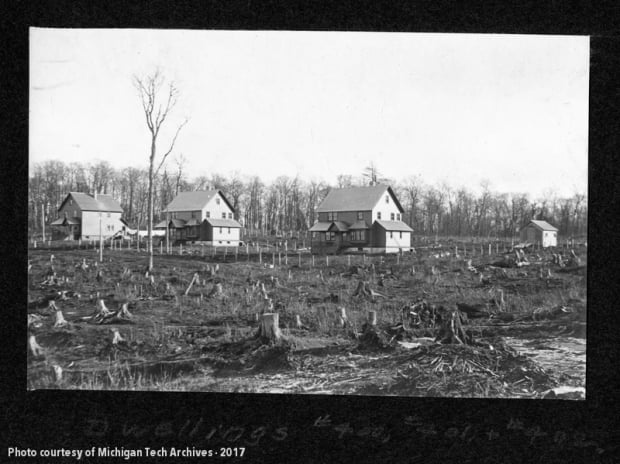

Most importantly for the town that would become Winona, the company planned to build “twenty or thirty new dwelling houses for miners” in 1907. It did, describing the structures as “twenty six-room single houses, each 20 feet by 26 feet with… pantry and vestibule” and “two seven-room single houses, each 24 feet by 30 feet,” with similar pantry at the rear. It continued to construct these kinds of dwellings for its employees over the following years, as well as larger homes for the mine captain, physician, and stamp mill superintendent. Winona was finally building its own stamp mill. The town was growing, too, with a new large schoolhouse rising near the heart of the settlement. Unlike the old log building where children had received their education previously, the two-story school would house twelve grades. In the 1930s, a WPA project added an auxiliary building with a gym floor to accommodate the school’s successful basketball team. Winona residents were sportly folk and also enjoyed America’s pastime, fielding a summer baseball team.

As long as the company was expanding, it decided to go one step further and merge with the King Philip. In March 1911, the new stamp mill processed its first shipment of rock; later that year, the Winona Copper Company acquired all of the King Philip’s stock and began hiring new employees to increase their output. “Good men have been coming slowly,” the annual report for that year opined, and 1912 saw an almost critical shortage of trammers, but the future seemed bright.

Unfortunately, predicting the days ahead for a copper mine is never an easy task. The following July, the Western Federation of Miners strike began. “From all information attainable,” wrote mine superintendent Rex R. Seeber, “it appears that very few of our men joined the federation until after the strike was called. Order was preserved on the location and no arrests were necessary on account of the strike.” Union fervor seems truly to have been less–or need for money–greater in Winona than in some other parts of the Copper Country: a full shift of men returned to work at the Winona Mine by October. The mine weathered the strike and hustled through the heightened demand for copper induced by World War I. When the market crashed after peace, however, Winona’s hope of profit went with it. Directors decided to suspend operations temporarily at the end of January 1919; the hiatus persisted until August, but the reopening brought little hope. The mine needed to be expanded, but “the working force is depleted,” and a few explorations around one of the closed King Philip shafts led to nothing. There was some possibility of the mill, judged to be one of the finest of its type in the region, continuing to operate, but this, too, proved fruitless. The mine shut down for good in May 1920.

The 1916-1917 Polk Directory for Houghton County listed the population of Winona at 1,200. It had a Finnish temperance society–reflecting the background of many of its residents–a park association, and a social club. When the mine closed, the town began to disappear. Some turned to moonshining to stay afloat. The Pampa Company, a lumber business, tried to fill the place of copper mining by opening a mill in Winona in 1921. It burned the next year, was rebuilt, and closed when the Depression came on. Other sawmills and logging companies, including the Riippa Brothers from the 1940s on, later employed some of the people who remained in Winona. For the most part, however, the residents began to leave to seek work elsewhere. As the mine goes, so does the town. In the 1950s and 1960s, Winona consisted of a few dozen residents. High schoolers now had to ride the bus to Painesdale rather than walk up the gravel road for classes. But the elementary school stayed, even as Winona lost its barbershop, its post office, and now all but a handful of its people. Like the ruins of the stamp mill or the little Lutheran church on the highway, it testifies to a time and a place that have faded into memory.

Awwwww shucks gives me chills!! I played in the ruins of the mines and stamp as a kid. It is a nice story that I am glad has been told. Thanks MTU