Joshua Pearce shares his knowledge on Husky Bites, a free, interactive webinar this Monday, September 14 at 6 pm EST. Learn something new in just 20 minutes, with time after for Q&A! Get the full scoop and register at mtu.edu/huskybites.

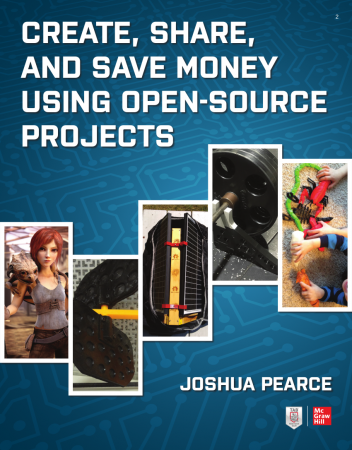

Want to know how you can save money, even make money, by turning your household waste into valuable products? Well, you’ve come to the right place. Professor Joshua Pearce and alumna Megan Kreiger, will cover the exploding areas of distributed recycling and distributed manufacturing. They’ll also explain just how using an open-source approach enables the 3-D printing of products for less than the cost of sales taxes on commercial equivalents.

3-D printing need not be limited to household items. In other words, don’t be afraid to think big—like the whole house! Kreiger’s team was the first to 3-D print a building in the Americas and last year they 3-D printed a 32-foot-long reinforced concrete footbridge.

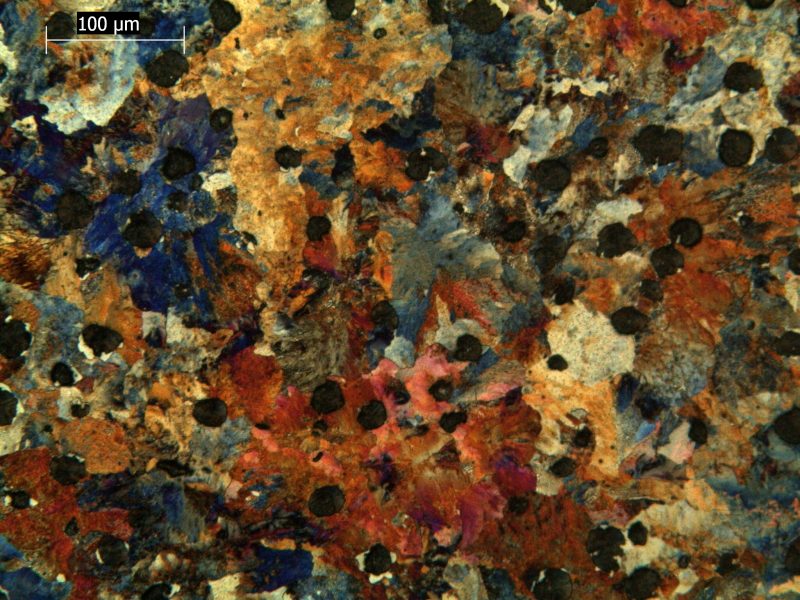

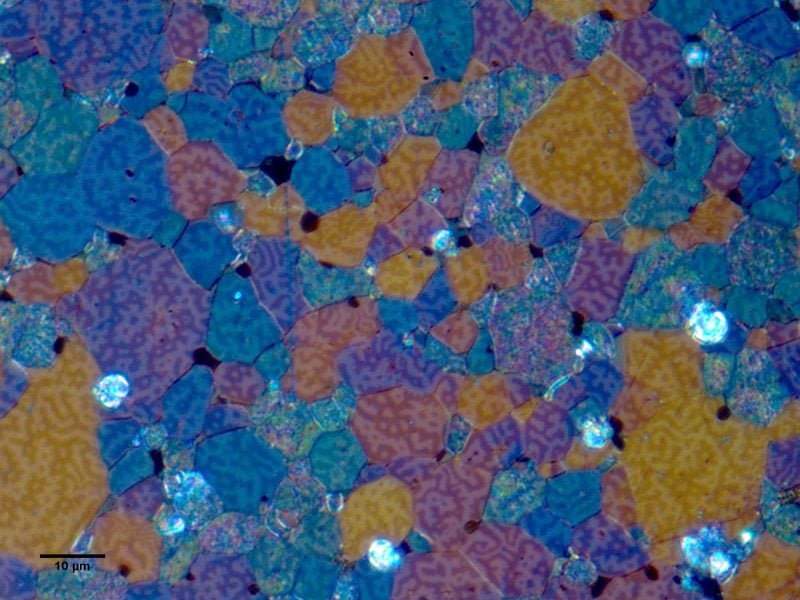

Yes, you can 3-D print concrete, in addition to plastic and metal.

