There is a newly formed Michigan Tech chapter of the Climate Reality Campus Corps, a national movement of University campuses associated with the Climate Reality Project. The student leaders of the Michigan Tech chapter recently hosted a 24 Hours of Reality event explaining the science, impacts, and solutions of the climate crisis while also highlighting how Michigan Tech fits into the bigger picture. The video of that presentation is now available for anyone to watch here. The Michigan Tech Climate Reality Campus Corps is asking Michigan Tech to start planning for a transition to 100% renewable energy for campus electricity. Michigan Tech can demonstrate its leadership in sustainability and resilience through this commitment, and student leaders on campus are ready to have conversations about making this campaign a reality!

Are you interested in how Michigan Tech gets, uses and saves energy? If so, stop by the Sustainability Stewards meeting on Wednesday, October 21st at 8pm to see information from the Energy Pie-Chart, the 50% commitment to wind, alternative energy on campus, and easy ways you can reduce your energy footprint today.

Guest speakers include: Larry Hermanson from Facilities Management, Jay Meldrum from the Keweenaw Research Center, Rose Turner from the Sustainability Demonstration House, and Kendra Lachcik from the Campus Corps.

You can join the meeting via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/9499596761

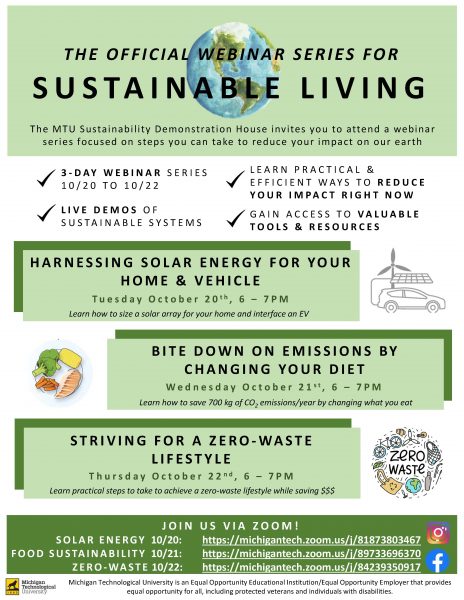

Since the MTU Sustainability Demonstration House (SDH) is limited in opening the house and its activities to the public this semester, SDH is bringing the house and all of its sustainable systems to virtual viewers!

You are invited to join MTU SDH for a series of webinars centered around various aspects of sustainable living:

Tuesday, October 20th: Harnessing Solar Energy for Your Home & Vehicle Learn how to size a solar array for your home!

Join via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/81873803467

Wednesday, October 21st: Bite Down on Emissions by Changing Your Diet Learn how to save 700 kg of CO2 emissions per year by changing what you eat!

Join via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/89733696370

Thursday, October 22nd: Striving for a Zero-Waste Lifestyle Learn practical steps to take to achieve a zero-waste lifestyle while saving $$$!

Join via Zoom! https://michigantech.zoom.us/j/84239350917

You won’t want to miss out on these talks!

- View live demos of the MTU SDH sustainable systems

- Gain access to valuable tools & resources

- Learn practical and efficient ways to reduce your impact right now

Please email sdh@mtu.edu with any questions or concerns. We hope to see you there!

The Working Group of the Tech Forward Initiative for Sustainability & Resilience (ISR WG) recognizes the work of the Keweenaw Youth for Climate Action (KYCA) in developing the Petition to ask Michigan Technological University to divest all funds from the fossil fuel industry. The efforts of the KYCA are aligned with the goals of Michigan Tech to demonstrate leadership in sustainability.

The ISR WG endorses the effort and supports this call for Michigan Tech to begin the fossil fuel divestment process and improve transparency and participatory decision making regarding institutional investments.

Some of the main points in the petition include the need for transparency regarding current investments, halting and then divesting from any investments in fossil fuels, and building transparency and partnership into the structure of future investments, giving students a voice in the University’s investment process. While transparency regarding investments and participatory models of investment decision making may not seem immediately connected to fossil fuel divestment, these metrics are included in the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education STAR’s system for evaluating achievements in sustainability at Universities, as sustainability includes dimensions of social engagement, participation, inclusion, and justice.

