The more things change, the more they remain the same. Much about life–the way Americans dress, the types of jobs available to them, their methods of travel, the ways they communicate–has changed since 1900, and yet so much remains the same. People have a fundamental desire to visit with old friends, meet new ones, let down their hair, and enjoy themselves. The Copper Country is no different, and, in its heyday, the opportunities for entertainment grew as numerous as the mines. In a prior Flashback Friday, this blog profiled the bands formed by mining companies and communities. Now the focus turns to a venue where these bands often played for eager listeners and excited dancers at the turn of the last century.

Nestled in the woods between the bustling copper metropolises of Hancock and Calumet sat Electric Park, a project of the Houghton County Street Railway Company (later the Houghton County Traction Company). In the early 20th century, rail lines crisscrossed the western Upper Peninsula, carrying new arrivals into the region and bearing products like copper ingots and timber to points beyond. The street railway’s electric cars filled a niche for local passenger traffic and established what railroad historians Wally Weart and Kevin Musser characterized as “the only true interurban line in the Upper Peninsula.” When the streetcar line opened in 1900, travelers could go only between Houghton and Boston Location; within a year, the route expanded to Calumet and subsequently added a branch line to Hubbell. A final expansion, completed in 1908, carried riders as far north as Mohawk, with stops all along the way.

Passengers normally rode interurban lines to journey from community to community, but businesses like the streetcar company saw a profitable opportunity in creating another reason to ride their trains. What if they could be the exclusive transportation to an attractive leisure destination, the sort of place where friends wanted to gather and have fun? As spring arrived in 1902, the company moved quickly to capitalize. It obtained access to a patch of land, a little north of Boston Location, dubbed “the Highlands” and hired a contractor to begin clearing brush from the property. The Copper Country Evening News described the plans for the park:

“The pavilion will be a structure of 100 feet by 50 feet and will seat in the neighborhood of 300. When the floor is cleared dancing will be indulged in by several hundred couple [sic]. Amusement each evening and on Sundays will be furnished and refreshments being served on the grounds, people will be able to stay and enjoy themselves several hours at a time.

The entertainments given will be of the best and will be free of charge, all that the railway company will make off the investment will be the revenue derived from the fares to and from the Highlands. The fares promise to be quite an item and the resort or park will prove to be a very popular place for certain classes in this section.”

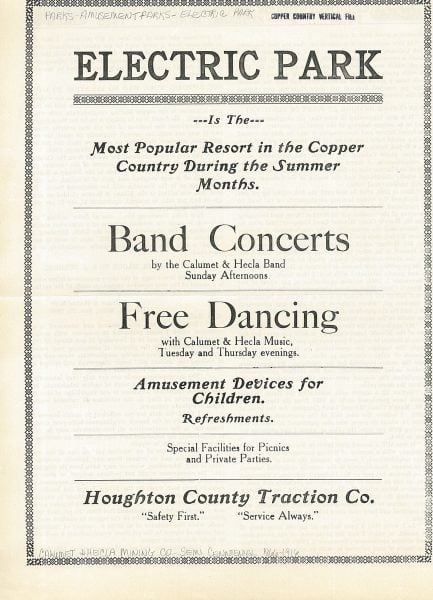

This strategy worked. Enjoying high-quality entertainment with friends and basking in the delight of a Copper Country summer for no more than the cost of a streetcar fare drew scores of residents to the park. In 1910, the Houghton County Traction Company recorded some 50,000 visits to the little grove during the warm weather season. By this time, the park had long since shed the Highlands moniker. After a few years of being called Anwebida–a name purported to mean “here may we rest” in Ojibwe–it became Electric Park, a title that required no explanation to those who didn’t speak the language. And the atmosphere there was as electric as the name.

Electric Park kept bustling throughout the summer seasons. The 50,000 visits in 1910, as in most years, covered a whole host of events, gatherings, and activities. Bands descended on the park from the start, with both the Calumet & Hecla and Quincy corporate ensembles playing afternoon concerts. A typical C&H program covered a vast artistic field, incorporating Verdi, patriotic marches, ragtime, and other genres so as to appeal to all tastes; if hired for a dance, the musicians served up an evening of waltzes and two-steps, the toe-tapping favorites of the time. Dances proved particularly popular at Electric Park and in some years were held three times a week. The original dance pavilion burned to the ground in 1906, but its popularity prompted an almost immediate reconstruction and an expansion by nearly 25 percent.

This new pavilion was well-suited not only to the fashionable dances held at Electric Park but also to the other entertainments and groups that descended on the grove. A stage and dressing rooms, balconies framing the dance floor, large open-air porches, and game tables provided crowd-pleasing, well-equipped spaces. Fraternal organizations rented the Electric Park pavilion to host their own festivities. The UP Federated Italian Societies, for example, hosted a reunion and picnic there with a “program of speeches and sports,” a band concert, and a boccia ball tournament, promising “a day of fun and entertainment for everybody.” The Laurium chapter of the Knights of Pythias held dances at Electric Park; the Hancock and Calumet councils of the Knights of Columbus did the same. Elementary students celebrated the end of the year with a big to-do at the park. Nearby Lutheran and Methodist Sunday Schools took their students out to the grove for picnics and showcases of what they had learned. The Methodists in particular made a habit of bringing large events out to Electric Park, hosting an annual “chautauqua” (convention) of presentations, missionary visits, and music for members of the denomination there throughout the 1910s.

Whether they came to attend a Sunday School picnic, a company band concert, or a fraternal organization party, Electric Park kept its visitors happy. Children zipped down wooden slides and played merrily on unique “boat swings” that sometimes attracted adults, too; management had to post a sign on each reminding older visitors that “this swing is for children only.” Men and kids alike played baseball on a diamond surrounded by a thick stand of trees. As the sun faded, a massive “ELECTRIC PARK” sign, said to be the largest electric sign in the region, blinked on and cast a romantic aura on the grove. When guests of the park needed something to eat or drink, they could purchase snacks like popcorn and sarsaparilla–or visit the outdoor water pump for free refreshment. In the earliest days of the park, supposedly, those looking for adult beverages could find their poison also close at hand. Quickly, however, Electric Park abandoned any liquor sales and forbade patrons from bringing their own, hoping to preserve a true family atmosphere not available at most Copper Country entertainment venues.

Although Electric Park tallied tens of thousands of annual visits for many years after its inception, as first the Copper Country entered an economic decline and then the Great Depression arrived, its days were numbered. As a cascade of mines entered hibernation and people moved away to seek jobs in Detroit, Milwaukee, or Chicago, fewer and fewer passengers rode the Houghton County Traction Company’s streetcars. The company folded. All operations ceased on May 21, 1932. Orphaned by the collapse of its parent organization, Electric Park struggled on for a time. Concerts and dances became much more sporadic, although organizations still put on the occasional picnic, but the summers when the park dominated local entertainment became mere memories. World War II and the cost of maintenance proved the last straws. Electric Park’s pavilion was soon scrapped, sold, and reassembled as a potato barn. Only traces remain of its once-bustling streetcar station, picnic grounds, and dance hall, buried in the underbrush like so much Copper Country history.

Electricity coursed through my power lines (veins) while reading this blog!I am not nearly old enough to have tasted the food and fun,but a vivid imagination stirred by this blog makes me almost hear the merriment and taste the food.

Thank You for this