Kreiger was Pearce’s very first Michigan Tech graduate student. She earned her BS in Math in 2009, and her MS in Materials Science and Engineering in 2012, both at Michigan Tech. She is now Program Manager of Additive Construction at the US Army Engineer Research and Development Center.

Kreiger says she first became aware of 3-D printing at Michigan Tech, while working in Pearce’s 3-D printing lab. She worked with Pearce to show that distributed recycling and distributed manufacturing were better for the environment than traditional centralized processes.

Pearce and his team of researchers in the MOST Lab (Michigan Tech Open Sustainability Technology) continue to focus on open and applied sustainability. As the Richard Witte Endowed Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, with a joint appointment in the Electrical and Computer Engineering, Pearce conducts research on photovoltaics — the materials behind solar energy — as a means to generate power in regions of the world where electricity is unavailable or prohibitively expensive. His research is also internationally renowned for its work in open source 3-D printing in order to enable both individuals as well as underserved regions to gain manufacturing capabilities.

The MOST Lab, a cornerstone of Michigan Tech’s open source initiative, fosters strong collaboration between graduate and undergraduate researchers on campus—and with vast open source international networks, visiting scholars and industrial partners. Currently, most 3-D printing is done with virgin polymer feedstock, but research conducted by Michigan Tech’s MOST lab has shown that using recycled 3-D printing feedstock is not only technically viable, but costs much less, and is better for the environment.

Pearce is the advisor of the multidisciplinary, student-run Open Source Hardware Enterprise, part of Michigan Tech’s award-winning Enterprise Program. Dedicated to the development and availability of open source hardware, the Enterprise team’s main activities: Design and prototype, make and publish—and collaborate with community.

Professor Pearce, when did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

It happened just as I began to choose what type of graduate school to pursue. I was a physics and chemistry double major at the time. One of my close friends, a physics and math double major, claimed he never wanted to work on science with an application. As for me, I was painfully aware of the enormous challenges facing the world, challenges I believed could at least partially be solved with applications of science. That day my career trajectory took a definite tack towards engineering.

Family and Hobbies?

I live with my wife and children, all consummate makers, in the Copper Country. Old hobby: when flying, picking out how many products I could make for almost no money from the SkyMall catalog. New hobby: sharing how to do it with other people.

Megan, when did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

Throughout high school I had a profound love of mathematics. I took every math class I could, and graduated a semester early. This love of mathematics drove me to engineering. I started my undergraduate degree in 2004, but switched over to Mathematics after an injury and a bad-taste-in-my-mouth experience during a summer engineering job. I graduated during the recession of 2009 and after one year off, decided to return to Michigan Tech for my graduate degree. I had an interest in recycling and earned an MS in Materials Science and Engineering while obtaining a graduate certificate in Sustainability. That’s when I fell in love with 3D printing. My passion has evolved into the union of materials science and additive manufacturing. I push the bounds and perceptions of large-scale additive manufacturing / construction.

Hometown, Family and Hobbies?

I grew up in rural Montana with my brother, raised by eco-friendly parents. At Michigan Tech while pursuing my degree, I spent her time hiking, snowboarding Mont Ripley, and backpacking the 44 miles of the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore with my husband. We now live in Champaign, Illinois, with our two children and our three at-home 3D printers. We spend our time raising chickens, wrangling pets (and kids), and working to modernize the construction industry for the US Military through the integration of concrete 3D printers.

Read more:

MTU Engineering Team Joins Open-source Ventilator Movement

Q&A with the MTU Masterminds of 3D-printed PPE

Just Press Print: 3-D Printing At Home Saves Cash

Power by the People: Renewable Energy Reduces the Highest Electric Rates in the Nation