The ISR WG recommends that Michigan Tech adopt the recommendations called for in the KYCA petition and that all future university investments are evaluated for environmental impact, social justice, and sustainable business practices. Michigan Tech must lead by example, and the future needs Michigan Tech because the future needs innovative transformation in sustainability practices that decarbonize our society, enhance social justice and inclusion, and regenerate the collective capacity to contribute to resilient ecosystems and quality human lives.

Keweenaw Youth for Climate Action is leading the way by crafting and circulating a petition asking Michigan Tech to divest from fossil fuel investments. The petition can be viewed and signed here.

Some of the main points in the petition include the need for transparency regarding current investments, halting and then divesting from any investments in fossil fuels, and building transparency and partnership into the structure of future investments, giving students a voice in the University’s investment process. While transparency regarding investments and participatory models of investment decision making may not seem immediately connected to fossil fuel divestment, these metrics included in the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education STAR’s system for evaluating achievements in sustainability at Universities, as sustainability includes dimensions of social engagement, participation, inclusion, and justice. Michigan Tech is home to an Applied Portfolio Management Program within the College of Business as well as an degree program in Sustainability, Science, and Society and multiple Enterprise groups related to sustainability – these are all examples of students on campus who could benefit directly from learning about investment management processes that are socially, ecologically, and economically sustainable for the long term health of the planet (and the long term success of institutions of higher education).

This petition is just one recent example of student leadership at Michigan Tech in the domain of sustainability. Students across campus are interested in using their educational experiences to make real world change, within the institution and across our local community and beyond. Thank you for your leadership, Keweenaw Youth for Climate Action and students across campus who are championing sustainability through direct action and engagement!

Michigan Tech is highlighted in a recent article on studyinternational.com news on universities that drive sustainability forward. Specifically, the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering is highlighted as a sustainable choice for students “ready to become a responsible engineer.”

It is wonderful to see Michigan Tech highlighted for its strong programs in Civil & Environmental Engineering that teach sustainability and engage students as future leaders in sustainability in engineering. Michigan Tech also offers an undergraduate degree in Sustainability Science & Society and has multiple opportunities for research and campus engagement associated with sustainability.

The future needs Michigan Tech because the future requires we find ways to enhance sustainability and resilience, locally and around the world. If you’re looking for ways to contribute to a better future through your education and career, Michigan Tech provides opportunities for learning, leadership, and making a difference in everyday lives through your studies and your future profession.

This is a guest blog post from Zofia Freiberg, who can be reached at zjfreibe@mtu.edu.

Over 200,000 people were killed and 83% of them were Mayan. Some called it a civil war, and some called it genocide. A United Nations backed report concluded that of all the human rights violations, 93% were carried out by state forces and military groups. With the war having only ended in 1996 and the continual political turmoil, three-fourths of the rural population lives in conditions of abject poverty.

In San Juan Comalapa, a mural spanning 182 meters depicts the town’s history. Teachers, artists, students, and other residents of Comalapa painted the history of their culture, not to reinvent a sense of belonging in their nation, but to reclaim their past. Much of the mural features the violence of war, cultural suppression, and building collapse from earthquakes. Contrastingly, the final panels illustrate children attending school, carrying books, and embracing their Mayan culture.

Matt Paneitz was stationed in Comalapa during his Peace Corps service. He decided that he wanted to be part of the positive force making the final few panels of the mural a reality. He founded a non-profit organization called Long Way Home.

Long Way Home both physically and conceptually built a school system called Centro Educativo Técnico Chixot. The curriculum focuses on student-driven, community-based projects that address genuine needs. What is called “Hero School” is a place of democratic education built upon the idea that self-determination and democracy are fundamentally linked. Ultimately, the goal of the school is to empower students to build their own democratic systems and arm students with critical thinking skills to better handle symptoms of poverty. Education facilitated by cultures of privilege and power often become an indirect form of colonization. LWH actively works to avoid this; the curriculum is developed and facilitated by community members and taught in the native Mayan language Kaqchikel.

