I have mentioned before the old canard that there are two seasons in the Upper Peninsula: Winter’s Here and Winter’s Coming. While this obviously does not do justice to our beautiful summers, there is definitely a Winter’s Coming season, and it just arrived. After a rather late, warm, and wet fall, we had a storm blow through here on Tuesday with cold rain and 50-60 mph winds that was like a shot across the bow. Although the landscape is still dotted with a few bright yellow trees that weren’t quite ready to quit, for the most part our woods are bare. The forecast now includes rain/snow mix and other reminders of what’s to come. It’s the time when we put the driveway stakes in the ground, tune up the snowblowers, and make sure our snowplowing contracts are in place.

I have mentioned before the old canard that there are two seasons in the Upper Peninsula: Winter’s Here and Winter’s Coming. While this obviously does not do justice to our beautiful summers, there is definitely a Winter’s Coming season, and it just arrived. After a rather late, warm, and wet fall, we had a storm blow through here on Tuesday with cold rain and 50-60 mph winds that was like a shot across the bow. Although the landscape is still dotted with a few bright yellow trees that weren’t quite ready to quit, for the most part our woods are bare. The forecast now includes rain/snow mix and other reminders of what’s to come. It’s the time when we put the driveway stakes in the ground, tune up the snowblowers, and make sure our snowplowing contracts are in place.

The change of seasons coincides as it often does with a change in the vibe in the ECE office. For some reason, it seems that the first half of the fall semester is just frenetic, with one deadline after another and lots of visitors who like to come to campus during that short window of time when the fall colors are at their peak. This year was made even a little more hectic with our ABET accreditation visit earlier this week. (I’m not supposed to tell you how that turned out, so I won’t.) Now all of a sudden it feels like we can take a little bit of breather. More importantly, we can turn our attention to some important longer-range issues that keep getting putting off on those days when all one thinks about is the agenda for tomorrow’s meeting.

The biggest long-range project on my plate this year is leading an effort to look at the role of computing at Michigan Tech. Before describing that further, I should give some context. This year we are looking at a major transition in the leadership at Michigan Tech, with ongoing searches for the president and the deans for four out of our five academic units: the College of Engineering, the College of Sciences and Arts, the School of Technology, and the School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science. This is not the result of any crisis, but just a bizarre coincidence where everyone hit retirement age at about the same time. The “last man standing” is Dean Johnson from the School of Business and Economics (whose first name really is Dean, leading to no end of jokes and explanations.) While it is difficult to predict exactly what will happen, I think it is safe to say that Michigan Tech will look a lot different at this time next year.

Back to the computing initiative. For many years, a number of people, both on-campus (including me) and some key external advisors have been looking at Michigan Tech’s position with regard to computing and information sciences, and wondering what we can do or should do to elevate our impact and our visibility in this key technology area. For several years now I have been a part of the Alliance for Computing, Information, and Automation (ACIA) which brings together the ECE Department, the Department of Computer Science, and the School of Technology, as we look for ways to cooperate in our academic programs and collaborate in research. The most successful outgrowth of that partnership has been the establishment of the Institute of Computer and Cybersystems, a research center led by CS department chair Min Song. However, there is more to be done, and with the upcoming transitions at Michigan Tech now is the time to do it.

In April of 2017 I made a presentation to the Michigan Tech Board of Trustees on behalf of the ACIA, where we made the case that computing is a key technology driver in the 21st century and that Michigan Tech should have a larger presence in order to stay true to its mission. With the encouragement of the Board of Trustees, this was followed up with a Computing and Information Sciences retreat on August 18, led by Provost Jackie Huntoon, where more than 60 member of the Michigan Tech community came together for a day and got a lot of issues out on the table. There was an excellent keynote address by Michigan Tech alumnus and benefactor Dave House, really driving home the point that the world has changed and that Michigan Tech needs to be paying attention. The retreat was a success, I believe, for raising awareness and getting people to think about what we might do. Of course, there were as many ideas about that as there were people in the room.

This brings us to present. Provost Huntoon has formed a Computing and Information Sciences (CIS) Working Group and asked me to lead it, and of course I jumped at the opportunity. The other members are: Min Song (CS), Jim Frendewey (SoT), Laura Brown (CS), Tim Havens (ECE/CS), Roger Kieckhafer (ECE), Myounghoon Jeon (CLS/CS), and Benjamin Ong (Math). Our charge is to use the time we have this year to develop recommendations designed to promote growth in size and quality of the degree programs and the University’s research portfolio in computing and information sciences, in the broadest sense. The recommendations are due to the Provost prior to the end of the 2017-2018 academic year. She will review those recommendations and use them to provide guidance to the future University president and the University’s Board of Trustees. Throughout the year we will periodically engage with a broad-based Advisory Group to share ideas and receive feedback. We have already gotten started, but now that some of the early-semester tasks are behind us I hope to really gather some momentum.

Most likely the topic of computing and information sciences at Michigan Tech will be the theme for this column, for much of the rest of this semester. The reader might wonder why I led off this story with a description of the change of seasons in the Upper Peninsula, which on the surface sounds a little ominous. You have to understand: I love the winters here at Michigan Tech. I am energized by the snow and all the winter sports that come with it. For me, this is not a time of hibernation, it’s a time of joy and rejuvenation, even during the shortest days and the darkest nights. I hope to bring some of that enthusiasm to the important task before us, and if we make any progress you will read about it right here.

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University

Last weekend Michigan Tech was privileged to host Silicon Valley entrepreneur and writer Martin Ford, author of the NY Times bestseller Rise of the Robots, which is all about the disruptive changes in the recent past and future in the areas of robotics, control, and automation, and the implications for our society and our economy. I was able to join Mr. Ford for a couple of different question-and-answer sessions with interested faculty, and to attend his presentation at the Rozsa Center which was open to the general public. I found the entire day to be stimulating and compelling, and I was very happy about the fact that Career Services and the Rozsa Center were able to work together and pull this off. The evening presentation was very well attended and included a lot of students. I was impressed that so many people were willing to give up their Saturday to hear a PowerPoint presentation about automation – but it really was that good.

Last weekend Michigan Tech was privileged to host Silicon Valley entrepreneur and writer Martin Ford, author of the NY Times bestseller Rise of the Robots, which is all about the disruptive changes in the recent past and future in the areas of robotics, control, and automation, and the implications for our society and our economy. I was able to join Mr. Ford for a couple of different question-and-answer sessions with interested faculty, and to attend his presentation at the Rozsa Center which was open to the general public. I found the entire day to be stimulating and compelling, and I was very happy about the fact that Career Services and the Rozsa Center were able to work together and pull this off. The evening presentation was very well attended and included a lot of students. I was impressed that so many people were willing to give up their Saturday to hear a PowerPoint presentation about automation – but it really was that good.

Ford’s basic premise was twofold. First, although there have always been concerns raised about changes in employment and the economy due to technological advances, going all the way back to the Luddite movement in 1811, this time things are different due to the nature of the technological advances themselves, primarily in the area of artificial intelligence and deep learning. Second, there has been a marked shift in the relationship between worker productivity and worker compensation, that has led to increased inequality and that will probably continue into the foreseeable future.

