By Emily Riippa | University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections

What makes the college experience special? For some, it’s getting to dive deeply into studying what matters to them. For others, it’s the friends made over late-night study sessions, midnight adventures, or even more colorful escapades not to be described here. It’s forming a broomball team, setting off the fire alarm with burnt popcorn, pranking a buddy. Whatever it might be that sets college apart, the odds are good that the residence halls had a hand in it.

So many memories are formed in college dorms, and student housing at Michigan Tech is no exception. Over the years, a variety of residence halls have offered Huskies a place to sleep, study, and socialize on campus. Let’s take a look at three long-running dorms still serving students today: Douglass Houghton Hall, Wadsworth Hall, and McNair Hall.

Douglass Houghton Hall (DHH)

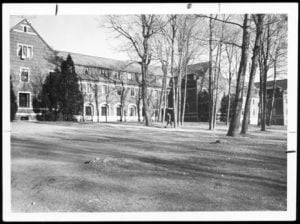

Douglass Houghton Hall, more commonly known these days as DHH, is the oldest residence hall at Michigan Tech. From day one, DHH stood out: it was the first building constructed as a dorm at the college and provided brand-new accommodations for some 204 male students when it opened in 1939. The following June, the hall received a formal dedication as Douglass Houghton Hall in a speech given by A.E. Petermann, the chairman of Tech’s Board of Control. This name, Petermann told his listeners, would remind the students that Houghton had made the most of his youth, achieving considerable success as a geologist, physician, and investor before drowning in Lake Superior at the age of 36.

In an article published in 1941, the Daily Mining Gazette sang the praises of DHH in rhapsodic terms to alumni arriving for that year’s reunion. The building was “of Tudor-othic style, and constructed of red brick, with stone trim, copper roof, and metal casement windows,” as well as solid local oak. Alumni and their guests would “appreciate particularly the lounge facilities,” of which there were two. “Mellow paneling, a large fireplace, davenports, reading-chairs, and a piano make each lounge a pleasant and homelike gathering place,” wrote the Gazette reporter. An infirmary, laundry, “student valet room,” kitchen, and dining room rounded out the offerings of DHH. Another article, this one in the campus paper, likewise noted that students could be buzzed to the hallway telephones; the luxury of room lines had not yet reached the dorm. From rooms facing the front of the building, lucky residents could look out at “a beautiful, tree-shadowed lawn,” in the words of the Gazette, and know that they were “but a stone’s throw from the college athletic field, and only a five-minute walk from the westernmost of the college buildings.” Best of all, students in the new dorm were not subject to a curfew, unlike their contemporaries at other colleges.

Of course, the relatively light supervision that DHH students enjoyed in those days was not always used wisely and well. In 1957, a pair of residents decided to transform their room into a chemistry lab, but their experiment ended with a minor explosion. Fortunately, the two were not seriously injured. On another occasion, a resident advisor asked a student to explain what had damaged a single globe light in his room. “A sonic boom,” the young man replied. The RA almost dismissed the incident on the basis of the student’s chutzpah. Then, of course, there was the time in 1951 that a group of students guided freshman Guenther Frankenstein’s massive Jeep up the stairs of DHH and parked it in front of Room 151. Fifty years later, Frankenstein recalled that the administration “wasn’t too happy regarding the event” and that the dean “wanted to expell [sic] me for good” but ultimately settled for a lengthy period of probation.

It cost the college $350,000 to build and furnish Douglass Houghton Hall. Unfortunately, despite the Gazette’s glowing reviews, the building quickly ran into issues. Insulation had to be added and the roof repaired within a year. Space also soon became a problem: in 1942, DHH housed 20 percent more students than it was designed to hold. World War II delayed construction of a new addition, which eventually opened in 1948. Some further renovations occurred in 1966, 1969, and 1991. Through it all, DHH has been a little historical gem in a campus looking to the future.

Wadsworth Hall

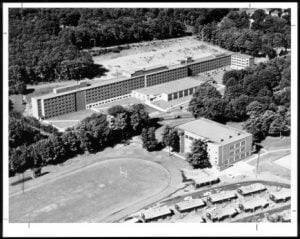

Wadsworth Hall is the longest dorm on campus, spanning more than a quarter mile on US-41. Ever since it first opened in the fall of 1955, “Wads” has attracted interest for its statistics. Writing about the dorm following a 1958 expansion, the Gazette noted that its construction required the removal of 100,000 cubic yards of excavated material, included 750 tons of reinforcing steel, and paid out $1.6 million in wages to the local community. Also remarkable was how dramatically the new residence hall expanded on-campus living: 70% more students could be accommodated in college housing.