Prior to establishing the school, Matt was struck by the amount of trash floating through Comalapa. Though people depend on the land to grow food as their primary source of income and subsistence, trash is routinely dumped in a ravine that floods and pollutes the surrounding watershed. This motivated Matt to use alternative building techniques that combine naturalistic building with waste mitigation efforts.

Over spring break, a group of Michigan Tech students, myself included, travelled to Guatemala to volunteer with LWH and learn about their community impact and the Green Building Techniques used to build their campus. Equipped with sledge hammers and shovels, we learned how tires that were previously headed to the dump can be packed with sand and trash to create retaining walls or a structure for a home. Plastic sacks are placed on the bottom of the tires to hold in the sand that is packed down. Miscellaneous pieces of trash are also placed inside the tire.

As we unlaced our shoes and grabbed buckets of material, we learned how to make cob: 3 buckets of clay earth, 2 buckets of sand, 2 buckets of water, straw, and a funny foot feeling later we made our first batch of cob. There were many more to come, since cob is a staple material on-site due to the similar properties it shares with traditional concrete. It is used on-site to fill in space around tires for interior and exterior finishes as well as to build walls between concrete structures.The volunteers on the campus tuck their single-use packaging into plastic bottles to create eco-bricks. These-eco bricks are used as fillers in cob walls. Liter sized plastic bottles are cut into shingles for roofs to protect structures from both rain and sun. Using trash as building materials is especially effective because it minimizes what has to be brought to the site and elongates the useful lifecycle of items already on site.

In addition to the school for the local community, Long Way Home runs a Green Building Academy where participants come to learn about sustainable building methods while simultaneously contributing to current projects on the campus. The profits from the academy go towards funding the school. LWH demonstrates a model of service where contributions towards community development goals are not a zero-sum game where what is given up by one actor is gained by another. Instead, the transfer of value from one to another is a reciprocal exchange.

This was certainly true for the experience of the MTU students. Sitting in the airport waiting to depart, we discussed our expectations for the week. The consensus was that we had no clue what to expect. Yet in true Husky style, we were eager to put in hard work and help another community. Sitting in the airport waiting to return, the conversation had flipped from what we thought we would be giving to all the value we had received.

Bottom Row: Advisor Rochelle Spencer, LWH Volunteer Coordinator Abby, and Student Sara Schrader

What I found to be most valuable from the trip was a newfound understanding of what makes for effective volunteerism and foreign aid. Ultimately, I don’t think we directly helped another community so much as we became a part of the LWH community and their collective efforts towards positive change. Offering up what you have to give as an empathetic outsider may be generous, but it is more efficacious in the long term to first become a member of the community you intend to help. Then, you no longer have to guess at what a community’s needs are because your needs and that of the community become one in the same.

On the final panels of the mural in town, once just a vision, there is an illustration of the existing LWH school. Though LWH has a Hero School, they do not try to be the heroes of Comalapa. Instead of attempting to uproot and recreate existing social and economic systems, they build upon what already exists and give locals an avenue to become the heroes of their own community.

Attempts to decipher the best mechanism to make humanity better can be dizzying to the extent of paralysis. To make matters worse, incremental progression is easily diminished with a glance to the news. When the news becomes an omnipresent noise, it can be comforting to just accept that people around the world live differently. However, cultural acceptance shouldn’t be used as a justification for global inequalities. It is a heroic act in itself to acknowledge what incremental good you can do in the face of all the bad. Let a focus on what it is you do have to contribute strengthen your will to act.

This is a guest blog post from Nathan Hatcher, who is a Sustainability Science & Society Major at Michigan Tech. He can be reached at nrhatche@mtu.edu

Sustainability includes social, economic, and environmental aspects. Over this past spring semester, I became more aware of the sustainability activities that were going on behind the scenes at Michigan Tech. I learned about and attended events, like an Open House of the Sustainable Demonstration House and the planned (but put on hold because of the current pandemic) Waste Reduction Drive. Others dealt with more logistics, like universal recycling containers across campus.