The argument that “this time it’s different” centers around the sudden relevance of artificial intelligence and machine learning in engineered systems. Artificial intelligence has been around a long time, and for most of that time I have thought of it as the technology of the future – always has been, always will be. Now, in the past 5-10 years or so, it is becoming the technology of the present. This is due to a couple of factors. One is, the raw computing horsepower needed to carry out artificial intelligence calculations is starting to become a reality, due to the inexorable march of Moore’s Law (which says that, essentially, computing power per unit area on integrated circuits doubles every 1.5 to 2 years.) The second is the algorithms themselves, which have been steadily improving in academic research labs for many years, and which are now getting a turbo boost of innovation in industrial research labs like those of Google and Facebook, who recognize the importance to their bottom line. As evidence that we have turned a corner in artificial intelligence, Ford and many others love to point to the IBM Watson 2011 victory in an exhibition match of the TV game show “Jeopardy” over two human champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. More recently, a program called AlphaGo was developed by Google DeepMind in London to play the enormously complex game of Go, and in May of this year it defeated the No. 1 player in the world in a 3-game match in Wuzhen. What is particularly interesting about AlphaGo is that it is not based on a set of rules or heuristics, but rather it simply (perhaps not so simply) trained itself to play the game through a process of trial and error using the techniques of machine learning. This whole field of “deep learning”, based on artificial neural networks made bigger and better as a result of Moore’s Law, is taking Silicon Valley by storm and has really transformed the economic focus there from electronics to software.

[Aside: I have always maintained that the IBM Watson Jeopardy match was not a fair fight. To make it fair, the entire computing platform and its database would have to fit into a box no bigger than 1500 cubic centimeters, consume no more than 20W of power, and be silent when others are speaking. Watson was a very large computer consisting of multiple servers in a separate room with a very loud air conditioning system, and it had access to huge databases of information. Human players are not allowed to “phone a friend” during the match. The counterargument, I suppose, is that the human players had the advantage of 30+ years of training.]

The starting point for Ford’s argument on the economic disruption of automation is in the relationship between worker productivity and worker compensation. In what is considered by the many the “golden age” of American manufacturing, post-WWII, advances in tools and technology allowed workers to become more and more productive, according to a metric of goods and services produced per unit time. As a result, workers became more and more valuable and thus wages went up in lock-step with productivity. Sometime in the mid-1970s, however, this coupling was broken. Worker productivity continued to go up and up, but wages became flat. Ford often made the statement that, adjusted for inflation, American workers have not received a raise in 40 years. He attributes this to a shift from a situation where tools helped human workers be more productive, to a situation in which tools can simply replace the human workers. The situation continues to this day, and the outlook is for it to continue even more rapidly, leading to greater levels of income and wealth inequality and hence social disruption.

Asked whether he was an optimist or a pessimist, Ford responded that he was a pessimist in the short term, based on the realities on the ground, but that he is still an optimist in the long term when he thinks about human resilience and ingenuity. There are some serious problems we are going to have to come to grips with, but if we can work together to recognize and solve those problems, and maybe even get out in front of them, then there is still hope. He is realistic, but not all doom and gloom. I did find his approach different, and more down to earth, from that of other futurist authors I have read lately, some of whom are wildly optimistic about the future of the human race and its relationship to the machines we are creating.

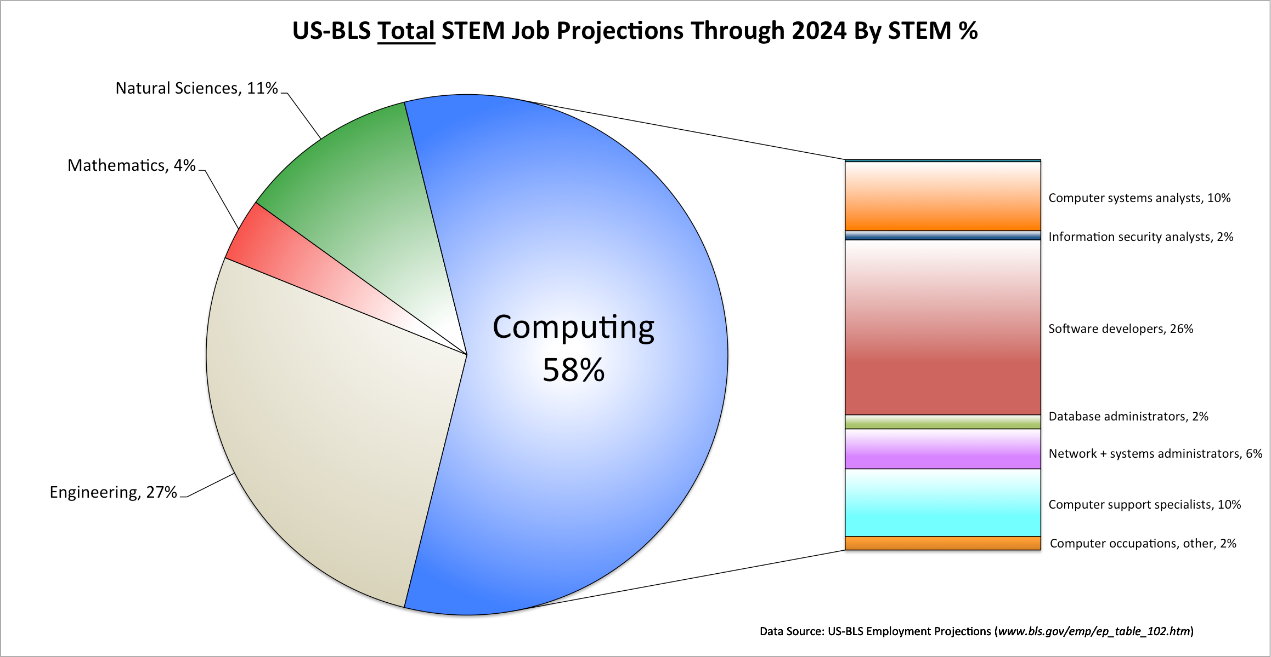

I found myself nodding in agreement with most of the Ford’s points, and had my own takeaway messages. The first is, and I realize this may sound a bit selfish, this is a fantastic time to be an electrical or computer engineer or computer scientist, about to be entering those fields. The technologies of robotics, control, and automation are advancing rapidly, and the advances are not about to stop. We are the ones who are creating this technology, and thus we are the ones who are going to be in demand in the next few decades. Ford himself, knowing that he was at a technological university, made a couple of offhand remarks to the effect that “you guys are going to be OK for a while.” Those who are losing out socially and economically could say that we are part of the problem, and they may very well have a point, although I think as well-educated problem solvers there is every reason to think we can be part of the solution as well. But, setting that aside for a moment, from the individual point of view I would have to say that I cannot imagine a better career to be considering right now than something in the intersection of EE, CpE, and CS.

As evidence of that I would point to our very own Career Fair, which was held this week. Over 340 companies were on campus recruiting Michigan Tech students for co-ops, internships, and full-time. My friends over in Career Services tell me that everybody – everybody – is looking for more electrical engineers and computer engineers. We cannot fill the demand right now of all the companies looking to hire our students. This story is reflected also in national starting salary data. According to the Spring 2017 report of the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) which covers hiring of the Class of 2016, the top starting salaries by major in the nation, for groups with sample sizes of 500 or more, were:

Computer Science $78,199

Computer Engineering $74,439

Electrical Engineering $70,950

In the interest of full disclosure, Petroleum Engineering and Operations Research were higher, with sample sizes of 184 and 64 respectively. Petroleum Engineering used to be much higher, like over $100,000, but that has come way down and is now comparable to Computer Science.