Demand for dorm space at Tech was so high in 1955 that the first 356 residents moved in before their rooms were painted. Wads featured “ultra-modern living” in double rooms, each of which, the university boasted, featured a picture window, huge desk lights, and expansive closets with sliding doors. Common spaces also became a point of pride, including a sizable lounge and “a recreation room almost as large,” a ping-pong room, and a laundry room with all the trimmings. On the ground floor, Tech students needing medical care could visit the infirmary, which featured “five completely-equipped hospital rooms.” The Michigan College of Mining and Technology alumni magazine made a point to note that one of the rooms was “separated from the rest to serve the coeds.” The construction of the new Wadsworth infirmary relieved another building on campus, the Smith house, of its medical role, freeing up that building as residential space for women enrolling at Tech.

All of these amenities were housed in what is now just the eastern wing of the residence hall; the other portion, which included more student rooms and a dining hall, opened in 1958. Herman Gundlach, who had been the contractor on the second phase, submitted the successful bid for the final 200-bed expansion in 1965. Like historic DHH, Wads has also received its tune-ups over the years. The most ambitious of these took place in 2004, while students remained in residence. Remodeled shower stalls provided more privacy, and kitchens and lounges were extensively renovated. New carpeting and furniture moved into dorm rooms, replacing the much-applauded closets from the 1950s and building in lofts that students had come to love. Finally, the large dining hall received a “bright and modern look,” with “restaurant-style seating” replacing the “long, brown, institutional tables reminiscent of ‘Cool Hand Luke.’”

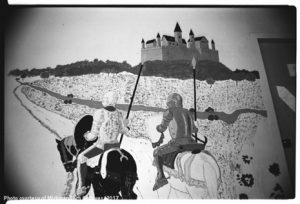

Residents of Wads before the renovation might recall one memorable way that their dorm-mates showcased their creativity in the building’s corridors. Beyond choosing imaginative names for their halls–which continues to this day–residents would paint murals in audacious style in celebration of their theme. The art coming out of the 1971 Winter Carnival was a good example: medieval scenes lined the hall that year, including an impressive painting of knights on horseback riding toward a castle. Who said that engineers couldn’t be artists?

McNair Hall

If you attended Tech in the 1960s through the 1980s, it might still seem odd to hear Co-Ed Hall referred to as McNair. Tech broke ground on the new dorm, which has since been renamed in honor of former college president Frederick Walter McNair, in December 1965. McNair as we know it, however, almost didn’t happen at all. In the early 1960s, with enrollment of students and especially of female students (“co-eds”) steadily increasing, the college found itself facing a housing crunch. It needed on-campus rooms for women, so administrators set aside a number of spaces in Wads. That provided only a temporary remedy to the problem, as students asking for campus housing continued to enroll. Tech went to the drawing board and came up with a plan to build a new residence hall for sixty women. After that had been completed, three more dorms would be built, including one with a “meals services division.” In the end, Tech scrapped these plans in favor of a more compact, two-phase residence hall complex.

Each section of Co-Ed Hall was designed to house 300 students. A dining facility seating all 600 would connect the two. Contractor Herman Gundlach once again took on the job, starting with the construction of “a heated tent like structure composed of scaffold rings and Vis-Queen, which enabled crews to work in relative comfort despite the severity of Northern Michigan winters.” Gradually, scaffolding gave way to masonry, and in just ten months the first phase of Co-Ed Hall was open for occupancy. Phase I–called West McNair today–stood three stories high and, like its neighbor Wads, featured a large lounge, a sizable recreation room, and an apartment for a counselor-in-residence. As in DHH, the university took pride in offering each floor of double rooms “telephone service in the corridors.” Construction on Phase II, described as a “high rise type dormitory building,” began in 1966 and wrapped up the following year. “Suite-type rooms,” noted one advertisement at the time, “with connecting baths and some single rooms are being considered.” Between the two–both physically and chronologically–was placed the cafeteria, which offered not only a dining area but another lounge, post office, telephone switchboard, and office space. Mercifully for students fighting a Copper Country winter, the plans called for enclosed corridors to take residents from each wing of Co-Ed Hall to the dining room.

What stands out for former residents, whether they called their home Co-Ed Hall or McNair? Many would point to the scenic views. While there’s no such thing as poor scenery in the Copper Country, this dorm enjoyed more than most a beautiful vista, perched as it is on what students call McNair Hill. With its expansive walls of windows, the dining hall invites students to enjoy their meals with a little Keweenaw flavor, whether ablaze in fall colors or gently cloaked in winter snow.