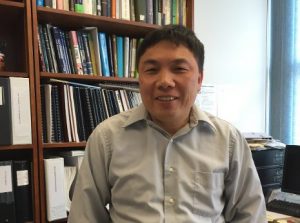

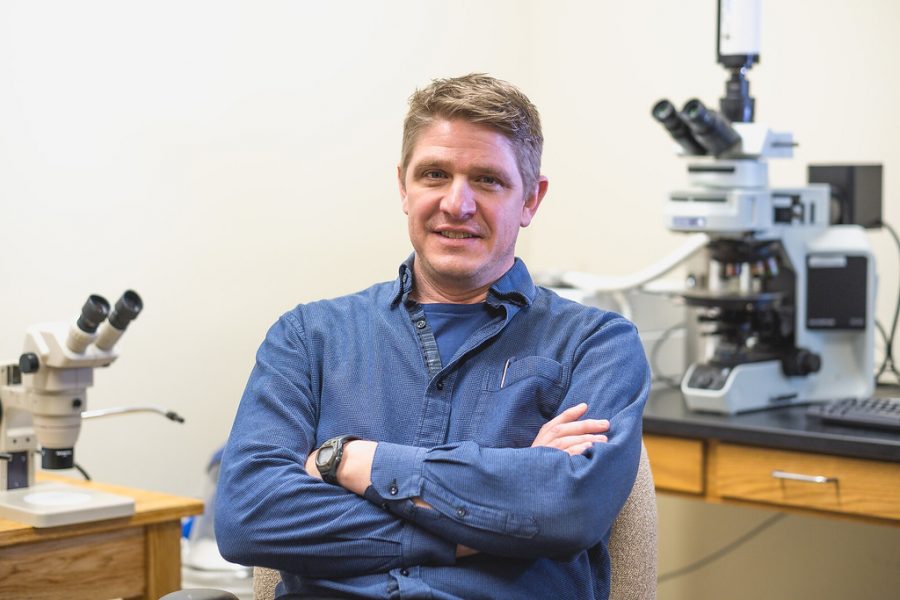

Ana Dyreson is an assistant professor of Mechanical Engineering-Engineering Mechanics at Michigan Tech. Her work centers on solar and alternative energy—and the impacts of climate change on those systems in the U.S. Great Lakes region through her Great Lakes Energy Group.

“In the last few decades, solar photovoltaics (PV) have become extremely cost-competitive,” she says. “This economic reality, combined with a push for decarbonization of the electric power sector in general, means that large-scale solar PV is growing—not only in traditional southern climates but also in the north where significant snow can reduce power output.”