The question of ‘How can we improve?’ became an interesting challenge. Improvements are essentially never ending, and can be implemented at various levels in the system, from individual student behavior, to the university leading the local community.

Below are some suggestions that Michigan Tech may be interested in looking into, followed by tips designed for the individual. Whether you’re a fellow student at Michigan Tech, part of the Houghton/Hancock community, or stumbled upon this online, these tips may help you think about how you can live more sustainably or how your workplace or school can become more oriented to sustainability in its practices.

Suggestions for Michigan Tech: In your search for how to become a better representative of sustainability, please consider some of the following ideas or their concepts.

- Website adjustments

- The university website platform could provide a place for students to be easily aware of recycling locations both on and off campus, which can help with reducing recyclable or reusable material in the landfill.

- The tips mentioned for individuals may also be of help. The list is meant to be expandable.

- Campus accessible gardens over winter (Indoor gardens).

- This may provide a way to enhance the social aspect of sustainability. Community, working together, building trust and relationships with others, helps improve sustainable practices.

- It can provide an active exercise for consideration of how others. A valuable tool, when determining the impact of an action/project on other people.

- It can also help address the Food Insecurity concern on campus.

- Course(s) regarding cooking and gardening.

- This provides a hands on way to understanding sustainability. From how crops are grown, to how food is prepared, and what can be done with leftovers. Composting, and organic growing methods can help with better understanding of the land and soil, and what might help improve it for continual use (taking fertilizers and related chemicals like pesticides out of the equation).

- Trading practice could help with the face-to-face interaction, knowing where food comes from or how it is handled. It also helps support the local economy in cases such as farmer markets. Farmers may be inclined to produce what gets more support, including how the food is grown (fertilizer or none, labor, permaculture, etc.) Students understanding the value of supporting others and how to support actions of interest may improve the quality of decision making.

Tips for the individual:

It does not matter who you are or where you are from, these tips are meant for everyone. Feel free to copy this list and expand on it if you would like. These tips may vary in value depending on your own situation, or lack-there-of. The goal is to become more aware, or mindful, of daily actions and what might improve them.

Rethink, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

- Rethink: Asking yourself some of these following questions may help you become more aware of what you are spending, and if it is really necessary at the time.

- Do I need it? (Is it a necessity or a want?)

- How much do I already have?

- Will it spoil before I use it? (Applies to anything with a date)

- What do I need it for?

- Do I need it for daily tasks? (Cooking, Cleaning, Hygiene, Work, Relaxation)

- What will I do with it later this week?

- How much do I need?

- Will I run out before my next shopping trip?

- Do I need it? (Is it a necessity or a want?)

- Reduce

- Only get what is needed

- What kind of waste will I generate by purchasing this? (plastic that cannot be recycled, non-reusable or non-recyclable packaging)

- Buy in bulk when it makes sense and is possible. (Does not expire for a long time, or, a lot is used in a short period of time.)

- Reuse

- What did I purchase or have that I can repurpose? (Large glass jars, tin containers, boxes, etc.)

- Glass jars can usually be washed in a dishwasher and be used in various ways. Like a coin bank, a detergent container, juice, salsa, screws, nails, magnets, etc.

- Boxes are helpful for moving, packing, and organizing. They can fold flat too without compromising the structure of the box. Do you know someone who needs some boxes? By offering boxes to them, you reduce what would have been waste, and they get a few boxes they may need.

- Some packaging material may be worth holding on to, if it is intact, and you know someone who could use some packing material, ask if they would like it.

- Recycle

- Check what all can be recycled in your local area and how to prepare the material, if applicable.

- Cardboard (there are a couple different types of cardboard)

- Various plastics

- Glass (usually jars or bottles)

- Paper (usually printer paper and magazines. Shredding it before recycling may be an option)

- Bags (paper ones are usually ok, plastic ones usually need to be dropped of at a retail store)

The overall goal is to provide ways of reducing how quickly your trash bin fills up, and therefore, reduce what goes to the landfill. This is not a set list of instructions; rather, they are tips meant to spark awareness or maybe some ideas as to how each one of us can play a part in living more sustainably. It may even save you some money!

