By Laura Fiss

Anne Fadiman says that there are two kinds of book-lovers: “courtly” and “carnal.” They differ in their attitudes toward the marks and side-effects of reading: creases, dog-eared pages, bent or broken spines, ripped pages, food and water stains. Courtly lovers treat the book with respect and veneration, honoring the book as object. Carnal lovers consume the book enthusiastically, viewing any degradation of the object as a natural result of a delightful encounter. I fall somewhere in the middle, as I suspect most of us do. I treat my books with care – particularly the nineteenth- and twentieth-century volumes in my possession – but I also see the creased spines of some of my more well-loved paperbacks as a badge of honor. The only time I wrote in a library book (gasp!), it was a copy of H. J. Jackson’s Marginalia, and I carefully initialed and dated my notation.

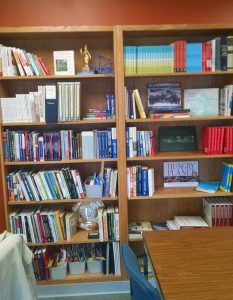

The child of bibliophiles, I feel a strong attraction to the book as object. My childhood bedroom, a wood-paneled former study, had one wall of bookshelves and another of windows. I feel a strong sense of comfort when I’m ensconced in a place with nearly-ceiling-high, full bookshelves. Yet as I sit in my new PHC office (with a beautiful view of the fall foliage out the window — come visit us if you haven’t already!), the bookshelf next to me doesn’t have the same effect as the bookshelves of similar height in my office in Walker (come visit there, too!). When I first drafted this post, I thought these books belonged to my office-mate, but I’ve since discovered that they consist the PHC library, which actually changes the way I think about them. At first, I thought that while titles such as The Innovation Killer and multiple copies of Business Model Generation are intriguing and the colorful, mainly paperback spines are aesthetically pleasing, nevertheless these books are, to me, as yet, only objects. Initially, I saw in them the arrangement of another single personality, one who would place Out of Poverty by Paul Polak next to The Seven Layers of Integrity by George P. Jones and June Ferrill for alphabet-defying reasons that make perfect sense to a mind not my own. Now that I know these books are for everyone, I feel less closed-off from them, knowing I could pick one up at any time and begin reading (I suppose I’m too courtly to borrow someone else’s books without their permission).

The child of bibliophiles, I feel a strong attraction to the book as object. My childhood bedroom, a wood-paneled former study, had one wall of bookshelves and another of windows. I feel a strong sense of comfort when I’m ensconced in a place with nearly-ceiling-high, full bookshelves. Yet as I sit in my new PHC office (with a beautiful view of the fall foliage out the window — come visit us if you haven’t already!), the bookshelf next to me doesn’t have the same effect as the bookshelves of similar height in my office in Walker (come visit there, too!). When I first drafted this post, I thought these books belonged to my office-mate, but I’ve since discovered that they consist the PHC library, which actually changes the way I think about them. At first, I thought that while titles such as The Innovation Killer and multiple copies of Business Model Generation are intriguing and the colorful, mainly paperback spines are aesthetically pleasing, nevertheless these books are, to me, as yet, only objects. Initially, I saw in them the arrangement of another single personality, one who would place Out of Poverty by Paul Polak next to The Seven Layers of Integrity by George P. Jones and June Ferrill for alphabet-defying reasons that make perfect sense to a mind not my own. Now that I know these books are for everyone, I feel less closed-off from them, knowing I could pick one up at any time and begin reading (I suppose I’m too courtly to borrow someone else’s books without their permission).

Still, these books don’t have the same effect as the ones in my Walker office, particularly my nineteenth-century bookcase (alphabetized by author, then with books ordered by date of publication). There’s my shelf of Jerome K. Jerome, where a few sad print-on-demand titles rub alongside first editions (British and American) purchased for a song online: few people want Second Thoughts of an Idle Fellow as much as I. Above and below lie ranks of black Penguins and white Oxford World’s Classics, slim volumes and doorstoppers with variously creased spines. Particular books remind me not only of the plot but of a moment in my personal and academic life. Little Dorrit changed my mind about Dickens. I finished The Mill on the Floss on a bus in France, tears running down my cheeks. He Knew He Was Right fired up my blood throughout its agonizing, painful, infuriating 900 pages, and I finished it while walking to my graduate seminar. While I’m no stranger to multitasking while reading – in high school I played the flute while reading Mercedes Lackey and knitting got me few several Dickens biographies in the final year of my dissertation – walking while reading has always been a matter of necessity rather than pleasure.

I relish the different traditions of reading I participate in, the different rituals of reading I’ve learned. My parents taught me to “break in” a book, particularly a large textbook, by placing it spine-down on a firm surface and gently creasing pages down from both ends. I’ve done that with several Complete Works of Shakespeare over the years. As a child and young adult, I loved filling up a canvas bag at the public library, and now I do the same thing at Portage Lake District Library with my toddler (who’s very into the Llama Llama books at the moment). As a Jew I engage in rituals of reading around prayer books and scrolls, relishing the moment when a manuscript scroll is lifted above our heads (by a web developer the other week) as we sing triumphantly and hope it stays aloft.

I’ve dedicated my life not only to the practice of reading but to the study of reading practices because the act of reading fascinates me in its potency and its fragility. We invest books and other text-carriers (next time, maybe we’ll talk about our relationships to phones) with all these properties, but at the end of the day, they’re just objects: paper, wood, rag, cloth. In the words of one of my favorite jokes (about a pool table), if it falls from a tree, it’ll kill you.

Why do we do these things? Why do we have rituals around reading, and why do some of us feel so strongly about books and the way they are treated that we might, like the chambermaid in Fadiman’s essay, tell each other, “You must never do that to a book”? Reading is many things: frustrating and fun, arduous and ardent. It can stretch time or make it fly by, make us incredibly conscious of our surroundings or transport us, in Emily Dickinson’s words, “Lands away.” The closed book is itself a metaphor for things we don’t — yet? — know. The books in my office might be closed to me at the moment, but the very fact that they’re books makes me feel at home.