These salary numbers are echoed locally. According to our Career Services 2016 Annual Report, Michigan Tech electrical and computer engineers (which were lumped together) had a 99% placement rate and an average starting salary of $65,951, which was highest among majors in the College of Engineering. ECE was second only to Computer Science, which did very well with an average starting salary of $78,333. The ECE figure is lower than the national average, but it is worth pointing out that many of our graduates take positions in the upper Midwest which has a lower cost of living than California. Our starting salaries are very close to what is reported in the NACE survey for the Great Lakes Region: EE $65,815 and CpE $67,610. Our Career Services numbers are self-reported and must be taken with a grain of salt; nevertheless there is no question in my mind that our graduates are doing very well. I never hear complaints otherwise.

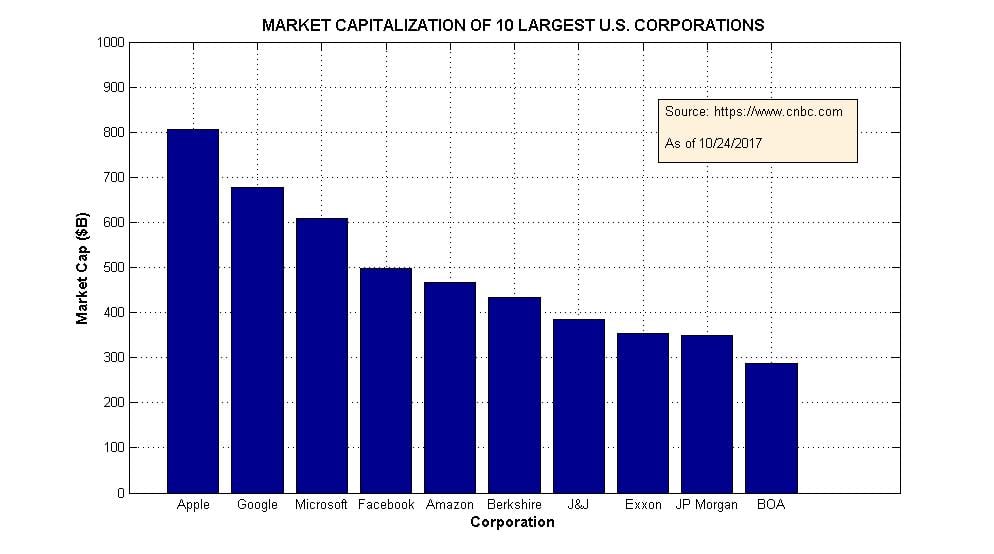

A second point I want to make that was sparked by Martin Ford’s presentation, although tangential to his primary message, has to do with the ascendancy of the overall field of computing relative to engineering. He said it right out of the gate, that all the action in Silicon Valley right now is in artificial intelligence and deep learning. Silicon Valley got its name and its reputation from the design and manufacture of integrated circuits, but that is now taking a back seat to software engineering. The four U.S. corporations with the largest market cap right now are Apple ($791B), Google/Alphabet ($662B), Facebook ($490B) and Amazon ($459B). Apple still manufactures products, and Amazon manages a massive product distribution system, but even so the backbone and the core competency of these companies is essentially software. There are areas where software engineering intersects traditional engineering, to be sure, and the most visible example of that right now is in autonomous vehicles. The reason that Google can get into this game in the first place is that they do not have to design the power train. The value added by taking a traditional vehicle and making it autonomous comes from a suite of sensors, a trunk full of computing hardware, and all the cognitive data processing and artificial intelligence algorithms that end up controlling the accelerator, the brakes, and the steering. I predict that over the next 10-20 years we are going to see a lot more of these systems where the technological advances are primarily on the computational side, not on the physical side. I also believe that we need to be doing more to prepare our engineering students for a world that will be dominated by computing and software, and I will have much more to say about that in future columns.

Clearly my two take-away messages above were not really what Martin Ford came to talk to us about. In the end he advocated for a couple of things. One was more education in the social and economic impact of robotics and automation, which is certainly something I support and which would make all the sense in the world as part of our general education program. The second was starting a conversation around the idea of a guaranteed universal income. I think he is an proponent for this idea, but he recognizes the enormous political challenges and was content on this trip just to get people to start thinking about it. So, I am starting to think about it. I’m not ready to jump up and down arguing on either side, but am willing to learn more and have the conversation.

Fall is coming slowly to the Keweenaw this year. It’s been a wet summer and fall, so the colors should be pretty good as long as we can get a good cold snap to bring them out. Not seeing that in the forecast yet. Have a great weekend everyone!

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University

This weekend Michigan Tech welcomes a special guest to campus. Martin Ford, Silicon Valley entrepreneur and author of the bestseller Rise of the Robots, will be here tomorrow to spend a day with faculty and students, and to give a presentation that is free and open to the general public. That’s Saturday, September 23, at 7:30pm, in the Rozsa Center for the Performing Arts, for those that are nearby and interested. I plan to spend a fair amount of time with Mr. Ford, both socially and as part of his schedule of speaking events, and am looking forward to that. Since I see robotics, control, and automation as a important strategic growth area for the ECE Department, I thought this would be a golden opportunity to share some thoughts on the topic. It also makes sense to put those thoughts together after this weekend’s activities, not before. Until then, Happy Autumnal Equinox and have a great weekend!

This weekend Michigan Tech welcomes a special guest to campus. Martin Ford, Silicon Valley entrepreneur and author of the bestseller Rise of the Robots, will be here tomorrow to spend a day with faculty and students, and to give a presentation that is free and open to the general public. That’s Saturday, September 23, at 7:30pm, in the Rozsa Center for the Performing Arts, for those that are nearby and interested. I plan to spend a fair amount of time with Mr. Ford, both socially and as part of his schedule of speaking events, and am looking forward to that. Since I see robotics, control, and automation as a important strategic growth area for the ECE Department, I thought this would be a golden opportunity to share some thoughts on the topic. It also makes sense to put those thoughts together after this weekend’s activities, not before. Until then, Happy Autumnal Equinox and have a great weekend!

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University

Today is the last day of our first week of the fall semester, and students are already getting their first break from classes. Later today is K-Day (short for Keweenaw Day), an outdoor event with food, music, and lots of practical information about activities at Michigan Tech, held at McLain State Park, on the shores of Lake Superior about 10 miles from campus.

Today is the last day of our first week of the fall semester, and students are already getting their first break from classes. Later today is K-Day (short for Keweenaw Day), an outdoor event with food, music, and lots of practical information about activities at Michigan Tech, held at McLain State Park, on the shores of Lake Superior about 10 miles from campus.

The weather for K-Day promises to be absolutely beautiful, which is in contrast to the cool, rainy weather that we have seen recently. We joke a lot about our “reliable crummy weather” but in truth things here are pretty benign, and I even include our winter snowfall in that statement. We have nothing that compares with the devastation caused by Hurricane Harvey in SE Texas, or Hurricane Irma which has wreaked havoc in the Caribbean and is bearing straight down on Florida. I’ll take the rain any day over the drought in the western U.S. which has led to practically apocalyptic wildfires that are barely making the news. My daughter, a college student in Bellingham, Washington, came home to visit this week, and as she got off the plane she remarked that this is the first time she has been able to breathe clean air in days. So, we count our blessings, and of course our hearts go out to all our fellow citizens whose lives are being negatively impacted by these weather events.

This weekend I hit a personal milestone – my 60th birthday is this Sunday, September 10. It is not really an accomplishment of any sort, other than just having lived this long, but I plan to celebrate nonetheless. I have never been shy about birthdays, and am not one of those people that tries to ignore the fact that I am a year older. Party on, that’s what I say!

