By Riley Dickert, Innovative Global Solutions

Thud!

With one final toss, our last suitcase was out of the van and onto the long Kenyan grass.

The almost 10-hour journey by car was long, but nothing a Tech student wasn’t used to – at least not usually.

As we drove through herds of cattle, sheep, and goats, my mind was overwhelmed with the novelty of my surroundings. If the constant honking at livestock wasn’t enough, throw in some Baboons and Zebras, and the whole experience was straight out of a fever dream.

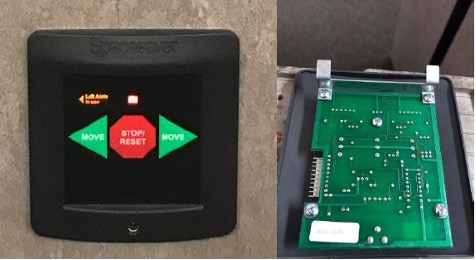

My teammate Emma and I were in Kenya to implement an aeration system our project team had developed for a local aquaponics facility. Aquaponics is a method of agriculture where fish farming (aquaculture) and soil-less plant farming (hydroponics) are combined into one recirculating system. If done correctly, the practice can use much less water and produce less waste than either of the component agriculture styles. Over the past year, we worked with staff from the aquaponics facility to learn about design constraints, develop engineering empathy, and get constant updates on facility conditions. Our two-week trip in Kenya was just the conclusion of hundreds of hours of international communication, research, and prototyping of our idea to help improve the new aquaponics facility. If everything went as planned, we could implement and test our aeration prototype.

When I first started at Michigan Tech, I came in as a physics major with my heart set on studying the universe! I realized in my third year that I had no good idea of what I really wanted to study within physics and (more importantly) that I wanted to avoid being in school for seven more years to find out. I had taken some other courses for my free electives; maybe I could pivot? What I found out the hard way is that it was difficult to find a job in engineering… especially if you weren’t an engineer. So midway through my third year, I was looking for ways to make myself more appealing as a job candidate. That’s when I stumbled upon a project that really caught my eye: an enterprise was doing a project on sustainable agriculture (I had just watched the documentary “Kiss the Ground,” which is definitely worth a watch), and I was curious to find out more. I reached out to the President of the Innovative Global Solutions (IGS) Enterprise and went to the first project meeting I was invited to. I didn’t know what enterprise was all about, but I needed experience, which seemed like an exciting way to get it.

Despite our best efforts to stay up to date with the project site in Kenya, there was some information our sponsor hadn’t known. The facility manager had been offsite, and the facility had been critically vandalized in the week leading up to our visit. The fish in the pond (the life force of the system) had been taken, the pump that brings water to the crops was stolen, the plants had died, and the electrical systems had been scavenged. Given the facility’s status, our two-week trip dedicated to testing our prototype looked impossible. We would unlikely have even one day to test our prototype, much less two weeks. Unfortunately, sometimes things don’t always go as planned.

Starting with the IGS enterprise in my fourth year as a Physics major and taking over the reins of project lead meant many novel responsibilities were put on my plate. Luckily for me, the past lead was really supportive. During the summer, I was told we would need regular sponsorship meetings to learn about project expectations, site conditions, and the team in Kenya we would be working with. Then, when it got a bit closer to the school year, I was told that I needed to make something called a ‘Gantt Chart’ and plan the entire semester out. The first couple of meetings were time-consuming to prepare for but went great. Despite not being an engineering major, I was starting to feel like this was a space in which I could gain some valuable skills. The only problem was that this project was complicated – many moving parts, open-ended questions, and timelines. It didn’t take long before I felt overwhelmed by how many things I had to get done for my first ‘real-world project.’

Preventing further vandalism, repairing the facility, and testing our prototype was a really intimidating list to check off in two weeks – our testing was initially planned to take up the whole two weeks alone. After seeing the site conditions firsthand, I could tell that making this all work would be a big stretch. But at the same time, what else could we do but try to make the impossible happen?

When the responsibilities of being a project lead first hit, my initial reaction was to back away. I had always been a pretty good student, but when it came to project work, I felt like I had a knack for getting lost in the big picture and psyching myself out.

Instead of giving up, I did my best to figure out how to lead an effective team. Not being too hands-on while not being too hands-off. Holding team members accountable while remembering we’re all busy people. Being in charge… is surprisingly tricky. But I started to learn that often the most significant barrier to success was my own head. It seems like it’s much easier to solve big problems when you break them down into smaller pieces. Kind of like when you want to solve for the area under a curve (which looks pretty tricky), you break it down into infinitely small components and then summate over the bounds and… yeah… calculus.

So, to solve our big problem, we took it one step at a time.

First, we needed to figure out how to solve the vandalism problem. We learned that many issues could be solved by always having someone on-site and creating a sense of community ownership of the project. We worked with village leaders to set up a community day where we could talk with locals about what the facility was there for and how it could improve their access to food. We needed to incentivize neighbors of the facility to prevent any damaging activity from going unnoticed and to have them work as the first defense against vandals.

Second, while local leaders worked to set up the community day, my teammate and I worked with our sponsor and the site staff to repair the facility. Over the next few days, we gained an intricate understanding of how business and contracting in Kenya function and worked alongside local contractors to repair the facility and build some new additions. Every day, we met with our site team to discuss the work to be done that day and where we were in the process. We headed out around 8 am and got home around 9 pm every night. The days were so long and full of new experiences that sometimes it was hard to remember what day it was. To keep me busy during our 3-4 hours of daily driving, I wrote down ideas and journaled about our experiences.

Finally, after a little over a week of work, we had made some significant progress: the site’s essential components were back online, a fence had been built around the fishpond, a dwelling had been built for a full-time resident at the facility, and new seeds were planted in the greenhouse. On our last day at the site, the stage was set. We got ready to test our prototype in the system. Unfortunately, it was during that last day when we finally did the thing we had planned the longest for that we had both the most go wrong, and the most go right simultaneously. The pump was not pulling water properly, adjustments for the international electric grid were not looking right, and a major structural issue in the prototype made success look unattainable yet again. Our team didn’t have access to many of the traditional tools and supplies we needed to make everything work, but we did have a new network of local tradesmen and contractors that we had been working with for the past couple of weeks. Through our combined efforts, we worked through the prototype’s issues and got our system up and running in just one day.

There are times when approaching big problems and projects will be intimidating – there’s just no way around that. But the best way to get good at approaching big problems is through experience in doing so. Being a project lead, going to Kenya, and becoming President of an enterprise are experiences I never could have imagined myself having even two years ago.

The time I got to test out leading a project and an enterprise not only gave me good experience but also helped me gain a better understanding of what I wanted to do. After being a leader for the past year and a half, I realized that I want to be a project manager or high-level decision-maker, specifically for teams that solve big complicated problems. Without my time in the program, I genuinely don’t know where my future would be aimed. I guess that’s just how life goes – the river doesn’t always take you where you think it will. As long as you’re willing to try new things and follow what interests you, eventually, the path forward might just hit you head-on.

Thud!