The Tech Forward Initiative on Sustainability and Resilience recently held a campus-wide listening session to hear from more voices across campus. The event was focused on small-group discussions about what Michigan Tech does well, and what can be done differently when it comes to research, education, and campus life issues related to sustainability. Roughly 70 people showed up for a two-hour event on a weeknight, which is a really great indication of just how many people feel strongly about this topic! The folks working within the Tech Forward group are still accepting feedback, so if you did not get a chance to attend the event, please go to this Google Form and share your thoughts about how research, education, or campus life could be improved in regards to sustainability issues – or, feel free to tell us what we are doing that is already going well!

In Fall 2018, undergraduate and graduate students of Dr. Angie Carter’s Communities and Research class at Michigan Tech University (MTU) researched and wrote a report on the food system in the Western UP and food systems councils. The report, entitled “Cultivating Community Food Resilience” was the product of a partnership between MTU and the Western Upper Peninsula Planning and Development Region, and was intended to inform the development of the Western Upper Peninsula Food Systems Council (WUPFSC) through research and community engagement. It is hard to believe that more than a year has passed since we finished drafting the report, and that more than a year’s worth of WUPFSC meetings in all 6 counties of the Western Upper Peninsula region have since taken place.

We were both students in the class and came back together to reflect on the past year, the research and writing process, and sharing the report.

Question: Describe your process of preparing the report. What was the most impactful for you personally, for the class, for the community?

Kyla: I found the process of researching for this report immensely impactful, specifically connecting with community partners. The amount of support and enthusiasm we found when we started speaking to people about this project was really contagious and I think many of us found the sense of community very affecting. Especially after having graduated and left Houghton, this aspect of the project still impresses me.

I recall experiencing a lot of growth as a member of the class, too. The gains were far more than just intellectual — I think I have become a better community member through the process of pulling together to make this report happen. Coming into conversation with the community was the easy part of this project. The difficult part, the part that required all of us to stretch beyond our comfort zones, was the collaborative, messy work of birthing the report. I’m sure there will be many more experiences like this for folks continuing this work!

For the campus — I’m sure I’ll touch on this more when I talk about presenting to the Food Systems and Sustainability (FS&S) class. All of the MTU students I’ve met and talked to about this project and other community food systems topics have had such thoughtful, hopeful responses. I think that this report can serve as a little bit of a touchstone, a synthesis of much of the work that the first round of FS&S and Communities and Research students have done. Every time I look at the report, I am struck by all the elements that made their way in — from the literature we were exposed to during the first round of FS&S, to the problems, ideas, solutions and values that our partners and community brought to the table. So future students will find a lot of information and ideas, and they’ll have a snapshot of food resilience/security at MTU at a time before any of this work, or their work, was carried out. And they’ll hopefully see themselves in the vision of the students who came before them.

Courtney: The research for this project was interesting and impactful to me in a variety of ways. Not only educationally, but as a community member as well. It was really nice to interact with the students on campus and community members as a whole. I know that personally, all the people I came in contact with during this project were enthusiastic about the project and interested in what we were doing. It was in a sense, a feel-good process.

As a student, I grew immensely during this project; both as an individual and as a team member. We learned how each other worked, what our strengths and weaknesses were and where to improve. Presenting at the Social Science Brown Bag Lunch and the Western UP Food Systems Council Meeting at Zeba Hall in L’Anse, MI in December 2018 helped with my presentation skills which is huge both educationally and professionally. Attending the Western UP Food Systems Council meetings has given me the opportunity to connect with community members through the area, and learn about who they are through networking, sharing and brainstorming.

I believe this project helped our campus and community in a very unique way. Everyone loves food. Having conversations about food, how it is grown, the problems we encounter and how we can solve those problems. For the people who participated, they were able to express how food affects their life, whether positive or not. When starting this project, I was amazed at the number of people who are food insecure in our local area. No one should be without good food. It is my hope that doing the research and helping start the Western UP Food Systems Council, that we might be able to conquer some of the problems in our area.