I understand that a person’s 60th birthday is a major life event in Chinese culture; it has something to do with the 12 years of the Chinese zodiac and the belief that going through that cycle five times represents the completion of an even larger cycle (I defer to my Chinese friends and colleagues for a better explanation.) When my PhD advisor, Prof. Bede Liu of Princeton University, had his 60th birthday, a bunch of his former PhD students organized a big surprise party and people flew in from all over the country to celebrate with him. We even held a mock PhD oral qualifying exam for him, with former student Dave Munson (later Dean of Engineering at the University of Michigan, now president of Rochester Institute of Technology) presiding. That was 23 years ago, and Bede is still going strong. Coming up on this weekend brings back fond memories of Bede and how I still reach out to for him for advice on major life decisions – like a marriage proposal in 1994, and coming to Michigan Tech in 2008.

As is often the case with milestones in life, this is a good time to look forward with optimism and resolve. This academic year I am starting my 10th year at Michigan Tech, and my 4th 3-year term as department chair in the ECE Department. I feel reasonably confident that I still have something to offer, and am eager to do what I can to help move the department and the university in the right direction. This is not to say there is no room for improvement! Most of what I have learned about university administration I have learned on the job, and I am still learning. I have gotten a lot of very good advice over the years from colleagues and mentors, notably the namesake on my professorship Dave House. Dave is fond of saying “Experience is something you get right after you need it” and I have seen that play out many times.

I have also seen the importance of clear, concise communication in my position, and so I greatly appreciate the keynote presentation we had yesterday evening for all the first-year engineering students at Michigan Tech, given by Libby Titus, a Michigan Tech Environmental Engineering alumna and a technical communications expert at Novo Nordisk. Her topic was the importance of communications skills, particular writing skills, for professional engineers. I thought all of her points and her advice were spot-on. One point that she made is that the technical skills acquired in engineering school, as difficult and challenging as they seem to students at the time, are in retrospect easy compared to all the interpersonal skills that are required in the workplace. Communication skills are particularly important, and people who are effective in communication are the ones who will reach a large audience with their brilliant technical ideas. “Engineering and science are group activities” was a phrase she repeated a few times. I especially appreciated the point she made about the importance of using correct grammar in all forms of written communication. Readers of my “Rants from the Grammar Maven” column from earlier this summer can imagine me nodding in violent agreement during that part of the talk.

As much as I agree with what was said at the talk yesterday, I will counter with one point. We have a lifetime to acquire interpersonal, management, and leadership skills as we mature, but the best time to learn math, science, and engineering is when we are young. So to all our engineering students in attendance yesterday, I would say that our speaker was 100% correct in everything she said, but don’t let that stop you from getting your geek on while you are here at Michigan Tech. This is the place to become the technical expert you want to be, or at least to get started in that direction. Yes, you need to be a good communicator, but you have to have something to say, and the best way to do that is become a great engineer first. This is the old “build your house on rock, not on sand” argument that I have used before. Our educational programs in engineering are set up to help you succeed as technical experts, and all the feedback we get from alumni and industry partners tells us that our approach based on strong fundamentals works. In other words, enjoy K-Day, but be ready to hit the books next Monday!

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University

Greetings to everyone from the chair’s office in the ECE Department! Here we are again, at the cusp of a new academic year at Michigan Tech. The new students have already been on campus for a week, for orientation, and classes start next Tuesday. As much as I love the beautiful quiet summers here, I get energized by the new and returning students, the new faculty members across campus, and the overall “buzz” of activity that accompanies the new year. Game on!

Greetings to everyone from the chair’s office in the ECE Department! Here we are again, at the cusp of a new academic year at Michigan Tech. The new students have already been on campus for a week, for orientation, and classes start next Tuesday. As much as I love the beautiful quiet summers here, I get energized by the new and returning students, the new faculty members across campus, and the overall “buzz” of activity that accompanies the new year. Game on!

One little indicator of the increased level of activity is the increase in my e-mail. I have a nerdy little system where I track my e-mail pretty carefully, in an effort not to lose or overlook stuff, and part of that includes jotting down the number of e-mails in my inbox over every 24-hour period. Over the summer, right up until last Friday, that number was just under 100 e-mails per day. Starting this past Monday, that number jumped up to an average of 143 per day – a 43% increase! Not all of those required immediate action on my part, thank goodness. Our provost, Jackie Huntoon, tells me that she processes around 400 e-mails a day, and I don’t know how she does it. If one can handle 100 messages an hour, which is about my pace, that means spending half the day just conducting business by e-mail. I do notice that on those days where I am sitting in my office sending out e-mails to everyone, I end up with a lot more in my inbox. Funny how that works. Elon Musk, the entrepreneur behind Tesla and SpaceX, joked in an interview recently that e-mail was one of his “core competencies” although based on my experience I’m not entirely sure he was kidding.

Interested readers of FWF, if there are any, may notice that I kind of disappeared in the month of August. I don’t have much in the way of explanation, other than 1) I got busy, or 2) I got lazy. It actually was a busier August than usual. At any rate, I am back in the saddle and ready to share with you more random thoughts on a weekly basis as the semester progresses.

Today I will play “catch-up” with a few paragraphs about what has been on my mind the past month. Any of these topics could have turned into an entire column but I will try to keep it brief.

Alumni Reunions. Michigan Tech held its annual reunion celebration on campus in the first week of August. As always it was great to re-connect with so many Huskies from our past. For the second year in a row the pasty picnic was moved indoors to the MUB due to the threat of rain. Last year it was just that – a threat – but this year it rained cats and dogs so moving it was a good call. [My all-time favorite kid joke: “Hey, it’s raining cats and dogs!” “I know, I just stepped in a poodle.”] At the Friday night awards dinner, we gave the “Honorary Alumni” award to our good friend John Dau from DTE. This award is given to someone who is not an alumnus of Michigan Tech but who has been so engaged with the university that we can pretend he or she is anyway. That was a wonderful evening and I can’t think of a more fitting recipient than John. The entire week is a good opportunity to remind the alumni, and ourselves, that they carry the Michigan Tech “brand” with them their entire lives, and anything we do to move the university forward is a positive reflection on them, even when they have been away from campus for many years.

Copperman Triathlon. I bring this up just as an example of how wonderful it is to be in the Copper Country in the summer (see paragraph 1). The Copperman Triathlon is a very well-run local athletic event up in Copper Harbor, and I have enjoyed participating in it several times. It was held on August 5 this year. The distances are a little bit non-standard, but it is close to Olympic distance – 1/2-mile swim, 23-mile bike, 5-mile run. It can be done individually or in teams – I have done both – and this year I was on a team with Jesse Depue, daughter of retired Michigan Tech colleagues Chris and Carl Anderson, and Joan Becker, our very own Graduate Program Coordinator in the ECE Department. Our team name was “Trust Me, I’m an Engineer”. Jesse absolutely crushed it with a 13-minute swim, and Joan was flying on the bike at 1:12:30. I turned in a mediocre 47 minutes on the run, but hey, I was off the couch and enjoying a stunningly beautiful day in the Keweenaw. I’ll take it.