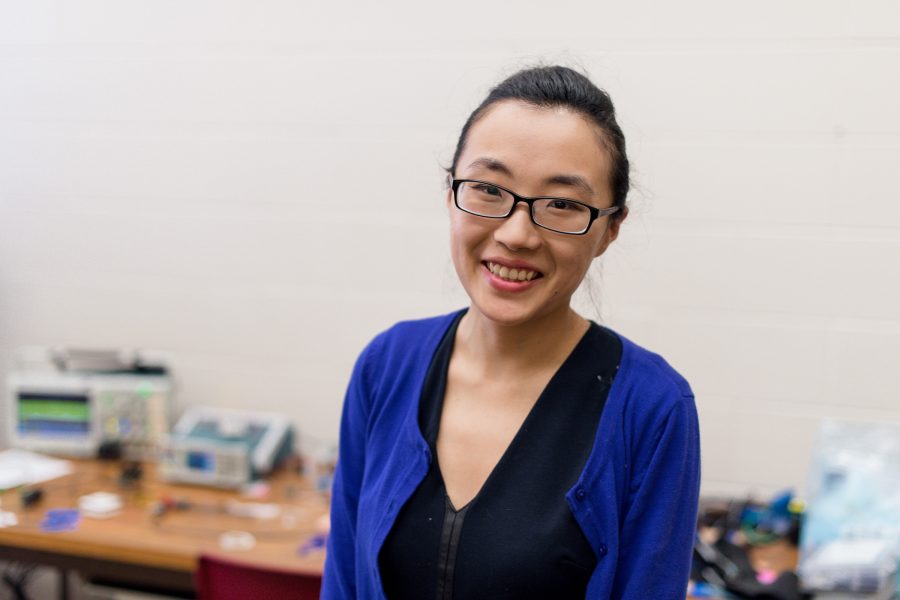

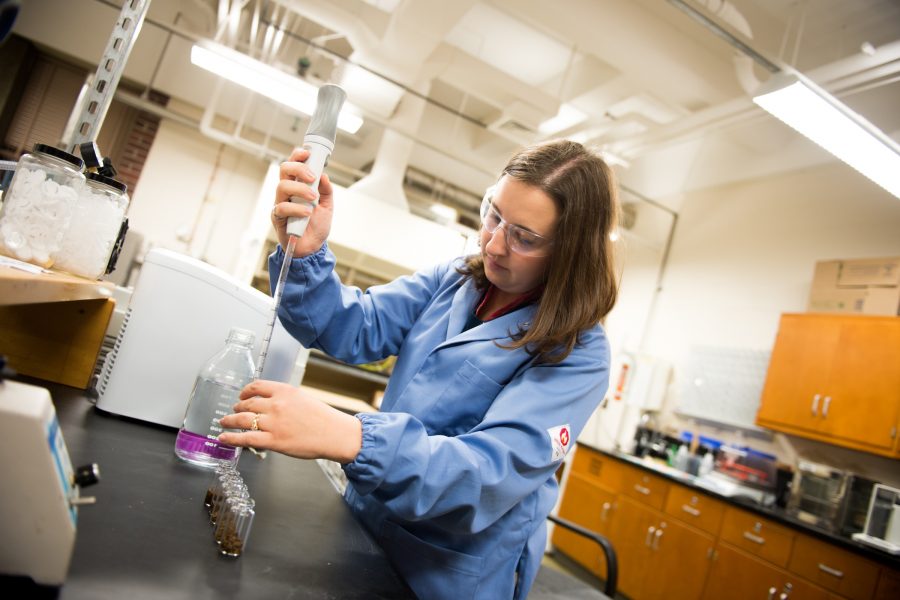

Dyreson’s students at Michigan Tech, Ayush Chutani and Shelbie Davis are both involved in doctoral research on how to better understand just how solar PV systems shed snow, in particular, single-axis tracking systems, including modeling tto explore how widespread snow events might impact future power system operations.

“We are energy engineers who work in the context of a changing environment.”

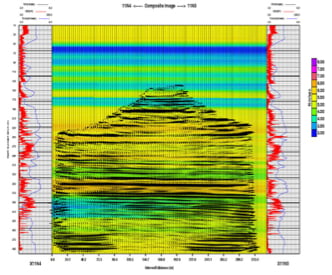

Dyreson and her team use energy analysis and grid-scale modeling to study the performance of renewable technologies.

“Our research links power plant-level thermodynamic models, climate models, hydrology models, and electricity grid operation models—all to understand how weather and climate change impact future power systems,” she explains.

In August 2022 Dyreson began conducting research at the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Energy Regional Test Center (RTC), a newly built Michigan Tech facility operated by the Advanced Power Systems Laboratory (APS LABS) at Michigan Tech. Her research on single-axis tracking systems is supported by Array Technologies, Inc., who supplied a ten-row, single-axis tracking solar system and continues to partner on research.

Under the technical oversight of Sandia National Labs, the RTC program represents a consortium of five outdoor solar research sites across the U.S. that evaluate the performance and reliability of emerging PV technologies.

The RTC program gives U.S. solar companies access to these sites and to the technical expertise of Sandia and its academic partners, to drive both product innovation and commercialization of new high-efficiency solar products.

Dyreson earned her PhD in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and her MS in Mechanical Engineering at Northern Arizona University. She conducted post-doctoral research in electricity grid modeling at the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). She earned her BS in Engineering Mechanics from University of Wisconsin–Madison. She’s a registered Professional Engineer in Wisconsin.

“I am lucky to work with talented PhD students including Ayush and Shelbie,” says Dyreson. “They each have unique professional backgrounds and personal interests in the work that they do, and it’s fun to see their work unfold.”

“Although we had never met, I sought Ana out as my faculty advisor before I even started at Michigan Tech,” says Davis. “I was fascinated by her work with alternative energy systems, specifically solar power. And Ayush has been a great PhD colleague and resource, as he is further in his PhD process and is also focusing on solar energy generation.”

Davis is earning her PhD in Mechanical Engineering from Michigan Tech remotely, while working as a laboratory manager and instructor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Saint Martin’s University in Lacey, Washington, near Olympia, the state capitol. At Michigan Tech, students can earn a PhD remotely in either Mechanical Engineering or Civil Engineering.

Chutani took part in the 26th United Nations climate change summit, COP26, in Glasgow, Scotland with the Michigan Tech delegation led by Chemistry Professor Sarah Green. Chutani traveled to Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt in 2022 to attend COP27, again with the delegation from Michigan Tech.

“Energy is something you cannot taste, see, or touch, yet it powers our lives—what magic!”

Last December, Dyreson was awarded a grant just shy of $500,000 from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for a project called “Electrification and Climate Resilience in the Rural North: Challenges and Opportunities.” She’ll be identifying social and technological challenges to resilient and equitable low-carbon electrification. That includes seeking answers on how to best electrify the energy sector, while at the same time adapting electric power systems to climate change. One primary question she plans to address: Which are the most technically feasible and socially acceptable system pathways?

Prof. Dyreson, how did you first get into engineering? What sparked your interest?

From a young age I have been interested in how society manages energy. Following one of my older sisters into engineering was an obvious way to explore this passion, and lead me to mechanical engineering and work on renewable energy and electric power systems.

Hometown, family?

I am from Portage, Wisconsin. I grew up on a south central Wisconsin farm with my parents and three sisters.

Any hobbies? Pets? What do you like to do in your spare time?

I enjoy spending time with my family, especially biking and camping together. I love to run in all weather conditions, by myself or in a group, on road or trail, for fun or for competition—I love to run!

Research note:

Dyreson’s research on single-axis tracking systems is part of a project led by Sandia National Laboratories and funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Energy Technologies office Award Number 38527.

Read more:

MTU, Sandia to Cut Ribbon on New DOE Regional Test Center for Emerging Solar Technologies

Watch:

During Husky Bites, Dr Dyreson explains the impacts of snow on high solar-share power systems of the future, from the solar module to the power grid.

Check out the full session of Dr. Ana Dyreson’s Husky Bites webinar.