Question: You’ve shared the report in a couple different forums, including WUPFSC meetings, classes and an academic conference. How can this report be used differently by different audiences?

Photo 1 Kyla Valenti presenting at the International Symposium of Society & Natural Resources conference

Photo 2 (L to R) Class team Jack Wilson, Kyla Valenti, Adewale Adesanya, Courtney Archambeau, Kyle Parker-McGlynn, Angie Carter (not pictured Rob Skalitsky) after presenting at the WUPFSC meeting December 2018

Kyla: Yes, come to think of it, those presentations all differed quite a lot. During the final week of the semester in the Fall of 2018, we shared our newly minted findings and research process at the second Western Upper Peninsula Food Systems Council meeting. During the spring, a couple of us came to Dr. Carter’s Food Systems and Sustainability class to talk about the project, findings and methods and to exchange thoughts and inspiration with other students concerned and passionate about community food systems. More recently, this work was presented at the International Symposium of Society and Natural Resources (ISSNR) in June, 2019.

After having either seen or participated in all of these presentations, I can confidently say that there are many different ways this report can be used and shared. It seems like each presentation, meeting and conversation has led in different directions and evolved the project further. For academic audiences, the conversation may have more to do with research methodology or may focus more on the theory informing this work — more generalizable information that could be applied to a wide array of projects in any number of communities and places. But with members of our own community, the conversation tends to be very different — it easily verges more toward concrete ideas and steps, acknowledges real people, local cultures, and tangible resources and connections. When we presented to other students, I recall experiencing a moment where I realized I’d need to shift from one gear into the other — from the academic gear, into one that was much more specific and personal. The Michigan Tech students I’ve spoken to and worked with have a strong connection to place and deep concern for their community, their school, and their impact.

Courtney: Sharing our research has probably been the best part of the project, next to all of the interactions of course. Sharing what we have learned on different levels was thought provoking and inspiring. The research and methodologies have been shared with students, faculty, and community members; each having their own sets of questions. When sharing with Dr. Carter’s Food Systems and Sustainability Class, their main focus was how we conducted our research and what we thought of our findings.

I think that “Cultivating Community Food Resilience” can be used in a variety of ways and be helpful to different types of groups. As I stated earlier, we have presented our work in a multitude of ways to a multitude of groups, and Kyla stated that each presentation, conversation and read-through has lead to different conversations and impacts.

Question: What are some of the next steps for the WUPFSC?

Courtney: One of the main things that needs to keep happening is the WUPFSC meetings in each of the six counties across the Western UP region. Food summits and community programs would also be beneficial so that community members know what is happening and or how to process foods in a variety of ways.

Kyla: What were once “recommendations” are now actualities. Ideas that once belonged to the future are now accomplishments. An example of this is that when we met with community partners last year, one of the key things that folks kept bringing up was that creating partnerships within the community was critical to supporting a strong local food system. “Building partnerships” ended up becoming one of our key themes, so several recommendations for the WUPFSC were built around that. And I have to say, checking back in with the WUPFSC, I am so impressed by just how far they’ve taken those initial recommendations. When I looked at the website after several months, I was amazed by all the resources compiled for that particular purpose: building partnerships. A “networking” page. Lists of community gardens. Funding opportunities. A calendar of local events. This is one area where even from a distance I can tell that the WUPFSC has done a tremendous job. And like many of those who participated in our project, I am optimistic that many of the “next steps” will grow from those partnerships!

—-

Kyla Valenti is a 2019 graduate of the B.S. in Social Sciences (Law and Society) program at Michigan Technological University. Though deeply attached to the UP, she currently resides in Silicon Valley, where she is working to advance her career as a social scientist and mental health practitioner.

Courtney Archambeau is a 2006 graduate of the B.S in Social Sciences (History concentration) program at Michigan Technological University. She is currently a full time employee of Residence Education and Housing Services at Michigan Technological University while pursuing her masters degree in Environmental and Energy Policy.

The students’ report, and other resources about food in our communities, can be found at the Western Upper Peninsula Food Systems Council website.