Charlottesville. From the sublime to the despicable. The events in Charlottesville really set me back and may have had something to do with why I just stopped writing for a couple of weeks, because I had such a hard time finding the words. It goes without saying, but I will say it anyway, that hatred, racism, white supremacy, Nazism, the KKK, and everything that goes with them and everything that they stand for are absolutely deplorable. What is more disconcerting to me is that there is even any debate about this. Seriously, how hard is it to condemn Nazis? There was no end of commentary to be found on social media, and two videos I really liked came from Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jim Jefferies. Schwarzenegger grew up in Austria, and in his video he commented on the soul-crushing effects of Nazism on those who served, and lost, in the German army in WWII. Jefferies, an Australian comedian and fairly recent addition to the Comedy Central line-up on cable TV, made a serious point about how we cannot pretend these neo-Nazis are not part of us (I will skip over his anatomical analogy, even though it was pretty good. Google it.) To his point, we as electrical engineers, computer engineers, and computer scientists have to come to grips with the fact that something we have created – the Internet – has a lot to do with the resurgence of hatred in our society. I have seen some of this stuff, and it is appalling to read what these cowardly little Internet trolls are saying about their fellow human beings under the cover of anonymity. I spend a lot of time here extolling the virtues of all the good things that electrical engineers have brought to this world. The Internet is one of those things, but it has a dark side that is way worse than anyone probably imagined 30 years ago. That hatred is now coming out into the open in ways that we are going to have to deal with, one way or another. I don’t have any good answers – I am just really worried.

Computing at Michigan Tech. Ah…coming back to the collective efforts of those who are actually trying to be a positive contribution to the planet. As we look forward to a season of leadership change here at Michigan Tech, with ongoing searches for the president and three deans, there are some who see a good opportunity for other types of changes as well. I am thinking particularly of change as it relates to computing and information sciences and how Michigan Tech will position itself in the years and decades to come. I count myself among those who would welcome a serious look at this issue. On Friday, August 18, Provost Jackie Huntoon convened a large group of stakeholders in computing at Michigan Tech for an all-day retreat where we explored a lot of different aspects of our approach to computing here. In attendance, and making two powerful presentations, was ECE alumnus Dave House, whom I have written about here before. Dave made the point that technology is changing rapidly in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and that Michigan Tech needs to adapt and be a leader in 4th IR technologies if we are to remain relevant. I couldn’t agree more. The whole point of the retreat was to open up hearts and minds to the possibility of change; no proposals were put on the table. This is going to be a long process, with lots of input from constituencies internal and external to Michigan Tech, and I have confidence that Provost Huntoon will guide that process effectively. This is something that is on my mind a lot these days, so you may be reading a lot more about it this year.

Personnel Changes. This year the ECE Department welcomes Dr. Tony Pinar as our new Lecturer and coordinator of the Senior Design program. I have asked Tony to concentrate this year on the quality and consistency of the student experience in Senior Design, and I know he will do exactly that. We also welcome Dr. John Pakkala, who will serve as our new Graduate Academic Advisor for course-option MS student. Both Tony and John hold PhDs from the department – Tony just last year under the direction of Prof. Tim Havens, and John many years ago under the direction of Prof. Jeff Burl. We are also dealing with the rather sudden resignation of Associate Professor Shiyan Hu, who has taken a chaired professor position at a university in Europe. I wrote recently about Shiyan’s exemplary professional service activity, and ironically it was this very activity that made him attractive for recruiting elsewhere. This is a blow for the ECE Department, but we congratulate Shiyan on his success and wish him all the best.

Well, I believe this brings us up to the present. We get one more breather, Labor Day weekend, before classes get underway next week. Make it a good one!

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University

Following up on posts earlier this summer about university teaching and research, I thought this week I would write a few lines about the third piece in the academic triumvirate – service.

Following up on posts earlier this summer about university teaching and research, I thought this week I would write a few lines about the third piece in the academic triumvirate – service.

Teaching, research, and service are often listed together as the responsibilities of a university faculty member. Research is all about the discovery of new knowledge and teaching is all about sharing that knowledge with the next generation. Service, in this context, refers to all the things that we do to maintain a healthy community and an environment where those first two activities can thrive.

Service activities are normally divided into two broad categories – university service and professional service. University service includes all the things that we do for our own institutions, beyond teaching courses and carrying out research projects. Professional service are all those things we do to maintain the professional communities outside of the university, often but not always centered around a shared interest in a particular area of research or scholarship.

University service is closely connected with the concept of shared governance, a principle which maintains that the faculty have an important voice in the academic programs and policies of the institution. Since we have a voice in those policies and programs, it is incumbent upon the faculty to exercise that right through participation in a myriad of committees and other governance bodies that either make recommendations to the university administration (in the case of policy) or have the authority to make decisions (in the case of academic programs and requirements). This can happen at multiple levels. In the department, we have faculty committees that oversee our undergraduate and graduate academic programs, organize seminars, manage our various communication activities, ensure compliance with accreditation requirements, maintain our laboratories and other departmental facilities. The faculty as a whole has the authority to vote on any changes to our academic programs, provided they are consistent with university-wide standards.

At the university level, at Michigan Tech we have a governance body, comprising both faculty and staff, called the University Senate. Each academic department has one representative, chosen by the departmental faculty, and there are some at-large members as well. The primary responsibility of the Senate is the oversight of academic programs: all new academic programs at Michigan Tech have to go through a rigorous Senate vetting process that the proposing departments consider onerous at the time but in the end plays an important and valuable role in quality control. The Senate also makes recommendations on non-academic matters that have an impact on faculty, staff, and students, such as the sabbaticals, benefits, and compensation. Most of the Senate meetings I have been to (usually because the ECE Department has some proposal up for a vote) are pretty boring but I am first to admit that the work is important and I thank all the representatives for their service. Saeid Nooshabadi has been the ECE rep for several years, and now that Saeid is off on sabbatical Chris Middlebrook is taking over this year.

Most faculty members are involved in some form of professional service outside the university, most often but not always related to technical areas of interest. Everyone on the ECE faculty (I’m pretty sure) is a member of the IEEE, the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, which incidentally is the largest technical organization in the world. The IEEE has a ton of activities related to the dissemination of technical information, including journals, conferences, and workshops. There are all sorts of ways to participate in those activities, such as being on technical committees, organizing workshops or sessions at conferences, or serving as an editor or associate editor for a journal. Generally speaking, I consider reviewing papers for journals and conferences as research activity and not service activity; something moves into the service category when there is more of an administrative function involved, such as being a conference organizer or a journal editor. That’s a subtle distinction and probably not all that important, although I do keep it in mind when doing faculty performance reviews.

There are lots of other professional organizations out there besides the IEEE, such as the American Society of Engineering Education (ASEE) and the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), and no end of opportunities to serve. Volunteers are rarely compensated for their time, but such service is expected of academic personnel, which in effect means that the universities that pay faculty salaries are footing the bill for all these professional organizations. That’s not meant to be a complaint; the organizations and the universities have consistent missions and as such, one could view the professional organizations as extensions of the entire university system taken as a whole. The system works as long as everyone does their part.

I often take advantage of this blog to brag on someone in the ECE Department, and today is no exception. One of ECE faculty members most active in professional service over the past couple of years is Prof. Shiyan Hu. Shiyan is an associate professor on the computer engineering side of the department, with interests in design automation and cyber-physical systems. He led the establishment of the new IEEE Technical Committee on Cyber-Physical Systems, whose membership includes 21 IEEE Fellows and 12 current or former Editors-in-Chief for IEEE or ACM Transactions. He is the co-Editor-in-Chief for the new journal IET Cyber-Physical Systems: Theory and Applications, and has established two new IEEE workshops, Cross-Layer Cyber-Physical System Security and Design Automation for Cyber-Physical Systems. Over the years he has been an associate editor for three different IEEE Transactions, and he has been a special issue guest editor for the five others, including an upcoming special issue of the IEEE Proceedings, on Design Automation for Cyber-Physical Systems (watch for it in 2018.) Shiyan is bringing a lot of visibility to ECE at Michigan Tech and we certainly appreciate it.

