The Graduate School announces the recipients of the Doctoral Finishing Fellowships, KCP Future Faculty/GEM Associate Fellowship, and CGS/ProQuest Distinguished Dissertation Nominees. Congratulations to all nominees and recipients.

The following are award recipients in engineering graduate programs:

CGS/ProQuest Distinguished Dissertation Nominees:

Doctoral Finishing Fellowship Award:

- Alejandra Almanza, Materials Science and Engineering

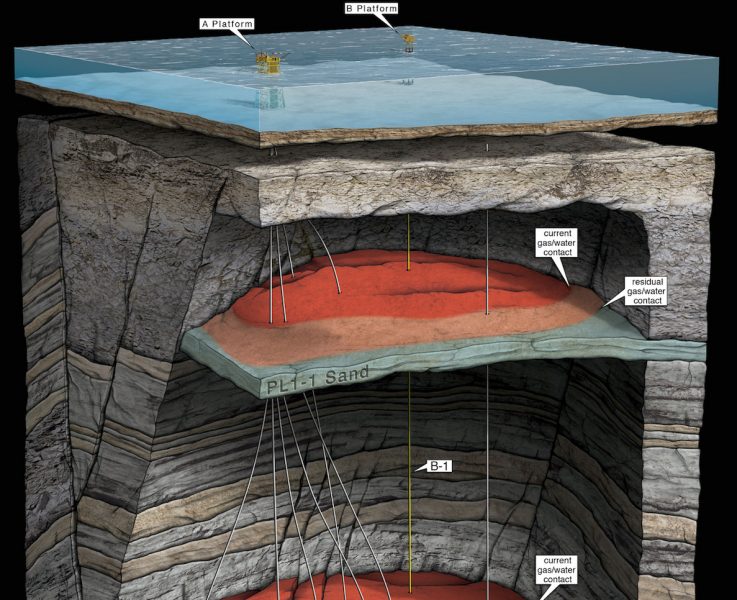

- Chandan Kumar, FNU, Geological Engineering

- Esmaeil Dehdashti, Mechanical Engineering-Engineering Mechanics

- Yuesheng Gao, Chemical Engineering

- Srinivas Kannan, Biomedical Engineering

- Sergio Miguel Lopez Ramirez, Civil Engineering

- Kevin W. Sunderland, Biomedical Engineering

- Xiaodong Zhou, Civil Engineering

Profiles of current recipients can be found online.