Craving some brain food, but not a full meal? Join us for a bite at mtu.edu/huskybites!

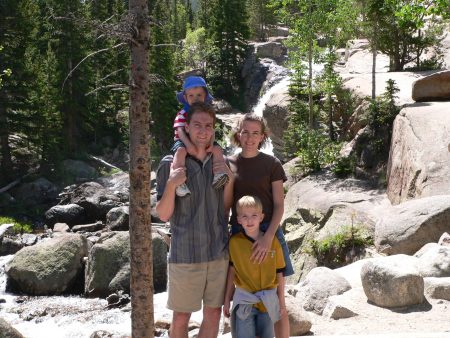

Grab some dinner with College of Engineering Dean Janet Callahan and special guests at 6 p.m. (ET) each Monday during Husky Bites, a free interactive Zoom webinar, followed by Q&A. Have some fun, and learn something new. Everyone is welcome!

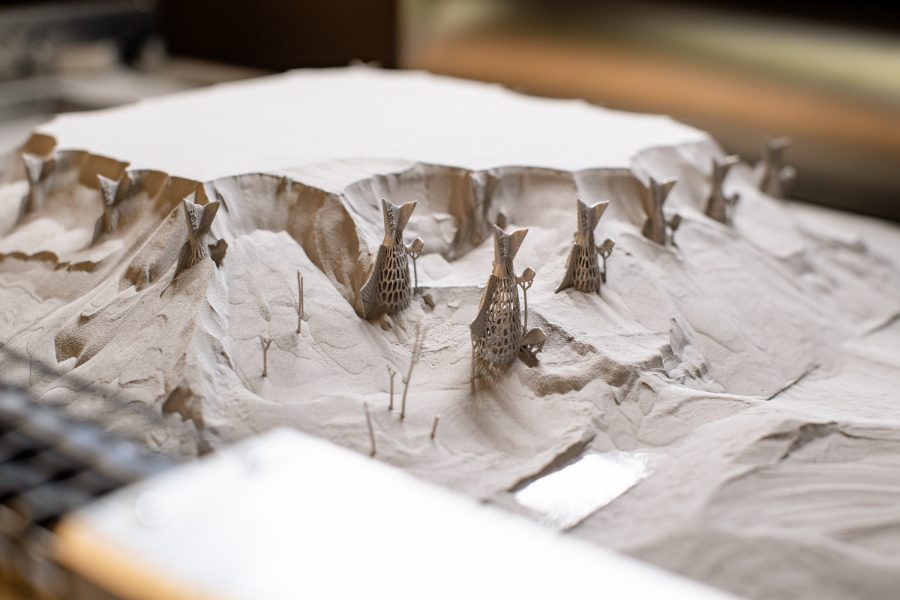

Husky Bites is a free family-friendly webinar that nourishes your mind. The Spring 2022 series kicks off this Monday (January 24) with “Winter Carnival—One Hundred Years,” presented by University Archivist and alumna Lindsay Hiltunen. From queens to cookouts, snow statues to snowballs, skating reviews to dog sled races, discover the history of Winter Carnival across the decades, through rich images of fun and festivities via the Michigan Tech Archives. Joining in will be mechanical engineering alumna Cynthia Hodges, who serves as a Wikipedian in Residence (WiR) for Michigan Tech. To celebrate the 100th anniversary, she is organizing a Winter Carnival Wikipedia Edit-a-thon, and alumni and students are welcome to help.

Check out the full Spring 2022 “menu” at mtu.edu/huskybites.

“We created Husky Bites for anyone who likes to learn, across the universe,” says Dean Callahan. “We aim to make it very interactive, with ‘quizzes’ (in Zoom that’s a multiple choice poll) during the session. Everyone is welcome, and bound to learn something new. Entire families enjoy it. We have prizes, too, for attendance.”

The series features special guests—engineering professors, students, and even some Michigan Tech alumni, who each share a mini lecture, or “bite”. During Husky Bites, special guests also weave in their own personal journey in engineering, science and more.

Have you joined us yet for Husky Bites? We’d love to hear from you. Join Husky Bites a little early on Zoom, starting at 5:45 pm, for some extra conversation. Write your comments, questions or feedback in Chat. Or stay after for the Q&A. Sometimes faculty get more than 50 questions, but they do their best to answer them all, either during the session, or after, via email.

“Grab some supper, or just flop down on your couch. This family friendly event is BYOC (Bring Your Own Curiosity).”

Get the full scoop and register at mtu.edu/huskybites. Check out past sessions, there, too. You can also catch Husky Bites on the College of Engineering Facebook page.