In these past few columns I have attempted to emphasize not only what we do in academics, but why we do it. In the case of service, I see service as being all about building communities. In many aspects of academics, there is an element of competition: departments compete against each other within universities, individuals compete nationally and internationally for priority and respect in their research, and universities compete with one another for prestige, with the most visible example of the latter being the rankings put forth by U.S. News and World Report. Competition is healthy for spurring innovation and motivating us to be the best that we can be, but it also has the unhealthy side effect of building walls and turning us against one another. Through our service activity, whether internal or external to the university, we have the opportunity to build communities of like-minded individuals who agree to support each other, and maybe even set the rules of engagement for orderly and fair competition. It gives us the chance to reflect on the fact that, at the end of the day, we really are all in this together. I believe that the balance between striving to be our best individually, while supporting each other to be our best collectively, is a beautiful thing about being in academics and one of the reasons that we stay in these positions for as long as we do.

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Michigan Technological University

FWF is taking a break this week, while my family and I visit Central Europe: Munich, Salzburg, Vienna, and Prague. Here is a photo of yours truly, looking like a typical American tourist, standing in front of the birthplace of Christian Doppler in Salzburg. Many of the readers of this column will know the importance of Doppler in radar signal processing.

FWF is taking a break this week, while my family and I visit Central Europe: Munich, Salzburg, Vienna, and Prague. Here is a photo of yours truly, looking like a typical American tourist, standing in front of the birthplace of Christian Doppler in Salzburg. Many of the readers of this column will know the importance of Doppler in radar signal processing.

Having a wonderful time – will be back next week.

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University

Happy New Year! Today marks the end of Fiscal Year 2017 at Michigan Tech, as it does for many other universities and businesses. This is the year boundary that really matters for anyone doing accounting or record-keeping at the university. For the past couple of weeks, a lot of staff members have been hard at work, making sure our financial house is in order. In July we will start the process of looking back at the past year, preparing year-end reports, and seeing how we did relative to a lot of different metrics. Of course, at the same time we are starting all over again with FY 2018. It’s the circle of life.

Earlier this month I offered some views on our fundamental motivation for being in this line of work – why we teach and why we do research. Today I thought it would be good to take a look at the interplay between teaching and research in the university setting.

In one of those earlier posts I made the observation that we are not a business, rather we are an institution that serves the public good and as such we have multiple stakeholders that we try to keep happy. That same notion about multiple stakeholders holds true at the individual faculty member as well, and if not managed properly it can lead to a lot of stress. In one sense the faculty members are accountable to only one person – me, the department chair – but in reality their performance depends in large part on keeping a lot of other people happy. On the teaching side, there are the students of course, one of our most important constituencies, and sometimes the parents, who generally only surface when things are not going well. There are also department colleagues, as we depend on each other to teach all the necessary prerequisite material for the next course or courses, to make sure a course plays its proper role in the overall curriculum, and to provide documentation needed for accreditation. In research, faculty are held accountable by their external program managers, who often do not understand that we have multiple obligations, by their national and international professional colleagues who provide anonymous peer review of the work, and by journal editors and conference organizers who expect timely compliance with paper reviews and other research-related activity. It’s a lot to juggle!

Even if we simply divide our activity into two broad areas, teaching and research, it can be a struggle to find the right balance between the two. They are often seen to be in conflict, two polar opposites competing for our attention. Students wonder why the faculty are wasting time doing research when they should be available 24/7 for questions and concerns. Research sponsors wonder why faculty are putting so much into teaching when they should be setting the world on fire with their latest scholarly achievements. Faculty members themselves are conflicted, feeling that they enjoy one activity while getting messages that they should spend more time on the other. Sometimes those are mixed messages, since at a place like Michigan Tech there are multiple gatekeepers for promotion and tenure, and there is the concern that different people have different opinions about what is important.

I believe that the answer to this conflict is not to see this as a conflict at all. Even though this is hard to pull off all the time, I still believe in the old-fashioned notion of the teacher-scholar, the person who has a high-level research or scholarly program in his or her own right, and is passionate about educating the next generation of students to make their own contributions to the field. This is really where the magic happens at a university. People who are brilliant scientists, engineers, mathematicians, or thinkers in any discipline, and are not jerks about it but instead really care about students and their education, are like gold at a place like Michigan Tech. The trick to making this work is to see that teaching and research are not pulling in opposite directions but are actually two sides of the same coin – the quest for new knowledge.

A strong research program can have a beneficial impact on one’s teaching. Sometimes we think that the teacher brings the results of his or her latest cutting-edge research into the classroom, keeping students current and motivated, but actually I do not think that is completely correct. Especially if we are talking about undergraduates, most cutting edge technology is beyond them – they are just not ready. After all, the faculty member has a head start on them by at least five years and probably more like 20 or 30. I think the real value of the research program, as it applies to teaching, is that it allows the teacher to know what is important and what is not in the fundamentals. In fact, it gives the faculty member the certainty that the fundamentals really are important, and that certainty will lead to clarity and passion. Sometimes we have to say “trust me, you really need to know this and you will thank me someday”. I get that that does not always work without some taste of good things to come. Here the faculty need to lead by example, demonstrating the kinds of things that can be accomplished if you follow their lead, without overwhelming students with details beyond their comprehension (the so-called “fire hose of knowledge.”)

The mutual benefits of teaching and research go the other direction too. Some of the key attributes of good teaching are, one has to be prepared, one has to be organized, and one has to communicate effectively. The discipline that comes with doing those three things on a regular weekly schedule can pay huge dividends in research programs, where often there is not the same pressure to break one big task down into lots of little tasks. The best teachers are the ones who know how to explain difficult concepts clearly, and clear communication goes hand-in-hand with clear thinking. I have often had the experience where just talking about some problem I am wrestling with leads to new and better ways of thinking about it. Put another way, in order to understand a problem one needs to be able to explain it well, and if you do not understand the problem chances are you are not going to understand the solution. Again, it all comes back to the fact that seeking knowledge and communicating knowledge are really not all that far apart; quite the opposite, they are complementary.

The way we learn things and the way we explain them are often quite different. When I think I know something pretty well, I can lay it out in a linear fashion: I say “here is concept A, which leads to concept B, which in turn implies concept C.” Mathematical proofs usually work this way. If I have been working on something for a while, and having some success, it is very satisfying to put things down in a neat set of notes with the proper flow of one idea into the next. The problem is, with 99% certainty that is not the way I learned the material. Usually I learn things in a more circular fashion, going forward and back and sometimes in random directions, figuring out bits and pieces and eventually figuring out how they are linked together. When the pieces are in place, and I want to convince someone of my results, then my explanation will be nice and linear. This is precisely how most of us organize our lectures and our courses: a nice logical flow from the beginning to the end. Actually I think this is perfectly acceptable. We just have to understand that our students, just like us, are not going to learn the material that way. Instead, they will get part of the lecture, then through homework, labs, and studying for tests they will go around and around in circles until it starts to make sense. Perhaps the goal should not be to have students comprehend a topic in that nice linear fashion from the very beginning, but rather to come to a linear understanding of that topic in the end. My point here is that this circular or random nature of discovery/learning, and the linear nature of understanding/explaining, are quite complementary and are mirrored in the way we do teaching and research.

Bringing this closer to home, I thought I would brag a little bit about one of our own. Tim Havens, an associate professor with a joint appointment in ECE and Computer Science, has found the sweet spot when it comes to balancing teaching and research. He is one of our most active researchers in the ECE Department, with a portfolio of funded projects in computational intelligence and signal processing totaling about $250k per year in research expenditures. He is the Director of the Center for Data Sciences, within the Institute for Computing and Cybersystems, and is also the Director of the non-departmental MS in Data Sciences professional degree program. As a teacher, he can cover just about anything in the computer engineering curriculum, from sophomore-level digital logic design to graduate-level machine learning, and he always gets outstanding student course evaluations. Having been to several of his recent graduate student thesis and dissertation defenses, I am impressed by the quality of his students’ work, and by the level of enthusiasm and camaraderie among the students in his research group. He is an outstanding example for all of us. Tim, feel free to use the comment feature of this blog if you want to tell us how you do it.

Next week is Fourth of July – have a safe and happy holiday!

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University

A very happy midsummer to all from the northern reaches of Michigan! This is the season for long days in the Keweenaw, and I thought it would be fun this week to explore some of the basic mathematical facts about sunrise, sunset, and the length of days, and throw in a little signal processing to boot.

First off, while the days are long this time of year, what makes them seem longer here is the timing of sunrise and sunset. Yes, we are pretty far north compared to most of the 48 contiguous states, but we are not really that far north. At 47 degrees N latitude, we are at about the same latitude as the northern tip of Maine, we are slightly south of Seattle, south of most of Canada and all of Alaska, and well south of all of Great Britain and Scandinavia. Our longest days in the summer are about 16 hours, and the shortest days in the winter are about 8 hours. There are plenty of places on the globe with greater variation in the length of day than that. The reason we think the days are so long right now is because of a quirk in the time zone map. Like all but three counties in the Upper Peninsula, Houghton County is in the Eastern time zone, despite the fact that we are slight west of Chicago, which is in the Central time zone. The story goes that we are on Eastern time so that we would be in the same time zone as the bankers and mine owners on the East Coast, 100 years ago. As a result, this time of year the sunset occurs around 9:50pm, and twilight extends for another hour or so after that. For those of us working at Tech and leaving around 4 or 5pm, it’s like another whole day to play outside.

This year the summer solstice occurred on Wednesday, June 21. While we often think of the solstice as a day, in fact it is a particular moment in time when the Earth’s axis of rotation is most tilted toward the Sun. At that instant, the axis of rotation is co-planar with the axis of revolution of the Earth around the Sun, and the Sun shines directly down on the Tropic of Cancer. This year the solstice occurred at 12:24am EDT, on Wednesday, July 21. The time of the summer solstice moves forward about 6 hours, or one quarter of a day, each year, as the period of revolution of the Earth around the Sun is about 365-1/4 days. The 1/4 day is why we have a leap year ever four years, and on those years the time of the summer solstice moves back 18 hours from the previous year. Oddly enough, part of the reason we say the solstice occurred on June 21 this year has to do with Daylight Saving Time; if we were on Standard Time the solstice would have occurred on Tuesday, June 20, at 11:24pm. As it turns out the longest day of the year, measured from sunrise to sunset, was actually June 20.

Here is a little-known fact which has fascinated me ever since I discovered it. The longest day of the year does not coincide with either the earliest sunrise or the latest sunset. At our latitude, the earliest sunrise occurs about 5 days before the solstice, and the latest sunset occurs about 5 days after. That means that, at the time of this writing, we have not even seen the latest sunset this year; that will occur on Sunday, July 25, at 9:54:06 p.m. The sunset time is not changing quickly, though: on both June 24 and June 26, sunset is at 9:54:05 p.m. Those who understand the basic concept from Calculus 101, that the slope of a function is zero at its maximum, will appreciate that.

The length of the day is defined as the time between sunrise and sunset, or if we want to do an arithmetic calculation, it is the sunset time minus the sunrise time. The addition or subtraction of two periodic functions that are synchronized in time is an important concept from the course I teach, EE1110, Essential Mathematics for Electrical Engineering. There we consider a particular class of functions, called sinusoids, and show that as long as two sinusoids have exactly the same frequency, then the sum or difference will also be a sinusoid, and furthermore there is a straightforward algorithm to figure out where the peaks and valleys of the sum (or difference) will be relative to the peaks and valleys of the signals being added or subtracted. In the case of the sunrise and sunset times, we already see that the earliest sunrise and the latest sunset are offset by about 10 days at our latitude, and that the longest day will occur somewhere in the middle.

Thinking there might be an interesting connection between electrical engineering and astronomy, I figured I would just go ahead and look at the numerical data in MATLAB and see if I could use it to illustrate EE1110 principles. There are lots of places on the Internet to find sunrise and sunset data times; here is one operated by the U.S. Navy: http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/RS_OneYear.php. What is nice about this site is that it provides the data for an entire year, in a format that is easy to cut and paste into an Excel spreadsheet. So, that is exactly what I did: I put the 2017 data into Excel, then imported it into MATLAB, then reformatted it so that times are expressed in minutes (from midnight) and kept everything in Eastern Standard Time. I also got rid of the months and dates, simply numbering the days sequentially starting with Day 0 being January 1, 2017. All of that took longer than it should have, but now I have the data conveniently in a .mat file.

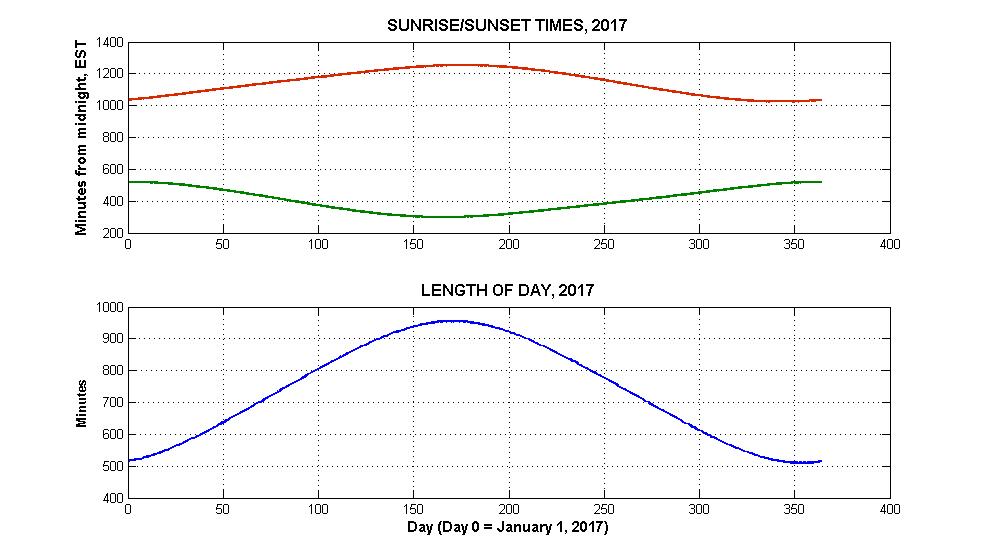

The upper panel in Figure 1 below shows the time of the sunrise (in green) and sunset (in red), measured in minutes from midnight, Eastern Standard Time, as a function of the day, for the entire year 2017. In the lower panel I show the length of the day (in blue), in minutes, which is simply the sunset function minus the sunrise function. For point of reference, one full day is 1440 minutes.

Here is where I got the first of three surprises in this little exercise. The sunrise and sunset functions are quite asymmetric, in the sense that they do not look the same when you flip them upside down. The latest sunset occurs after the summer solstice, whereas the earliest sunset occurs before the winter solstice, which means that the time from a peak to valley is considerably shorter, like 20 days, then the time from a valley to a peak. We see the same behavior in the sunrise data. Now the symmetry of sinusoids is important to a lot of the EE1110 theory, and because of the asymmetry issue we cannot use sinusoids to model sunrise and sunset data. Consequently, the idea of using sunrise and sunset times as an illustrative example of EE1110 concepts is out the window. Dang!

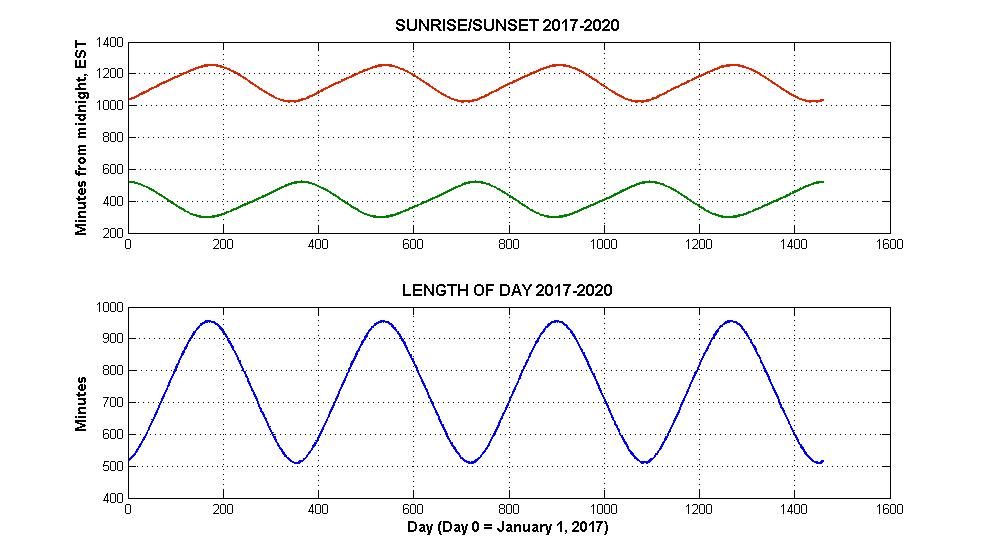

We are not done yet, however. As can be observed in the lower panel, the length of day function does exhibit symmetry, in fact it looks downright sinusoidal. So, I thought maybe we could throw some of our signal processing tools (well beyond the scope of EE1110) at this data and see if we can determine the period, or time for one complete cycle. To make this a little more accurate, I decided to look at four consecutive year’s worth of data, from 2017 to 2020. This data is shown in the Figure 2 below, which is essentially the same as Figure 1 except it goes for four years. To compute the period, or more precisely the frequency (the inverse of the period, in cycles per day), I used a common technique from signal processing of computing the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) of the data, using an algorithm called the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), and looking for the point at which the DFT reaches its maximum. For those following along at this point, I subtracted off the mean of the data, and zero-padded it out to 65536 data points before computing the DFT. Doing these kinds of calculations in MATLAB comes very easily to me after many years of signal processing research; it’s the kind of stuff I can sit at my desk and bang away and have it work right the first time.

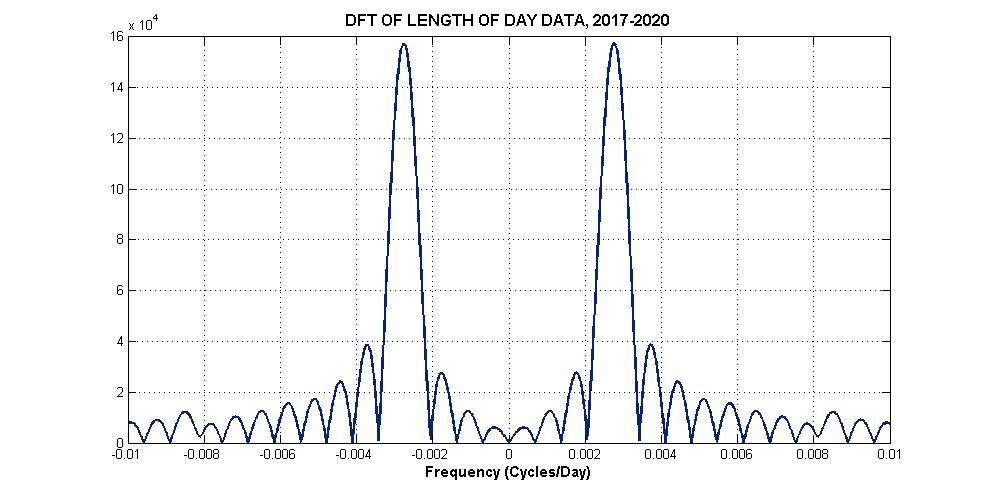

Except…I made a crucial mistake, and got the second surprise. The absolute value of the DFT of the length-of-day data is shown in Figure 3 below. The horizontal axis has units of frequency, in cycles/day. I was able to zoom in and find the frequency at which the DFT reaches a peak, and that value is 0.002762 cycles/day. 1 over this should be the correct period for one revolution, right? Wrong. 1/0.002762 = 362.06 days. I knew that can’t possibly be right – the period should 365.25 days. Where did I go wrong? It turns out I fell into a common trap (that I often rail against) of using the DFT without thinking carefully about the interpretation of the results. I had “known” forever that the best way to determine the frequency of a single sinusoid is to the compute the Fourier Transform and look for a maximum. That result is part of the collective wisdom of everyone in signal processing, and goes back at least to the often cited paper by D. Rife and R. Boorstyn, “Single Tone Parameter Estimation from Discrete-Time Observations,” IEEE Trans. Information Theory, September 1974. Well, I went back to that paper and found my error. Rife and Boorstyn consider the frequency estimation for a function called a complex exponential, sometimes called a complex sinusoid. (EE1110 students know all about complex exponentials, right?) For complex exponentials, computing the Fourier Transform and looking for a peak is exactly the right thing to do. However, a real sinusoid, like our length-of-day data, is actually the sum of two complex exponentials, one at a positive frequency and one at a negative frequency. The Fourier Transforms of those two complex exponentials can interfere with one another in such a way that the peaks can be shifted from what we would consider the correct location, in this case some 3.2 days (or the equivalent error in frequency). After some reflection I realized that the only way to really get the frequency right – that I could think of, anyway – is to do what is called nonlinear least-squares estimation, which essentially means looking exhaustively across all sinusoids for one that comes closest to matching the given data. Without going into too much more detail, I did exactly that for my length-of-day data and came up with a frequency of 0.002738 cycles/day, which corresponds to the period I expected, 365.25 days.

Last observation, and last surprise. I mentioned above that, before taking the Discrete Fourier Transform, I subtracted off the mean value. Out of curiosity, I went back and looked at that mean value; it was 734 minutes, or 12 hours and 14 minutes. Hold on, I thought – how can the average length of day be anything other than 12 hours? Every spot on the Earth enjoys equal amounts of light and darkness over one entire year, so the average has to be 12 hours, right? Again, wrong. Thanks goodness for the Internet. I Googled “average day length greater than 12 hours?” and hit on this beautiful little explanation: http://rickbradford.co.uk/DayLength.pdf. The author identifies three separate effects, but the largest and easiest to explain has to do with the non-zero diameter of the disk of the Sun, as seen from the Earth. We define sunrise and sunset as the moments when the Sun just appears or disappears over the horizon, but in fact it might be more accurate to define it as the moment when the center of the Sun disk crosses the horizon. That would bring more symmetry to the definitions of day and night, and shave a few minutes off the time we associate with day. Because of the nonzero diameter of the Sun, more than 50% of the Earth can see at least a portion of the Sun at any given moment, thus making the average length of day greater than 12 hours.

Make the most of these long days and the beautiful weather! The days are already getting shorter.

– Dan

Daniel R. Fuhrmann

Dave House Professor and Chair

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michigan Technological University